John Calvin (1509-1564) -or, to give him his French name, Jean Calvin – was the most self-effacing of the Reformers. Yet it was this constitutionally shy man who the Lord saw fit to use to rebut the ‘delusive pretensions’ of the Roman Church and establish the Reformed faith on a firm foundation in western Europe. In fact, Calvin is one of the most significant figures in the history of the West. Such diverse areas as the modern market economy, American civil religion, and the French language, not to mention contemporary Evangelicalism, have all been decisively shaped by the life and ideas of this Frenchman. He has been rightly described as ‘the theologian of the Reformation’.

Calvin and Scripture

When John Calvin considered the cause of the Reformation he found himself compelled to look to the Scriptures. For it was when people studied the Scriptures that they were brought face to face with the significant differences between the Church of Rome’s ‘delusive pretensions’ and ‘the order presented by the Lord’ in his Holy Word. They saw that Rome had allowed or encouraged unbiblical traditions to usurp the authoritative place that Scripture alone should occupy.

Yet, in Calvin’s view, even the Scriptures by themselves were not the ultimate cause of that watershed known as the Reformation. There had to be more than an intellectual understanding of what the Bible said. There had to be submission to and acceptance of the divine revelation set forth in the Bible, and this took place only through the illumination of a person’s heart and mind by the sovereign action of God’s Holy Spirit. The Bible was the means whereby God revealed his will to human beings, but the Spirit alone made this revelation efficacious.

Pernicious error

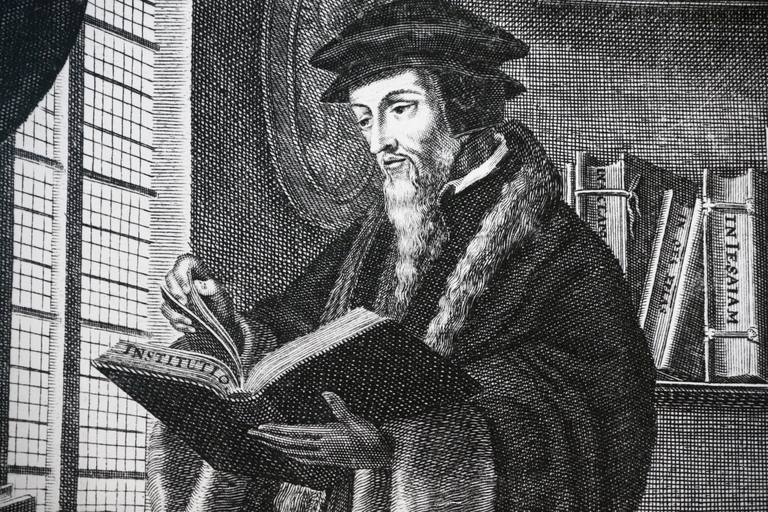

One of Calvin’s clearest rebuttals of Rome’s error in placing her traditions alongside Scripture is found in his major work, the Institutes, Book 1, Chapter 7. Calvin begins by elucidating the position that the Church of Rome held with regard to Scripture and tradition. According to most medieval Roman Catholic writers and theologians, Scripture was authoritative because the church ruled it to be so. According to the Roman position, a believer can find certainty for his faith in the voice of the church. Calvin bluntly describes this view as ‘a most pernicious error’, for it subordinates the divine authority of God’s Word to a human judgement about it (Institutes 1.7.1).

Against this perspective, Calvin first argues that the church itself is founded on Scripture and as proof cites Ephesians 2:20, which unequivocally states that the church is being built upon ‘the foundation of the apostles and prophets’. Calvin appears to understand the phrase ‘apostles and prophets’ to imply their written witness in the Word. Calvin’s argument here is also from temporal priority. The redemption of men and women and their incorporation into the church occurs through the Word; therefore that Word must precede the establishment of the church. Accordingly, it is wrong for the church to pretend to be lord of Scripture when Scripture is the foundation of the church. Contrary to Rome’s claims the church is not a separate, independent source of authority (Institutes 1.7.1).

