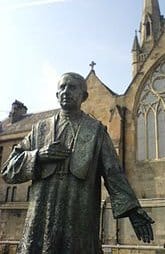

The death of Cardinal Basil Hume in June marked another milestone in the seemingly inexorable advance of Roman Catholicism in Britain. Instead of entertaining the historic English antipathy towards Roman Catholicism, many people now view Catholic ‘insights’ as legitimate variations on the truth. This is a far cry from what obtained at the time of the Reformation, or even two hundred years ago. during the last thirty years, Roman Catholicism has moved ever closer to centre-stage. And perhaps one of the most important factors in this has been the influence of the late Cardinal Basil Hume.

Thousands attended Hume’s lying-in-state and funeral at Westminster Cathedral. Protestants, Jews and Muslims joined with Catholics in acclaiming his ‘holiness’. When, previously, the advanced state of Basil Hume’s cancer became known, the Queen lost no time in bestowing upon him an unprecedented honour, the ‘Order of Merit’. Widely reported, too, was her other supposed accolade, implicit in the epithet, ‘my’ Cardinal.

What is the story behind this influential man? Basil was born in Newcastle in 1923. He was brought up a Catholic by his French mother (his father was an eminent, but agnostic, English physician), and later sent to Ampleforth College, a Roman Catholic public school.

In 1941, at the age of eighteen, he entered Ampleforth Monastery as a Benedictine novice. Between 1944 and 1951 he studied history at St Benet’s Hall in Oxford, and theology at Fribourg University in Switzerland. He was ordained priest at Ampleforth in 1950, and from 1952 became Senior Master in modern languages at the college. In 1963 his fellow monks elected him abbot. From Ampleforth, Hume was the surprise (but shrewd) choice of the papal nuncio to be Archbishop of Westminster. That was in 1976. He was also then made Cardinal of England and Wales.

Benedictine spirituality

For the next twenty-three years his style reflected his days as a Benedictine abbot. He liked to be called ‘Father Basil’. He presided with undemonstrative but firm authority over a diverse Catholic community still grappling with the implications of Vatican II. But Hume, a skilful leader, kept the Roman Catholics together.

He united ultramontane Catholics, English Catholics and other disparate factions. He successfully held together progressive liberals and conservative advocates of the Tridentine Mass. He managed to accommodate the new liberalism, while remaining true to Catholic teaching. He was looked upon as ‘a safe pair of hands’ by Rome.

The social standing of Roman Catholics in England was also climbing although, surprisingly, this trend was not matched by an increase in the numbers attending mass. Still, it is a measure of the quiet success that Hume enjoyed, that he was mooted by some as successor to Pope John Paul II.

Modestly self-deprecating and prayerful, Hume seemed to epitomise the monastic ideal of ‘Benedictine spirituality’. At the same time, he contrived not to appear un-English to his contemporaries. Perhaps this was in part because he avoided overexposure to the media. He did not go public on every issue. When he did assert his influence, it was privately and infrequently, and correspondingly to great effect. For example, it was probably Hume’s canvassing that lay behind the release of the ‘Birmingham Six’ and the ‘Guildford Four’.

It was not long before society’s opinion-formers began to knock on Cardinal Hume’s door, and it was eventually to him the media turned during times of national crisis and moral debate. Hume seemed to possess the authority that was lacking at Canterbury.

Practical ecumenism

Other momentous events took place during his arch-episcopacy. Persuaded by the Cardinal, Pope John Paul II visited Great Britain in 1982, the first time a pontiff had done so since the Reformation. Then, in 1990, Hume led Roman Catholics in Great Britain into ecumenism ‘at grass-roots level’. Now, for the first time, ordinary Catholics were involved with Protestants in practical ecumenism. The Inter-Church Process proved a powerful solvent to lingering Protestantism within Protestant denominations!

The next major event to occur was the landmark decision of the Church of England, in November 1992, to ordain women to the Anglican priesthood. The Anglo-Catholics could stomach no more. A large-scale defection from that church to Rome ensued. Hundreds of lay people were received into the Catholic fold, as well as dozens of Anglican priests. These converts included Dr Graham Leonard, the former Bishop of London, and prominent politicians like Ann Widdecombe and John Gummer.

Hume himself admitted during the heady days of 1992 that Anglican disaffection with women’s ordination could be ‘a big moment of grace, it could be the conversion of England for which we have long prayed’. This was an uncharacteristically unguarded statement, which he tried to explain away. But the proof of the pudding has been in the eating!

