Recently I picked up a little booklet entitled What about other Religions? by Nicky Gumbel. Advertising itself as an ‘Alpha Resource’, the booklet seeks to tackle issues arising from the interaction of Christians with those of other faiths.

Two questions are raised in the booklet. (1) Is Jesus the only way to God? (2) What about those who have never heard of Christ? Are they eternally lost?

To the first question the booklet answers in the affirmative. Yet regarding the second we are told that many who do not hear of Christ are likely to be saved anyway.

In short this Alpha Resource unashamedly endorses what has come to be known as the ‘wider hope’ theory.

Wider hope?

The ‘wider hope’ theory is grounded on the assertion that people can be saved by virtue of Christ’s death without ever consciously hearing of him or embracing the Good News concerning him.

Citing key figures such as John Stott and J. N. D. Anderson, Gumbel asserts that there are biblical grounds for optimism concerning the fate of the unevangelised.

However, this is not an optimism arising from the church’s faithfulness to the Great Commission (which calls us to take the gospel to every tribe, nation and tongue).

Rather, it is the suggestion that such can be saved without anyone taking the gospel to them at all!

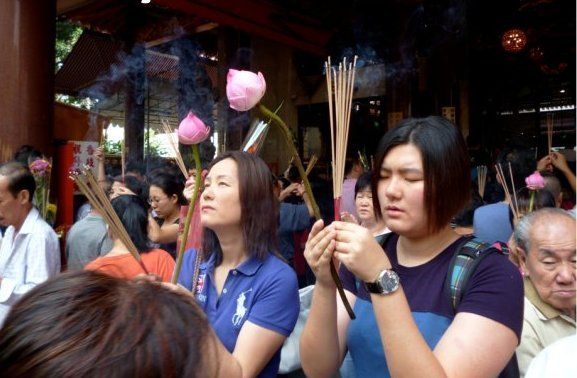

It does not take much imagination to see how this aberrant belief alters the world’s redemptive landscape. Rather than seeing the world as a harvest field of unreached peoples, we are led to believe that the planet is populated by millions of ‘anonymous Christians’.

These people are going about their business as Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus and Animists, totally oblivious to the person and work of Christ, yet are actually saved by Christ.

The question is whether these incredible claims can actually be true. And, indeed, what is the warrant for such breathtaking pronouncements?

Faith Missions

Of course, ours is not the first generation to ponder the fate of those who have never heard the gospel. Earlier generations also faced up to such issues, but responded in a very different way.

The ‘wider hope’ theory of modern missiologists divests the church of any urgency or even rationale for reaching the lost. But earlier missionary statesmen inspired the church to reach out on the basis of the opposite convictions.

In his book The story of Faith Missions, Klaus Fiedler points out that the great missionary movement of the 19th century was impregnated with the conviction that people cannot be saved without responding to the gospel.

He writes: ‘In faith mission publications there are no hints that non-Christians might find a way to salvation within their own religions. Nor are there any hints that for those who never had a chance to hear the gospel there might exist some other way of salvation’.

Significantly he adds: ‘In the manifold primary sources I could not find any other tendencies than those described here’.

Lostness

To anyone who knows anything about the history of faith missions, it is manifestly apparent that dedication to world-wide evangelism was born out of great anguish of heart in response to a theology of ‘lostness’.

Furthermore, this theology was grounded in a reverential submission to the teaching of Holy Scripture.

Thus, when we examine the testimony of godly men such as Hudson Taylor, Adoniram Judson or C. T. Studd, we discover individuals whose lives were shaped by a very different set of convictions to those presently embraced by a whole generation of Evangelicals.

Neither were their concerns established by completing the modules of an MA in missiology! Rather, they were born in the fires of the great revival of 1859 and forged in agony of spirit.

As the full import of God’s Word impacted their lives, it was impossible for such men to remain ‘at ease in Zion’ (as ‘wider hope’ advocates would have us be).

Burden

Hudson Taylor writes: ‘On Sunday June 25th 1865, unable to bear the sight of a congregation of a thousand or more Christian people rejoicing in their own security while millions were perishing for lack of knowledge, I wandered out on the sands alone in great spiritual agony’.

Neither was this crushing burden unique to Hudson Taylor. Time and time again we are confronted with such anguish of heart in the lives of earlier spiritual giants who gave themselves as living sacrifices to take the gospel to the unevangelised.

In the light of this, we should not be impressed with the apparent credentials of those who advocate a ‘post-modern’ view of the Great Commission.

Writing to the Galatians on toxic trends in the world of theology, Paul states: ‘We did not give in to them for a moment, so that the truth of the gospel might remain with you’ (Galatians 2:5).

In the same way, we ought not to give ground to those who question the raison d’être of the Great Commission and its implications for those outside of Christ – not even for a moment.

The doctrine of silence

In his book One Way Dr Hywel Jones points out that most proponents of ‘wider hope’ theories claim that the fate of the unevangelised is not formally addressed in Scripture. The Bible, they say, is quite silent on the matter.

Now this assertion by Stott and others seems rather odd, for two reasons.

First, if indeed it is the case that we cannot reliably discover from Scripture the fate of the unevangelised, then on what basis have Cotterel and others constructed their ‘wider hope’ theology?

Is it a theology built on a doctrine of silence? There is something counter-intuitive about theological assertions for which the absence of biblical authority is the sine qua non of the argument.

It sounds suspiciously like a lawyer who presses the merits of his case on the grounds that no evidence actually exists for it.

Secondly, many people who read the Bible every day find that God’s Word does speak clearly and pervasively to the issue. Indeed, a great many godly people have risked their lives because they regard these things as plainly taught in Scripture.

Appeal to justice

Peppered throughout contemporary theological writings is the assumption that a strong case for wider hope theories can be made by appealing to justice.

It is deemed unjust of God to condemn people for not obeying a gospel message which they have not heard.

But is not this something of a straw man? I for one have never heard anyone arguing that God will hold people responsible for something they did not hear.

Certainly, rejecting the gospel can add to a person’s accountability. But not hearing it cannot increase anyone’s guilt.

The perceived injustice is illusory because the argument fails to discern the real issues.

The real issues

On the day of judgement God will dispense justice to all who are morally accountable to him, that is, all mankind. No distinction will be made, and all will be treated impartially.

Rather than all being judged for what they did not know (as ‘wider hope’ apologists assert) the Bible teaches precisely the opposite! According to Scripture we shall all be judged for what we did know and how we did live, as is clearly taught in Romans 1:18-32 and Revelation 20:12.

As to the underlying complaint that some will be lost who deserved to be saved, it would appear that Shakespeare had a better grasp of the issues than some theologians.

In The merchant of Venice he wrote: ‘Though justice be thy plea, consider this: that in the course of justice none of us should see salvation’.

In God’s sight ‘there is no one righteous, no not one … there is no one who does good, no not one’ (Romans 3:10-12). If justice is our plea, then surely we have no hope, whether we have been evangelised or not.

No; salvation is not the outworking of any moral claim we have on God, but is entirely dependent on God’s grace. There can be no miscarriage of justice in such a scheme of things.