The year was 1949 and the first unified central government for forty years was in power in China. Christian believers were fearful.

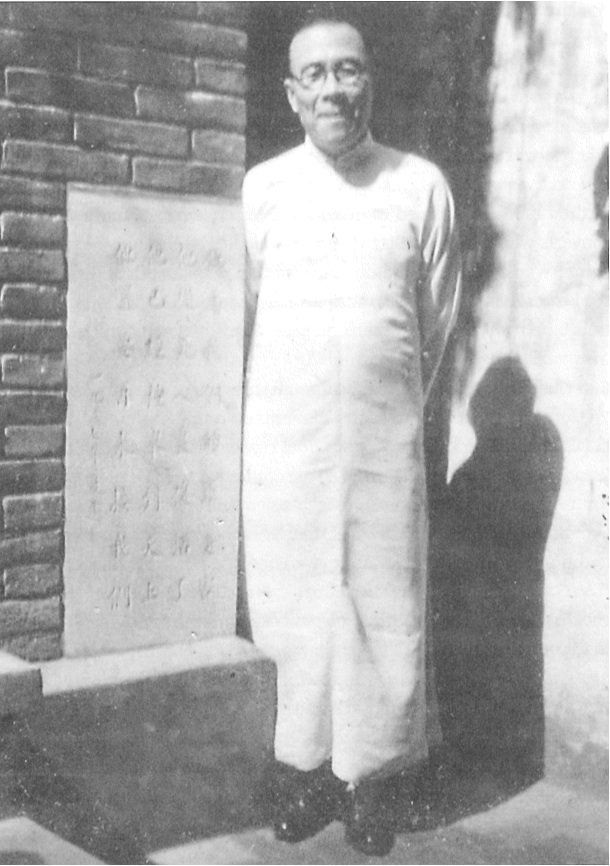

At the Peking (Beijing) Christian Tabernacle, the congregation prepared itself for Communist rule. Wang Ming Dao, the pastor, continued to hold tenaciously to Scripture. The Christian, he affirmed, should obey the authorities (Romans 13:1-7). But if ordered to go against God’s inspired Word, the Bible, then it was God’s Word that must be observed.

The ‘Three Self’ Movement

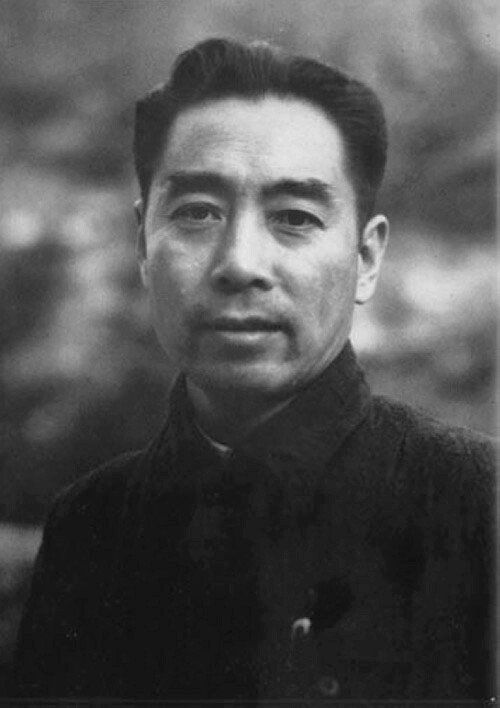

Wang Ming Dao knew the greatest threat that confronted the church would come from within. A man called Wu Yaozong, a little known YMCA secretary having strong sympathies with Communism, seized his opportunity.

Over the years many had recognised a prophetic ring in Wang Ming Dao’s words. ‘From a man with a selfish heart’, he had written, ‘any terrible act can emerge. Anyone looking for selfish gain can lie, cheat, practise evil and plot for his self interest. The majority of sins in this world issue from people who are out for selfish gain’.

