One hundred years ago on Friday 3 May 1895, to Ite and Klazina Van Til a sixth child, Cornelis (sic), was born. The birth took place on a forty-acre farm in Grootegast, Holland, in a solid old farmhouse with its red tile roof and attached barn.

The end of the nineteenth century was a time of passionate religious controversy in the Reformed churches of the Netherlands. The issue was the true nature of experiential Christianity. The debate’s focus became infant baptism.

The majority believed that at baptism a child became regenerated and that that presumption ought to characterize how it was addressed and nurtured. A minority, known as the Afscheiding, opposed this position: they also practiced infant baptism but were convinced that baptized children needed to exercise true repentance and make personal appropriation of the Saviour. For them it was crucial that baptized children were not presumed to be regenerate but rather urged to turn in faith to God.

Van Til’s grandfather Reinda, who was an inn-keeper, had identified himself with this party. They were barred from meeting in church buildings and so came together in barns or hired rooms until new meeting houses were erected. Van Til’s father was also one of the Afscheiding. He was a strong man with a flowing beard, who was much revered by his seven sons (the one daughter died as a baby). Cornelis acquired the nickname Kees (pronounced ‘Case’) by which designation friends on the faculty at Westminster Seminary referred to him.

The Van Til boys attended the nearest Christian school two miles away from the farm. They all wore their klompa, except during school hours when they were forbidden to keep their clogs on as they could become vicious weapons in playground fights. In their home the boys were raised on the Heidelberg Catechism and attendance at the local church. One saying of his father’s always stuck in Cornelis’s mind: ‘You can’t drop salt on every snail.’ In other words, don’t run after every issue that you meet: life is too short.

Emigration

Cornelis’s brother Reinder was eleven years his senior, and when he married he emigrated to live in Highland, Indiana, USA. Forty acres cost five dollars an acre, and enthusiastic letters home urged the family to join Reinder in the land of opportunity. So in the spring of 1905 the Van Tils, except for brother Hendrik who had joined the army, sailed from Rotterdam to New York, arriving two weeks after the tenth birthday of that son who was to be known in America by the more familiar ‘Cornelius’.

They took the Erie Railroad on a twenty-six hour journey to Illinois. In Highland, they were met by Reinder and introduced to the six landmarks of the community: the post office, school, blacksmith shop, railway station, tavern and Christian Reformed Church.

Cornelius did well in school, mastering English in a year. His teacher nicknamed him Big Klompa. After school he helped his father in growing and harvesting cucumbers: it was wearying work. He sold the farm’s vegetables from door to door in neighbouring towns, and took Nellie the farm horse to the blacksmith to be shod. Van Til had farming in his blood and was never happier than working with a hoe, planting and weeding.

The call to the ministry

At nineteen years of age he had an overwhelming constraint to become a preacher. The words of Isaiah 6:8: ‘Lord, here am I, send me,’ were engraver on his heart. In Grand Rapids he attended Preparatory School for Calvin Seminary. He was initially homesick for his wonderful family and for a certain Rena Klooster, though marriage was to be ten years away.

His education was totally Dutch in its ethos: his lifelong admiration for the work of Abraham Kuyper developed at this time. Those slightly old-fashioned, somewhat florid touches one discovers in Van Til’s sermons, as well as the classical nuances in his writings, are due to Kuyper’s influence. But Van Til was much more than a clone of Kuyper. He followed Geerhardus Vos’s biblical theological insights and so transcended the levelling approach to Scripture which characterizes Kuyper.

In 1921 he had enrolled in Calvin Theological Seminary and was taught by such men as Louis Berkhof. While he was there the life-changing decision was taken to continue his studies at Princeton Seminary under Vos, Casper Wister Hodge, Robert Dick Wilson, O.T. Allis and J.Gresham Machen.

1921 was the year B.B.Warfield died, so Van Til did not meet him, though Warfield’s influence was pervasive. Van Til lived on the fourth floor of Alexander Hall (along the corridor from Machen’s bachelor apartment), a literal stone’s throw from Warfield’s old home.

In fact Van Til was never taught by Gresham Machen (who was fourteen years older than him) because he had already taken those New Testament courses which Machen was giving during his years at Calvin Seminary.

Cornelius helped to pay his way through Princeton by working as a seminary waiter, and later managing the student dining club. He also took courses in philosophy at Princeton’s University. This exposure to American Presbyterianism and the liberal ethos of university life broadened Van Til’s experience of the twentieth century’s battles for historic Christianity.

