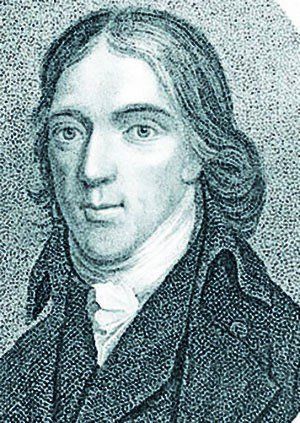

In this short series on the spirituality of Samuel Pearce (1766-1799) we have been reflecting on his passion for the salvation of his fellow human beings.

Given his ardour for the advance of the gospel, it is only to be expected that Pearce would be vitally involved in the formation, in October 1792, of what would become the Baptist Missionary Society, the womb of the modern missionary movement.

In fact, by 1794 Pearce was so deeply gripped by the cause of missions that he was convinced that he should offer his services to the society and go to India.

There he planned to join the first missionary team the society had sent out, namely, William Carey (1761-1834) and John Thomas (1757-1801). He began to study Bengali on his own.

Preceding the meeting of the society’s administrative committee at which Pearce’s offer would be evaluated, Pearce set apart ‘one day in every week to secret prayer and fasting’ for direction during the month of October 1794.

He also kept a diary of his experiences during this period, much of which Andrew Fuller (1754-1815) later inserted verbatim into his Memoirs of Pearce and which admirably displays what Fuller called his friend’s ‘singular submissiveness to the will of God’.

Dullness

During one of these days of prayer, fasting, and seeking God’s face, Pearce recorded how God met with him in a remarkable way.

He had begun the day with ‘solemn prayer for the assistance of the Holy Spirit’ so that he might ‘enjoy the spirit and power of prayer’, have his ‘personal religion improved’, and his ‘public steps directed’.

He proceeded to read a portion of Jonathan Edwards’ life of the American missionary David Brainerd (1718-1747), a book that quickened the zeal of many of Pearce’s generation, and to peruse 2 Corinthians 2-6.

Afterwards he went to prayer but (he recorded) his heart was hard and ‘all was dullness’. He feared that somehow he had offended God.

Suddenly, Pearce wrote: ‘it pleased God to smite the rock with the rod of his Spirit, and immediately the waters began to flow’.

A meeting with God

Likening the frame of his heart to the rock in the desert, which Moses struck to bring forth water (Exodus 17:1-6), Pearce found himself unable to generate any warmth for God and his dear cause. Only God, by his Spirit, could ‘touch’ Pearce’s heart and quicken his affections.

Suddenly, he tells us, he was overwhelmed by ‘a heavenly glorious melting power’. He saw afresh ‘the love of a crucified Redeemer’ and ‘the attractions of his cross’.

He felt ‘like Mary [Magdalene] at the master’s feet weeping, for tenderness of soul; like a little child, for submission to my heavenly father’s will’.

The need to take the gospel to those who had never heard it gripped him anew, he wrote, ‘with an irresistible drawing of soul’ and ‘compelled me to vow that I would, by his leave, serve him among the heathen’.

As he wrote later in his diary: ‘If ever in my life I knew any thing of the influences of the Holy Spirit, I did at this time. I was swallowed up in God. Hunger, fulness, cold, heat, friends and enemies, all seemed nothing before God.

‘I was in a new world. All was delightful; for Christ was all, and in all. Many times I concluded prayer, but when rising from my knees, communion with God was so desirable, that I was sweetly drawn to it again and again, till my … strength was almost exhausted.’

Christ’s will his own

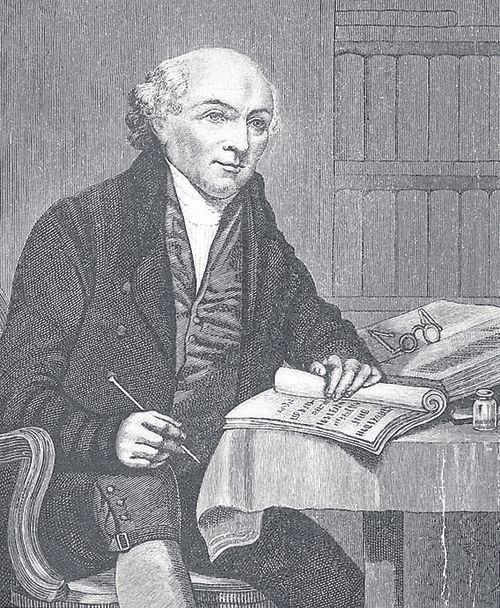

The decision of the society as to Pearce’s status was ultimately a negative one. When the executive committee met at Roade, Northamptonshire, on 12 November 1794, it was of the opinion that Pearce could best serve the cause of missions at home in England.

Pearce’s response to this decision is best seen in extracts from two letters. The first, written to his wife Sarah the day after he received the decision, stated: ‘I am disappointed, but not dismayed. I ever wish to make my Saviour’s will my own’.

The second, sent to William Carey over four months later, expressed a similar desire to submit to the perfectly good and sovereign will of God.

‘Instead of a letter, you perhaps expected to have seen the writer; and had the will of God been so, he would by this time have been on his way to Mudnabatty: but it is not in man that walketh to direct his steps.

‘Full of hope and expectation as I was, when I wrote you last, that I should be honoured with a mission to the poor heathen, and be an instrument of establishing the empire of my dear Lord in India, I must submit now to stand still, and see the salvation of God.’

The will of God

Pearce then told Carey some of the details of the November meeting at which the society executive made their decision regarding his going overseas.

‘I shall ever love my dear brethren the more for the tenderness with which they treated me, and the solemn prayer they repeatedly put up to God for me.

‘At last, I withdrew for them to decide, and whilst I was apart from them, and engaged in prayer for divine direction, I felt all anxiety forsake me, and an entire resignation of will to the will of God, be it what it would, together with a satisfaction that so much praying breath would not be lost; but that He who hath promised to be found of all that seek him, would assuredly direct the hearts of my brethren to that which was most pleasing to himself, and most suitable to the interests of his kingdom in the world.

‘Between two and three hours were they deliberating, after which time a paper was put into my hands, of which the following is a copy.

‘The brethren at this meeting are fully satisfied of the fitness of brother P[earce]’s qualifications, and greatly approve of the disinterestedness of his motives and the ardour of his mind.

‘But another Missionary not having been requested, and not being in our view immediately necessary, and brother P[earce] occupying already a post very important to the prosperity of the Mission itself, we are unanimously of opinion that at present, however, he should continue in the situation which he now occupies.’

Response

In response to this decision, which dashed some of Pearce’s deepest longings, he was (he said) ‘enabled cheerfully to reply: “The will of the Lord be done” and receiving this answer as the voice of God, I have, for the most part, been easy since, though not without occasional pantings of spirit after the publishing of the gospel to the Pagans’.

From the highly individualistic viewpoint of 21st century Western Christianity, Pearce’s friends may seem to have been mistaken in refusing to send him to India.

If, during his month of fasting and prayer, he felt he knew God’s will for his life, was not the Baptist Missionary Society executive wrong in deciding as they did? And should not Pearce have persisted in pressing his case for going?

While these questions may seem natural to ask given the contemporary cultural matrix, Pearce knew himself to be part of a team.

He was more interested in the triumph of the team’s strategy in Christ than in the fulfilment of his personal desires.