Wu Yaozong approached Zhou Enlai, the Chinese premier. With his and Mao-Tse Tung’s full support, Wu drew up a ‘Christian Manifesto’. This called for the church to sever all ties with Western imperialism and purge itself of everything connected with it. The church must be self-governing, self-supporting and self-propagating. Thus was born the government-sponsored Three Self Patriotic movement (‘TSPM’), and hundreds of thousands of Christians throughout China gave it their support. Wu Yaozong rose rapidly to power.

Adverse effects

Wang Ming Dao firmly believed in the separation of church and state. He recognised that the aim of the movement was to bring the church under state control.

Besides, the Christian Tabernacle had always been independent of Western aid or connection. There was no need for Wang to join. All his deepest convictions were in conflict with the beliefs propagated by Wu Yaozong and other leaders in the TSPM. Wu wrote in an article: ‘The incarnation, the virgin birth, resurrection, Trinity, last judgement, Second Coming etc., these are irrational and mysterious beliefs which cannot be understood or explained … no matter how hard I try, I cannot accept such beliefs’. Wang Ming Dao steadfastly refused to join the TSPM. He could act in no other way.

Meanwhile the churches that had joined the movement began to feel its adverse effects. The formidable ‘accusation meetings’, already a feature of the Communist secular world were introduced into the church. Pastors who had been linked with foreign missions were isolated, and their congregations encouraged to denounce them.

Another gospel

All over China, churches were torn apart. The Peking Christian Tabernacle was like an oasis in a spiritual desert, where pure biblical gospel preaching could still be heard.

Wang Ming Dao laboured night and day, setting up his own printing press to continue publication of the Spiritual Food Quarterly. His uncompromising stand on biblical truth strengthened Christians throughout the land.

Between 1951 and 1954, he published many books proclaiming the gospel and speaking out against the modernists. Those who preach the ‘social gospel’, he pointed out, ignore the essential atoning work of Christ for the individual’s eternal salvation and the purifying effect it has in this life. They seek to transform society and establish the ‘kingdom of heaven’ in this world.

But this, taught Wang, was ‘another gospel’ (Galatians 1:9). Such people have never put their own trust in Jesus. Men and women need to know the true gospel for their eternal safety and blessing.

Alarm bells

The TSPM ground its teeth. Its leaders deeply resented the man who was ‘an iron pillar against which the whole land could not prevail’. All they could do was to mount a personal attack on Wang.

In 1954 the TSPM ordered all churches in Beijing to send delegates to an ‘accusation meeting’ against Wang Ming Dao. Leslie Lyall (OMF) writes, ‘it would be difficult to find fault with him, for he practised what he preached: upright, disciplined living’.

Throughout the meeting, Wang did not speak a word. Imprisonment or the death sentence were called for. The congregation sat silent. Many wept. No penalty could be imposed.

So Ming Dao continued to preach. The crowds were larger than ever. The evangelistic meetings in January 1955, says Leslie Lyall, ‘were probably the most fruitful he had ever conducted’.

Then students, as students will, daringly started their ‘Oppose the persecution of Wang Ming Dao’ campaign. It received wide support all over China. Alarm bells began to ring in high places. Their plan to subjugate the church to Communist control was under threat.

Accusation meetings were arranged against Wang Ming Dao across the whole of China. Nevertheless, in two weeks of meetings in the Christian Tabernacle in July 1955, attendance broke all records. Wang’s important article, We, because of Faith, had been published. With powerful logic, he dealt with the arguments of the modernists. He explained how they overturned the Bible and the Christ of the Bible. Was he being uncharitable, he asked, if he called them ‘the party of unbelievers’?

Imprisoned

The Three-Self controlled magazine (the Tianfeng) branded Wang Ming Dao ‘a criminal of the Chinese people, a criminal in the church and a criminal in history’.

On 7 August 1955, Wang preached his last sermon in the church. For thirty years he had laboured tirelessly to show his country where her true hope lay, namely, in the atoning work of Christ and obedience to his Word. His final sermon showed that the TSPM church leaders had betrayed Christ in China.

At midnight the police arrived and Wang was thrown into prison without a conviction. He was parted from his wife and did not realise that she had been imprisoned too.

