In October 1889 a young man by the name of D. C. Davidson left his home in Michigan to go abroad to do post-graduate work in theology. His mother had wanted him to study at Yale, but he was determined to come into vital contact with what he called ‘the leading minds of Europe’.

After a stay of four months in Edinburgh, he crossed over from Great Britain to Germany in 1890 and eventually made his way to Berlin. Yet, instead of being a place where his faith was deepened and established, the German capital proved to be a veritable furnace in which his faith in God was tried to the very depths.

Of his time in Berlin he said that a ‘horror of great darkness’ came over his soul, as he was exposed to liberal German theology. ‘I have encountered many a fiery temptation’, he later wrote, ‘but I have never had a temptation cross my pathway so subtle and dangerous as that of German destructive criticism’.

Pentecostal fire

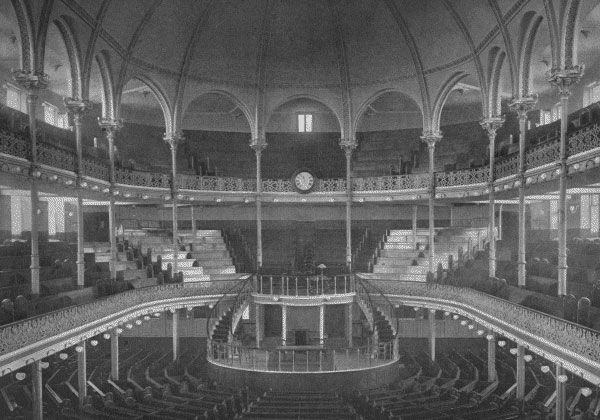

With his faith well-nigh shattered, he returned to England, where for three months he regularly went to hear Charles Haddon Spurgeon preach what must have been some of his final sermons. The American student’s description of the services he attended at the Metropolitan Tabernacle provides an excellent introduction to this appreciation of Spurgeon’s defence of historic Christian orthodoxy.

‘When Spurgeon preached the simple old doctrines of the Cross, the pentecostal fire fell from heaven upon the people. I have seen the multitudes in that tabernacle moved by the breath of God, when that man spoke, as the trees of the forest are moved by the wind. It seemed to me that I was in the third heaven, compared to the cesspool of German criticism in which I had been wallowing. What could I do but bow down before my Maker and worship, crying, “The Lord, He is God! The Lord, He is God!”…The glory of God seemed to fill Mr Spurgeon’s tabernacle … The poisonous effects of the destructive criticism, which had permeated my heart, were consumed like stubble by the holy fire of God. I saw the Scriptures with new eyes. They became inexpressibly precious to me [as did] the Christ whom they reveal’.

While Spurgeon was involved in a wide variety of ministries, he is best known as a preacher, as this account well illustrates. Indeed, Davidson’s description of his preaching highlights what were the four leading characteristics of Spurgeon’s sermons. They were: Christ-exalting and centred on the propitiatory death of Christ; designed to draw sinful men and women to worship the one true God; rooted in and circumscribed by the Scriptures; and resplendent with what Davidson calls the ‘pentecostal fire…from heaven’.

Early years

Charles Haddon Spurgeon was born into a godly home in the heart of rural Essex on 19 June 1834. Spurgeon’s forebears originally came from the Netherlands, which they had left in the 1500s due to religious persecution. Both his father, John Spurgeon, and his grandfather, James Spurgeon, were Congregationalist preachers, and it was during an extended stay over a number of years in the home of his grandfather that Charles discovered a library of Puritan folios.

Despite Spurgeon’s tender years, and the fact that as a young child he found it very difficult to lift these large and weighty volumes, he would later write that as a boy he was never happier than when in the company of these Puritan authors. In time, Spurgeon would be rightly convinced that commitment to the Calvinism and spirituality of the Puritans was vital for the orthodoxy and well-being of Baptist churches.

However, despite such godly surroundings, it was not until 13 January 1850 that Spurgeon was soundly converted. The story of his conversion at what was then a small Primitive Methodist chapel called Artillery Street Chapel (now Spurgeon Memorial Evangelical Church) is well known, and does not need to be retold here. For Spurgeon’s own inimitable, and at times humorous, account of his conversion, the reader is referred to C.H. Spurgeon: The Early Years, 1834-1859 (Banner of Truth Trust, 1962), pp.87-88.

Four months later, on 3 May, with the agreement of his Congregationalist parents, Spurgeon was baptised in the River Lark, not far from Isleham in Cambridgeshire. After his baptism Spurgeon found an unquenchable desire to serve Christ. He began to speak more publicly, and his compelling preaching soon led to an invitation to pastor the Baptist church in Waterbeach, a small hamlet a few miles north-east of Cambridge. Spurgeon laboured here from the autumn of 1851 to April 1854. In those two and a half years, the membership of the small Baptist chapel more than doubled, going from forty to 100.

Park Street Chapel

Hearing of his scintillating preaching, the deacons of Park Street Chapel, a historic London Baptist congregation, invited him to preach on 11 December 1853. The people who heard Spurgeon that Sunday were thrilled with his preaching, and the deacons quickly arranged for Spurgeon to return on three Sundays in January 1854. He was subsequently invited to supply the pulpit for several months, and in April of that year, at the age of nineteen, he accepted a call to be the pastor of the church.

The church was built to seat 1,200, but it soon proved far too small for the crowds that sought to sit under Spurgeon’s preaching. In 1855, therefore, the chapel was expanded to seat 1,500. A year later, however, this enlarged chapel had also been outgrown, and the decision was made to build what would become known as the Metropolitan Tabernacle. Completed in 1861, the Tabernacle could seat 5,000 and accommodate another 1,000 standing. For the rest of Spurgeon’s pastorate, the Tabernacle saw an average of 5,000 at each Sunday morning and evening service. And while Spurgeon and his fellow elders were careful not to make a high membership their goal — indeed Spurgeon had a healthy distrust of all such statistics — 14,691 were added to the church during Spurgeon’s time there, of whom roughly 10,800 were by conversion and baptism.