The battle for Princeton

It was Geerhardus Vos who persuaded Van Til to get involved in the fight for Princeton Seminary and for the heart of the United Presbyterian Church. ‘Why’, protested Van Til, ‘should I, an outsider, get mixed up in a denominational skirmish when I’m not in the denomination?’ Vos replied soberly, ‘This is going to be a much broader matter than a single denominational issue. Princeton may be a Presbyterian Seminary, but don’t forget that it’s a rallying point for many wonderful Christian people all over the world – people who love Reformed doctrine and life. You cannot, you dare not, stand by and look on like a spectator when the conflict is being fought.’ When Geerhardus Vos died in the summer of 1949 Van Til officiated and preached on 2 Corinthians 5:1.

In 1925 Cornelius and Rena were married and began their life together in Princeton. After two years he was received into the Classis of Muskegon, Michigan, and accepted a call to the only church he was to pastor in Spring Lake, Michigan, caring for seventy Dutch families.

What he expected to be his lifetime’s work lasted only a year as an invitation came from Princeton to become a lecturer in apologetics. He was the youngest member of the faculty, and he and Rena loved the quiet streets of Princeton and the friendship of Vos and Gresham Machen

Then the great crisis hit Princeton: at the General Assembly of 1929, after a mere thirty minutes’ debate. the delegates voted by 530 votes to 300 to transform the conservative basis of Princeton and establish a new board of trustees.

Immediately Robert Dick Wilson, O.T.Allis, Gresham Machen and Van Til resigned in protest. Van Til returned to his Spring Lake pastorate, while the others determined to establish a new institution to maintain the Princeton tradition. It was called Westminster Theological Seminary and its first classes were held on 25 September 1929 with fifty students.

New faculty were appointed, R. B. Kuiper and Ned Stonehouse, and soon they were joined by Van Til (now the father of a ten-week-old child Earl) summoned for the second time from Spring Lake C.R. Church. John Murray was added to the staff a year later.

Today there are more students studying at the two Westminster campuses in Philadelphia and California than there are in Princeton – let alone all those students in the other four American conservative Presbyterian seminaries modelled upon Old Princeton.

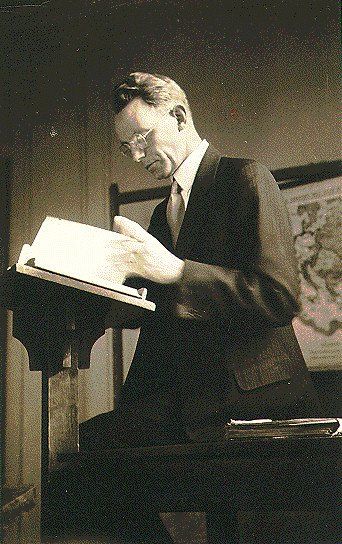

The teacher at Westminster Seminary

For the remainder of his days Van Til’s life was inseparable from his teaching at Westminster Seminary. His lecture notes were expanded and distributed to his students in a series of syllabuses with those enigmatic words on the front page ‘Not to be considered a published work.’

What was it like to be taught by Cornelius Van Til? He did not seem to prepare his lectures. There was constant engagement with the class. It was useless to take any notes: one was expected to have become acquainted with his syllabus. The lectures were rambling dialogues, funny, suddenly illuminating and also confusing, which form was dictated by the complex mix of students before Van Till

All-round Christian

His own piety was real: his prayers at the beginning of the lectures were helpful. His hospital visits and the tract distribution at bedsides, his orthodoxy, even open-air preaching in the middle of New York – on Wall Street on one memorable occasion – built up the image of an all-round Christian. His influence pervaded everything that was taught at the seminary.

The problem remains the complexity of his writing. Men who are five-point Calvinists, who want to be consistently biblical and desire to learn from Van Til, wrestle with his books and put them down in frustration. If all his works had been written as simply as that lovely pamphlet, Why I believe in God, his contribution to evangelical theology would have been considerable. What he has left the church is a legacy of abstruse apologetic writings, vigorous questioning of any deviation from orthodoxy especially by Karl Barth, some glittering insights and a pure faith in the Saviour. What he still needs is a popular interpreter. There have been a number of these, but all as difficult to understand as Van Til.

‘We shall soon meet at Jesus’ feet’ became Van Til’s customary parting words as a grand patriarch. He was greatly loved.