Empathy

Hume worked hard to maintain close links with Lambeth Palace and the Anglican bishops. He knew that Catholic resurgence, for all its apparent buoyancy, was still in a fragile phase. There must be no triumphalism; nothing should be done to raise old spectres. Only some sixty years previously, in 1935, Arthur Hinsley, later to become Cardinal, had faced a stony response when he had tried to present to King George V a loyal address on behalf of English Roman Catholics.

Undoubtedly the prize for Hume was the conversion of the Duchess of Kent, in which he played no small part. His relaxed style, as he talked with enquirers over a cup of tea and empathised with their inner struggles, was employed to great advantage.

Hume knew that for centuries Catholic priests had been perceived by the English as representatives of a foreign religion, ministering to Irish immigrants, perhaps, but still with a proselytising agenda. The conversion to Rome of several prominent literary figures, like Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene during the 1920s, would have done nothing to dispel that view. But now these perceptions were changing.

Biblical criteria

None can fairly doubt the ability of the late Cardinal. But was this ability matched by true spirituality according to biblical criteria? Sadly the answer must be ‘no’. Basil Hume made his beliefs clear to all. For example, he had published on the Internet a series of meditations entitled Spiritual Reflections, as well as several of his lectures and homilies. These show that, for all his apparent piety, he was ignorant of the true gospel and unqualified to be anyone’s spiritual guide. While he bore witness to the aridity of postmodernism (see Jesus Christ Today and Searching for purpose: God and the future of our society), he did not point enquirers unambiguously to Christ alone.

Take these words from a homily about the ‘Holy Year 2000’. ‘Christ is our Way, our Truth, our Life. It is to Him that we must turn’. That sounds promising. But it is soon followed by, ‘Mary, His Mother and ours, must be with us constantly as we prepare for the Holy Year’. Or examine these sentiments, expressed in a meditation on faith: ‘Prayer to Our Lady can deepen our faith in Jesus Christ her Son and His presence in the Eucharist’. Such statements tell their own sad story.

Once for all

The fact is, that ‘there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus’ (1 Timothy 2:5), and Mary rejoiced in that mediator; ‘my spirit has rejoiced in God my Saviour’ (Luke 1:47). Hume’s trust, it seems, was not in Christ alone. He subscribed to the ancient heresy of Mariolatry although, admittedly, often in muted tones. The evidence suggests that he knew nothing of the joy that Mary had in a Saviour from sin, but was working to achieve his own righteousness. However, ‘by the deeds of the law there shall no man be justified in [God’s] sight’ (Romans 3:20).

This is not to deny kindly features in Hume’s character. But to exhibit such qualities is not the same as possessing saving faith. The latter only comes through redemptive grace, leading men to trust in the merits and death of Christ. The Lord Jesus Christ died and was raised from the dead two thousand years ago as an objective, completed sacrifice for the sins of his elect people. ‘We are sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all’ (Hebrews 10:10). Christ made, at Calvary, a ‘full, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world’ (Book of Common Prayer). For all the massed choirs and decorum of the Cardinal’s funeral, there is little evidence that Hume was depending on the finished work of Christ for salvation. This is the scale of the spiritual tragedy.

No more sacrifice

In contrast to this teaching, the Cardinal’s Spiritual Reflections maintain that in the mass there is a ‘re-enacting’ of the sacrifice of Christ, through the ‘consecrated bread and wine’. ‘Is not the Mass both Sacrifice and Communion?’ he asks. ‘For every time the Mass is said the Sacrifice of Calvary is repeated’. And again, ‘The Real Presence is actually in the consecrated bread and wine’, and ‘the presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament – Christ wholly present, body, soul and divinity’.

The Thirty-Nine Articles answer such assertions thus: ‘Transubstantiation … is repugnant to the plain word of Scripture, overthroweth the nature of a Sacrament, and hath given occasion to many superstitions … The sacrifices of Masses … [are] dangerous deceits and blasphemous fables’.

About one hundred years ago J. C. Ryle, Bishop of Liverpool, said that the young King Edward VI prayed on his deathbed in 1553, ‘O my Lord God, defend this realm from Papistry, and maintain thy true Religion’. Ryle then cited the litany: ‘From all sedition, and privy conspiracy, from the tyranny of the Bishop of Rome and all his detestable enormities, from all false doctrine and heresy, from hardness of heart, and contempt of the Word and commandments, good Lord, deliver us!’ Such prayers are still necessary.