Christian Ministries evangelist John Blanchard has written a major treatment of the subjects of atheism and agnosticism. His intention is to help Christians cope with the rising tide of scepticism in today’s society. The result is a 656-page hardback, Does God Believe in Atheists? which Evangelical Press has already called its ‘Book of the Year’.

The book summarises atheistic and agnostic thinking over the past 2,600 years, and highlights those whose ideas colour today’s secular thinking and humanistic morality. Darwinism and the supposed conflict between science and religion are examined. He also unmasks the fatal flaws in nine world religions and fourteen major cults.

Unusually, there is no mention of the Bible for the first seventeen chapters, which aim to expose atheism on its own terms. From then on, however, the book leans heavily on Scripture, and ends by showing that the ultimate deathblow to atheism lies in the person and work of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Here is an edited extract which examines some of the things that separate humankind from all other species.

Generally speaking, even atheists agree that human beings are creatures of great dignity. As R. C. Sproul says: ‘We want our lives to count. We yearn to believe that in some way we are important … we bicker about a host of things, but at one point we are all in harmony: every person among us wants to be treated with dignity and worth’.

It is not difficult to see that this immediately raises a huge problem for the atheist; where do we get such an idea? One atheistic philosopher says, ‘Man is a grown-up germ, sitting on one cog of one wheel of a vast cosmic machine that is slowly but inexorably running down to nothingness’. How can this be a source of dignity?

The contemporary thinker William Lane Craig says that on this basis, ‘Mankind is no more significant than a swarm of mosquitoes or a barnyard of pigs, for their end is all the same. The blind cosmic process that coughed them up in the first place will swallow them all again’.

Far from dignifying man, atheism degrades him. The atheist begins by saying there was no dignity in man’s origin, which came about as a result of the accidental stirrings of primeval sludge. He sees no dignity in human life itself, echoing Shakespeare’s statement that ‘Life… is a tale, told by an idiot, signifying nothing’. Finally, he holds out no hope of dignity after death. In other words, atheism says that man began as a fluke, lives out a farce and will end as fertiliser. There is not much dignity in that scenario!

Human rights

The issue of human dignity is closely tied to that of human rights, a concept which goes back at least as far as Plato and Aristotle and takes in the Magna Carta, the American Declaration of Independence, and a present-day plethora of organisations devoted to the cause of human rights. Prince Charles was hardly exaggerating when he said, ‘We live in a world of rights’.

In his ‘Sacred and Profane’ column in the Daily Telegraph, Clifford Longley agreed: ‘The most significant moral transition of the past 50 years, which shows no sign of slowing down, is the change from the idea of sin to the idea of rights … Time and again, when philosophers, lawyers, politicians and teachers turn their attention to what might be the bedrock of modern morality, they select “human rights” as the best option’.

It is not difficult to see why the atheist has problems with the issue of human rights. Can he explain why similar rights should not be extended to all other creatures? With his radical idea of ‘speciesism’, the Australian bioethicist Peter Singer claims that some animals (whales, dolphins and apes, and possibly monkeys, dogs, cats, pigs, seals and bears) are ‘non-human persons’ and that it is just as wrong to hurt or kill them as it is to hurt or kill a human being.

Yet he then gets in a tangle by removing the automatic rights of protection from unborn babies and those up to one month old, and bluntly claims, ‘Killing a defective infant is not morally equivalent to killing a person. Very often, it is not wrong at all’.

Interviewed by Boris Johnson in the Daily Telegraph, he said that if he could save a child or the last Bengal tiger he would save the child – but that if the child was a disabled orphan and the tiger was starving and could not catch the child without assistance, he would shoot the orphan.

Guilty foxes?

This will seem abhorrent to most people, but can the consistent atheist find a reason to disagree? Are animals really on a par with humans? Can animals have similar rights to humans if those rights are not balanced by moral and social responsibilities?

Are animals answerable for their actions? Are foxes ‘guilty’ if they bite the heads off chickens or (and I write with feeling here) steal golf balls? Should cats who play with wounded mice be brought to account? If we should give ‘rights’ to whales, dolphins and gorillas, why not to hyenas, jellyfish and dung beetles? The logic seems unanswerable.

The fact of the matter is that a creature that shares 98.4% of DNA with humans (as some do) is not 98.4% human, any more than a fish that shares, say, 40% is 40% human.

Secondly, on what atheistic basis do human beings have any rights? Where can the atheist discover rights to justice, freedom, happiness, health, security, or even life itself? If human beings are nothing more than complex biological machines, which came into existence by accident, why should they have any more rights than any other objects in the universe?

If human rights are merely benefits granted by international or other organisations, or loosely agreed at some social level or another, how can we object when (as is often the case) they are later denied as emphatically as they were granted?

Endowed by the Creator

Thirdly, without a transcendent basis for human rights, why should anyone be concerned about the needs of other people? Richard Dawkins claims that our existence and survival are only ‘means to an end’, the end concerned being reproduction. But if this is the case, why should disablement, mental derangement, unemployment, hunger, poverty or drug dependency be causes for concern? To quote R. C. Sproul again, ‘Why should we care at all about the plight of insignificant grown-up germs?’

Even a deist like Thomas Jefferson, who drafted the American Declaration of Independence, claimed that the ‘inalienable rights’ of human beings, including those to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’, were not acquired or invented at some point in human history, but were ‘endowed by their Creator’.

The American and French Revolutions were pivotal in raising the profile of human rights, and it is striking that the deistic leaders of both took a supreme Being as their starting-point and insisted that man’s rights are inherent in his creation.

What it means to be human

On this issue at least, theists confirm what these deists claim. Human rights can be properly discussed only when we have established what it means to be human. When his Cape coast home was ransacked in 1998 for the second time in a year, and four members of his neighbour’s family brutally murdered by an intruder, the South Africa golfer Ernie Els made an impassioned plea to the government to curb ‘the sickening wave of crime which is engulfing and destroying our country’.

Speaking to Johannesburg’s Sunday Times, he protested, ‘Our rights as human beings are being taken away from us’. Els was not making a religious statement, but in speaking about ‘our rights as human beings’ he was unconsciously putting his finger on the neglected truth that it is as human beings created by God that we have whatever ‘rights’ we can properly claim.

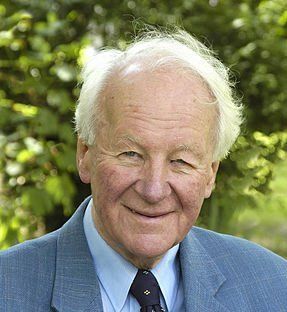

John Stott is right on the ball here: ‘The origin of human rights is creation. Man has never “acquired” them. Nor has any government or other authority conferred them. Man has had them from the beginning. He received them with his life from the hand of his Maker. They are inherent in his creation. They have been bestowed on him by his Creator’.

Unique relationship

This is not to say that animals have no rights, for they too are part of God’s creation. But these rights fall short of those granted to beings who stand in a unique relationship to God. Theism sees ‘human rights’ not as personal preferences which we can demand to be met, but as privileges granted by God and which he requires us to respect in others.

This picture provides the perfect framework for equal rights, as it says that man’s highest worth (and therefore his most valid claim to ‘rights’ of any kind) lies in a creative act which bestows equal status on all human beings without any discrimination of any kind. It also points powerfully towards our responsibility to secure and defend other people’s rights, even if we have to forego our own in order to do so.