On 19 May Iain Murray was asked to address the annual Grace baptist assembly on the subject of C.H.Spurgeon and his battle with hyper-Calvinism’. It is not that this group of 1689 Confessionalists are drifting in that direction, indeed a better grasp of experiential Calvinism would lift us all – pulpits and churches. But, as lain Murray pointed out, whenever Calvinism is revived, hyper-Calvinism appears. Conversely, when Calvinism is eclipsed then hyper-Calvinism is a spent force.

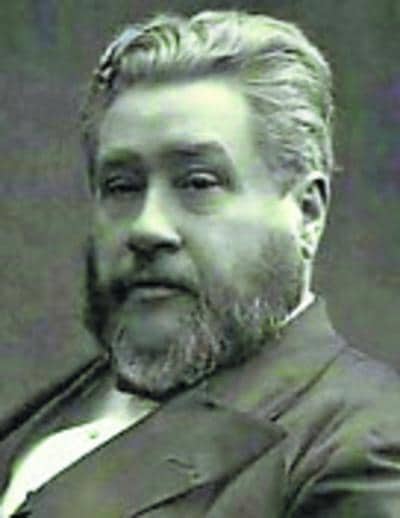

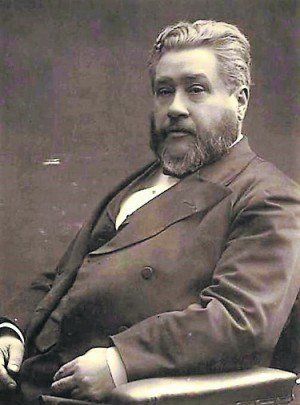

One of Charles Haddon Spurgeon’s first battles was with hyper Calvinism. The popular biographies, such as those of Fullerton and Drummond, do not touch on this, judging it to be ‘some difference in finer theological points’. In the autobiography Spurgeon considered it important. This attack began in January 1855 when the twenty-year-old Spurgeon had been a preacher for nine months at the New Park Street congregation, one of 1,400 Particular Baptist churches in England.

Spurgeon’s opponent was fifty-one-year old James Wells, referred to by Spurgeon as ‘King James’, and by the press as ‘Wheelbarrow Wells’ (perhaps he had started life selling produce, and before graduating to a horse and cart had used a wheelbarrow in the London streets). He was a1so dubbed the ‘Borough Gunner’ because of the artillery which came from his chapel and pulpit in Surrey Tabernacle, Borough High Street.

Spurgeon’s defender

Charles Waters Banks was a very different personality who also became drawn into this controversy. He was a meek and forbearing individual as well as being extremely industrious. In 1854 Banks caught cholera. As he recuperated from his illness he went to visit his friend Spurgeon and the two men prayed together. It was an unforgettable experience-‘What a Patmos,’ remarked Spurgeon.

Banks busied himself by travelling extensively to preach. He was for forty-three years the editor of the Earthen Vessel, in addition editing Cheering Words for thirty-six years, as well as editing the Christian Cabinet. He died in 1886, until the last sitting up in his bed, pen and papers at hand.

In the Earthen Vessel of December 1854 Banks wrote of visits he had made to New Park Street and of the benefit he had received from hearing young Spurgeon. The following month an anonymous article appeared from a certain ‘JOB’, but evidently from James Wells, in which he argued that Spurgeon’s ministry was dangerous: ‘Beware of a mock and arrogant humility, of the soft raiment of refined and studied courtesy and fascinating smile … Also I have -most solemnly have- my doubts as to the Divine reality of his conversion … Concerning Mr Spurgeon’s ministry, I believe that it is most awfully deceptive…’

Why the clash?

What was the cause of this clash? It was not one of personalities, the old preacher and the young, with the editor caught in the middle. Nor was it the elder preacher’s jealousy at the younger’s popularity which brought about this antagonism, although this was promoted by the popular newspapers. Spurgeon esteemed Wells.

The real explanation, Iain Murray showed, was that Wells sincerely believed that the Calvinistic tradition he represented was the purest form of Christianity, and for anyone to question it would be heresy. If men were actually to be summoned to believe in Christ, to Wells was ‘Fullerism’ and Wells saw it as his calling to ‘knock down duty faith’.

Should the Earthen Vessel support Spurgeon’s views it would be a ‘disastrous change of direction’, said Wells. Banks responded that he was not frightened by Wells’ veiled threat. He felt that ‘God had put Spurgeon on the walls of Jerusalem for usefulness.’ And in his subsequent visits to the New Park Street Chapel, Banks reported favourably on Spurgeon: ‘There are some contradictions, but God has raised him up as a true evangelist to win souls over to Jesus Christ.’ This, coming from a preacher who himself did not believe in the duty of all men to believe in Christ, was very important. Every instinct in Banks persuaded him God had sent Spurgeon.