To the Communists, Wang Ming Dao’s refusal to join the TSPM was a counter-revolutionary act, the very worst of crimes. They could not, of course, understand that he was called by God to summon the church to chastity to Christ.

Wang shared a filthy cell with two other prisoners. From his daily interrogations, Wang was returned to his cell to be taunted with descriptions of torture reserved for preachers, and to be beaten and pressurised by his fellow prisoners to confess his ‘crimes’.

Freedom and rearrest

The authorities used every device to break down the resistance of this powerful opponent to their scheme. After a year of tremendous pressure, Wang was informed of a wave of arrests of Bible-believing Christians sympathetic to him. Then news came of Jing Wun’s plight. She, too, was in detention, unable to eat the coarse prison food because of her poor health. China’s ‘iron man’ began to weaken. He ‘confessed’ to crimes he had not committed, and agreed to join the TSPM and preach for them. He signed a document stating he was a counter-revolutionary, and he and Jing Wun were freed.

Then began the darkest six months in Wang Ming Dao’s life. The TSPM leaders were elated. They waited eagerly to claim the lifeless jewel that would crown their movement. But with a mind deranged with guilt and sorrow for the denial of his Lord, Wang never did join or preach for the TSPM. With the same tender love the Lord had shown to Peter, Wang was granted time to regain normality by a period of illness.

He informed the government he could not join, Jing Wun affording outstanding support to her husband. Exactly seven months after their release, Wang Ming Dao and Jing Wun were re-arrested.

Restored in spirit

By the 1960s, Mao Tse Tung’s disastrous policies, along with natural calamities, left millions starving in a terrible famine. All, except high government officers, were affected. Officials at the bottom level were blamed for Mao’s mistakes.

While some ‘counter-revolutionaries’ were released at this time, Wang Ming Dao received the sentence he most dreaded — life imprisonment. Earlier, the Beijing People’s Court had drawn up charges against him. The recorded evidence stated that Wang Ming Dao and his wife had undermined the TSPM set up by Chinese Christians, and had accused the TSPM of committing adultery with the world.

It was now that God met with Wang Ming Dao and restored him to his brightest hour. A scripture he had learned many years before was brought by the Holy Spirit to his remembrance: ‘When I fall I shall arise, when I sit in darkness the Lord will be a light unto me. I will bear the indignation of the Lord because I have sinned against him until he pleads my cause and executes judgement for me’ (Micah 7:7).

One great prison

Through the next sixteen and a half years Ming Dao was to suffer solitary confinement, torture, and the horror of five months of daily meetings attempting to force confessions from him.

But the Lord stood by him and gave him the victory through his Word. Never again was he to fall. Though Wang Dao’s voice was silenced, his life still spoke throughout the land.

During this time all China had become one great prison from which there was no escape. The ‘little red book’ of Mao’s teachings was in everyone’s hands. As the Cultural Revolution flourished, everyone spied on his neighbour and almost every family suffered at least one death.

Preaching again

In Beijing, more than anywhere else, the youthful Red Guards were authorised to terrorise intellectuals. Had Wang Ming Dao still been there, he would have been targeted for death. The ancient city walls were demolished, as things old and beautiful were destroyed to make way for Mao’s new China. Even the TSPM ceased to function.

Gradually it became clear that Mao had failed the nation. His ‘little red book’ was laid aside. God had destroyed the wisdom of the wise (1 Corinthians 1:19). In 1976 Mao Tse Tung died, and his revolution died with him.

Prison doors opened, and seventy-nine-year-old Wang Ming Dao, now nearly blind and very deaf, was free again. In his little home in Shanghai, and always mindful of his fall, he began again to preach the Holy Scriptures which are able to make one ‘wise unto salvation’ (2 Timothy 3:15). He died in 1991, a radiant witness to his Saviour.

The healthy state of the vast house-church movement in China today, and the breathtaking increase of true Bible-believing Christians there, are not unrelated to the life and work of Wang Ming Dao. He has emerged as the greatest Chinese Christian leader of the twentieth century.