The Prince of Preachers

Spurgeon’s success as a preacher certainly owed little to his physical appearance, for he was of average height, fairly stout as he grew older, and had two unduly prominent front teeth. In the words of a certain Monckton Milnes, ‘When he went into the pulpit, he might be taken for a hairdresser’s assistant; when he left it he was an inspired apostle’. Augustine Birrell records that when he went to hear Spurgeon preach, the only seat he could find was in the topmost gallery, between a woman eating an orange and a man sucking peppermints. Finding this combination of odours unendurable, he was about to leave, when, he said, ‘I heard a voice and forgot all else’. In the words of recent biographer, Mike Nicholls, Spurgeon possessed ‘one of the great speaking voices of his age, musical and combining compass, flexibility and power’.

Spurgeon, though, looked to quite a different source for the blessings which attended his ministry. In a speech at the celebration of his fiftieth birthday in 1884, he forthrightly declared that the blessing he had enjoyed in his pastorate ‘must be entirely attributed to the grace of God, and to the working of God’s Holy Spirit… Let that stand as a matter, not only taken for granted, but as a fact distinctly recognised’.

The Down-Grade controversy

When Davidson’s faith was rekindled through the sermons of Spurgeon in the early 1890s, the Baptist preacher was a dying man. For a number of years he had suffered from a disease of the kidneys. This physical problem appears to have been exacerbated by his involvement as one of the leading protagonists in what is known as the Down-Grade controversy. During the 1880s Spurgeon was concerned by what he rightly saw as the inroads of liberal theology into British Baptist ranks. Sensing that something definite needed to be said to the issue, he published a series of articles in The Sword and the Trowel over the course of 1887, in which he urged his fellow Baptists to deal with the problem head-on and proclaim their wholehearted commitment to evangelical orthodoxy.

As Spurgeon examined the preaching of some of his Baptist contemporaries, he had noticed in their sermons that the ‘Atonement is scouted, the inspiration of Scripture is derided, the Holy Spirit is degraded into an influence, the punishment of sin is turned into fiction, and the resurrection into a myth’. Spurgeon’s protest, however, fell largely on deaf ears, and in October of that year the Baptist preacher felt he had no recourse but to lead the Tabernacle out of the Baptist Union.

Commitment to truth

Over the winter of 1887-1888 a naïve, though well-intentioned, group of peace-making individuals within the Union made common cause with some of Spurgeon’s opponents to attempt a reconciliation between the pastor of the Tabernacle and the Union. Spurgeon, though, rightly chose commitment to the truths of the Scriptures over the preservation of denominational unity, and these attempts at reconciliation failed. The climax came at the annual meeting of the Baptist Union in April 1888. Spurgeon was not present, though his brother, James Archer Spurgeon, the co-pastor of the Tabernacle, was. Spurgeon’s supporters, and the eirenicists (peace-makers) within the Union, had both drawn up doctrinal statements. Prior to the debate about the issue on 23 April however, a mediating statement was drafted and overwhelmingly accepted by the delegates at the meeting. Those of Spurgeon’s supporters who voted in favour of this statement — including Spurgeon’s own brother, James, who seconded the approval of the statement — actually believed that they had won a great victory. Spurgeon was convinced otherwise and the succeeding decades showed that he was right.

As historian Willis B. Glover has written: ‘Spurgeon’s insight into the religious life of his own times was proved by subsequent events. He did stand on the eve of a great evangelical depression, and unquestionably the theological confusion of his day and the disturbance to religious traditions wrought by higher criticism had a great deal to do with the decline of evangelicalism’.

Spurgeon recognised that without clear and distinct doctrinal parameters, evangelicalism was helpless against the onslaught of liberal theology. Many of the eirenicists within the Union felt that it would not intrinsically affect or harm Christian spirituality to accept the new theological perspectives, spawned by the rise of higher criticism. Spurgeon saw the folly of such a position: ‘the coals of orthodoxy are necessary to the fire of piety’.

Death and legacy

The stress of this controversy took a great toll on Spurgeon, and almost certainly contributed to the rapid decline in his health during 1891. He died at Menton, a resort on the French Riviera not far from the Italian border, where he had taken annual vacations since the mid-1870s. Spurgeon had gone there with his wife in October 1891, hoping that a change of scenery and weather would facilitate a recovery of health. It was not to be. The Prince of Preachers died in the last hour on the final day of January 1892.

Spurgeon’s lasting memorial was in the lives of countless men and women who had been converted and built up in the faith by the Spirit of God working in his life and ministry. D.C. Davidson was a good example of this. When Davidson returned to the United States, after sitting under Spurgeon’s preaching, he did so with the resolve ‘that while life lasts, I would “preach the Word” and blow the gospel trumpet with no uncertain sound’.

Although Spurgeon’s voice was stilled in 1892, the Holy Spirit continues to honour Spurgeon’s ministry through the ongoing publication of his sermons, drawing sinners to know and worship the Triune God. On the other hand, the preaching of his theological opponents, such as William Landels and John Clifford, today remains unknown to any but scholars. Little wonder that the twentieth-century Lutheran preacher and theologian, Helmut Thielicke, once suggested with regard to Spurgeon’s sermons: ‘Sell all you have…and go buy Spurgeon’.

Note: For D. C. Davidson’s account of his experience, see ‘In the Furnace of Unbelieving Theology’, The Banner of Truth, 293 (February 1988), 16-18.