Another turn in the controversy, Iain Murray indicated, was when a young man called T. W. Medhurst, a member in James Wells’ congregation, crept guiltily into the Maze Pond Chapel early in 1854 to hear Spurgeon-whom he had been taught to consider ‘a mere Arminian’. After a period of soul-distress he was converted through a Thursday night sermon at New Park Street and began, soon after, to preach in the streets. He became the first student in Spurgeon’s college.

Medhurst, in an attempt to placate the antagonists, entered the controversy in the pages of the Earthen Vessel: ‘Duty faith? What is it? Examine it-“Believe and be saved. Believe not and be damned.” It is like Mark 16:16.’

The errors of hyper-Calvinism

Charles Haddon Spurgeon pointed out four fundamental errors in hyper-Calvinism.

1. The hyper-Calvinist denies that gospel invitations are to be delivered to all people without exception.

He limits the purpose of gospel preaching to bringing in the elect, and so only the elect are to be addressed with the commands, invitations and offers of the Word. There is to be no pleading with, exhorting and beseeching of an entire congregation of sinners.

That attitude was totally rejected by Spurgeon, who on many occasions addressed every single hearer thus: “‘These are written that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing ye might have life through his name.” Look to him, blind eyes; look to him, dead souls; look to him. Say not that you cannot; he in whose power I speak will work a miracle while yet you hear the command, and blind eyes shall see, and dead hearts shall spring into eternal life by his Spirit’s effectual working’ (MTP, 40, 1894, p.502).

2. The hyper-Calvinist declares that the warrant a sinner has to come to Jesus Christ is found in his own experience of conviction and assurance.

That warrant, the hyper says, cannot be obtained until we are inwardly spiritually exercised. But Spurgeon preached that all mankind has a warrant to believe extended to them, giving them the right to place their trust in the Lord Jesus. That warrant is the universal command found in the Word of God that all men should repent of their sins and should believe on the Lord Jesus. ‘Do not wait for your feelings to convince you that you can venture on Christ,’ urged Spurgeon, ‘you have the right to come just as you are today because God is sincerely beseeching you to come to his Son for pardon.’

In his 1863 sermon on the ‘Warrant of Faith‘ Spurgeon tells people that if the warrant were not in the Word of God but in the sinner’s own condition the result has to be that people would be driven to look within themselves and ask, ‘Have I sufficiently broken my heart?’ rather than looking to a welcoming Saviour (MTP, Vol.9, p.529ff). And that exactly is the case today. Spurgeon pointed out pertinently that those whose hearts are most broken feel most the obdurate hardness of their hearts.

3. The hyper-Calvinist declares that human inability means man cannot be urged to come at that moment to Christ.

A universal command must presuppose a modicum of ability, he says. Spurgeon replied that he would not tone down man’s depravity and helplessness one whit. The gospel is one of grace and therefore rests upon despair of human resources and potency. It is only on the presupposition of total depravity and complete human impotence that the full glory and power of the gospel can be declared. Spurgeon then would exalt God’s power to save.

There are two lines found in Scripture, one that declares man’s helplessness through being dead in sin and yet that he is responsible to turn to God, and the other, that the Lord is sovereign to save. As John Duncan said, the idea that God did half and man did half is utterly false. God doing all and man also doing all is the teaching of the Bible.

4. The hyper-Calvinist denies the universal love of God.

He has a fearful caricature of the real nature of God which would present him as fierce, and not easily induced to love. If we fellowshipped more with Christ, said Iain Murray, we would know and love him more. Then there would be no uncertainty that God desired the salvation of sinners. ‘How oft would I have gathered you,’ says the Saviour to recalcitrant Jerusalem.

Conclusions

Iain Murray’s conclusions were fourfold.

1. Any true biblical theology is not exclusive. The Bible’s teaching on a divine election of grace is not intended to divide Christian from Christian but Christian from the world. Spurgeon said that he knew of many who were savingly called who did not themselves believe in divine calling, and that many went on to the end who did not believe in the perseverance of the saints. They hold to such errors of judgement, and yet we meet with them and every believer around the cross. Spurgeon hated separateness.

2. There is a danger that biblical truths are not presented in the right order. In the final edition of Calvin’s Institutes teaching on divine election follows teaching on justification. In evangelism election is not placed in a position of priority. It is free justification through Christ which is central.

3. When Calvinism ceases to be evangelistic it is a cerebral, chilling and unattractive religious system. It was when Carey went to India and Fuller led the missionary interest in England that a change in the Baptists came about and they began to grow.

4. Iain Murray’s conclusion was to point out-what a wonderful thing it was that Spurgeon at twenty years of age did not become a hyper-Calvinist. If he had then this talk to the Grace Assembly would not have taken place, and his sermons would not be read all over the world, as they are, even today.