Secure basis

Calvin argues that Scripture exhibits clear evidence of its own truth and needs no external witness to establish its authority. The church simply recognizes the nature of Scripture and the authority that God has embedded in it, and on this basis declares it to be God’s Word. No church decision makes it God’s Word. Just as something that is sweet is sweet in itself, and does not depend upon human judgement to declare that it is sweet, so Scripture bears witness to its own authority and does not depend upon human judgement for that authority (Institutes 1.7.2).

What then does Calvin feel is the only secure basis upon which the authority of Scripture can be founded? In a word, the only secure basis is the inner testimony of the Holy Spirit. As Calvin notes, ‘These words [of Scripture] will not be given complete acknowledgement in the hearts of men, until they are sealed by the inner witness of the Spirit’ (Institutes 1.7.4). Why is this? Well, first of all, Calvin refers his readers to the basic fact of the Fall. One of the chief results of innate human fallenness is that human minds have become so perverse and corrupted that they fail to see the Scriptures as ‘the living words of God’ (Institutes 1.7.1). As Calvin astutely notes: ‘Although we may defend God’s holy Word against all opponents, it does not follow that we can establish in their hearts the conviction which faith demands’ (Institutes 1.7.4). As he wrote elsewhere, in his comments on 2 Timothy 3:16: ‘Although the majesty of God is displayed in [the Scriptures], only those who have been enlightened by the Holy Spirit have eyes to see what should have been obvious to all, but is in fact visible only to the elect.’

For Calvin, the Bible is ‘the pure Word of God’, a unique text ‘free from every stain or defect’, and for believers ‘the certain and unerring rule’ of life and doctrine. But this view of the Scriptures only comes about when God himself convinces us of this fact. ‘As God alone is a fit witness of himself in his Word, so also the Word will not find acceptance in men’s hearts before it is sealed by the inner testimony of the Spirit’ (Institutes 1.7.4).

The testimony of the Spirit

But what does Calvin mean by the phrase the ‘inner testimony of the Spirit’? What exactly does he have in mind? Well first of all, it is not a new, private revelation, or something that is given apart from God’s Word. What then is it? In the words of J. I. Packer, in a marvellous essay written a good number of years ago on ‘Calvin the Theologian’, it is ‘a work of enlightenment, whereby, through the medium of verbal testimony, the blind eyes of the spirit are opened, and divine realities come to be recognised and embraced for what they are.’ As Packer goes on to state, it is a convincing presentation and demonstration by the Holy Spirit, to the renewed mind and heart, of the claims that Scripture makes concerning its character, enabling the regenerate person to make a faithful response to those claims.

The basis for reform

The practical significance of this doctrine is that it is only when Scripture’s divine origin is acknowledged, that it affects our worship of God and our lifestyle. Calvin and his fellow Reformers were rightly desirous of effecting a great change and reform in the thinking, worship habits and lifestyles of their fellow Europeans. Where was the standard or paradigm of reform to be found, though? Sixteenth-century Europe had its fair share of men and women who wanted to completely revamp life and thought – Renaissance humanists like Erasmus, violent revolutionaries like Thomas Münzer, starry-eyed visionaries like the Zwickau prophets, anti-Trinitarians like Michael Servetus and Fausto Paolo Sozzini, and communitarian Anabaptists such as Menno Simons. What, then, were to be the guidelines upon which reform could be effected? The Reformers, including Calvin, were convinced that God’s Word and that alone was to be the standard for reform. But, Calvin rightly knew – as did his fellow Reformers – that the Bible ‘seriously affects us only when it is sealed upon our hearts through the Spirit’ (Institutes 1.7.5).

From the mouth of God

Contrary to the position of the Roman Church which sought to put itself in authorityover the Word of God, Calvin desired above all else to live under its authority. That authority is ultimately based on the fact that the Bible is from God. Moreover, only the inner testimony that the Spirit gives can persuade men of this fact. In Calvin’s words, as he drew this discussion to a close: ‘we affirm with utter certainty (just as if we were gazing upon the majesty of God himself) that it [i.e. the Bible] has flowed to us from the very mouth of God by the ministry of men. We seek no proofs, no marks of genuineness upon which our judgment may lean; but we subject our judgment and wit to it as to a thing far beyond any guesswork’ (Institutes 1.7.5).