In the early stages of the ‘Fundamentalist-modernist controversy’, John Gresham Machen (1881-1937), then Professor of New Testament Literature and Exegesis at Princeton Theological Seminary, set this struggle in the overall framework of church history.

The struggle, he noted, ‘is one of three great crises in the history of the Christian church. One came in the second century when Christianity was almost engulfed by paganism in the church in the form of Gnosticism. There was another in the Middle Ages when legalism was almost dominant in the church, similar to the modern legalism which appears in the liberal church. Christianity today is fighting a [third] great battle, but I, for my part, am looking for ultimate victory. God will not desert His church’.

This third ‘great battle’ had erupted in 1922 within the ranks of his ecclesial community, Northern Presbyterianism. Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878-1969), a liberal Baptist minister, had trumpeted the question from the pulpit of the First Presbyterian Church in New York, ‘Shall the Fundamentalists win?’ Machen’s answer, as he looked at the church’s victory in the previous ‘great crises’ of her history, was an unequivocal ‘yes’.

Machen’s confidence in a sovereign God, the Lord of history, is abundantly evident. But before pursuing Machen’s thoughts about the importance of history in relationship to Christianity, let us see how God led him to become a defender of the faith.

Machen’s early years

John Gresham Machen was born in 1881 in Baltimore, Maryland, which in those days stood at the crossroads of Northern and Southern life. His parents were firm supporters of the South, and gave their son not only the mores of Southern culture, but also the robust Calvinist spirituality of Southern Presbyterianism. As a young boy he was taught the Westminster Shorter Catechism which, by his teen years, had given him a good command of the riches of Scripture and Reformed doctrine.

In 1898, Machen went to John Hopkins University in Baltimore, graduating three years later with a BA degree in classics. At the urging of his pastor, Harris E. Kirk, he went on to Princeton Seminary in 1902, though at the time he had no intention of entering a vocational ministry. Princeton was renowned as ‘a Gibraltar of orthodoxy’, her faculty justly proud of the school’s unwavering faithfulness to the core of Reformation theology. Since the founding of the seminary in 1812, a noteworthy line of theologians had laboured there, among them Archibald Alexander (1772-1851), Charles Hodge (1797-1878), Archibald Alexander Hodge (1823-1886) and Benjamin B. Warfield (1851-1921). These men had, in the words of American historian Mark Noll, ‘upheld Reformed confessionalism, …defended high views of biblical inspiration and authority … and … had a surprisingly large place for the role of the Holy Spirit in religious experience’.

Shaken to the core

Three years of study at the seminary gave Machen skill as a biblical exegete, particularly with regard to the New Testament, but still no clear direction as to his future. In his final year of study he won a fellowship in New Testament studies which encouraged him to think of spending a year abroad, honing his abilities as a scholar. He decided to spend the academic year of 1905-1906 in Germany studying with a number of well-known New Testament scholars, of whom the chief was Johann Wilhelm Herrmann (1846-1922). Sitting at the feet of these men, Machen was exposed to the full force of liberalism. Although he had had religious doubts before he ever set foot in Europe, his experience in Germany shook his faith to the core.

The liberalism of Wilhelm Herrmann

Of all the scholars whom Machen heard lecture during this time in Germany, none impressed him so much as Herrmann. Hardly known today, Herrmann was at that time probably the leading liberal theologian in Europe. Two of those who would become well-known figures of twentieth-century theology, Rudolf Bultmann and Karl Barth, were among his students. As a lecturer, he was captivating. Machen was certainly not ignorant of specific flaws in Herrmann’s theology, yet he confessed in a letter to his father that his chief feeling with respect to Herrmann was ‘one of the deepest reverence’.

Herrmann was convinced that as a person reads the New Testament, the love and moral seriousness that characterised the inner life of Christ shines through its pages, impacting the reader and transforming his or her life. True faith, he claimed, is rooted in this encounter with the inner life of Christ, as it is portrayed in the New Testament. The truth, or falsity, of the historical details of Christ’s external life were of little significance for the German liberal.

Herrmann actually argued that the events of Christ’s life and ministry are shrouded in myth. Nevertheless, he believed that the power of Jesus’ inner life broke through all the veils of mythology and tradition, giving the believer a firmer ground of faith than the Apostles’ witness to the resurrection of Jesus!

Resolving doubts

Machen’s traumatic first-hand encounter with German liberalism came to a close in the summer of 1907 when he accepted a one-year appointment at Princeton as an instructor in New Testament. The invitation to return to Princeton may well have been a concerted effort on the part of the faculty to rescue Machen from the clutches of liberalism. Machen seriously contemplated returning to Germany at the conclusion of that academic year, but happily his career became increasingly entwined with the halls of Princeton. He stayed on, teaching the New Testament, seeking to resolve the doubts that plagued him. Slowly, he yielded to scriptural truth and the winsome influence of his colleagues, of whom the chief was Benjamin Warfield. By the time that he was formally installed as Assistant Professor of New Testament in 1915, and gave his inaugural address on ‘History and faith’, he had firmly embraced the Princeton tradition.

History and faith (1915)

His inaugural address makes it abundantly clear that the clouds had lifted and Machen had resolved the doubts that had bedevilled him ever since his time in Germany. ‘History and faith’ is thus a public reply to Herrmann and the liberal perspective on history and the reliability of Scripture.

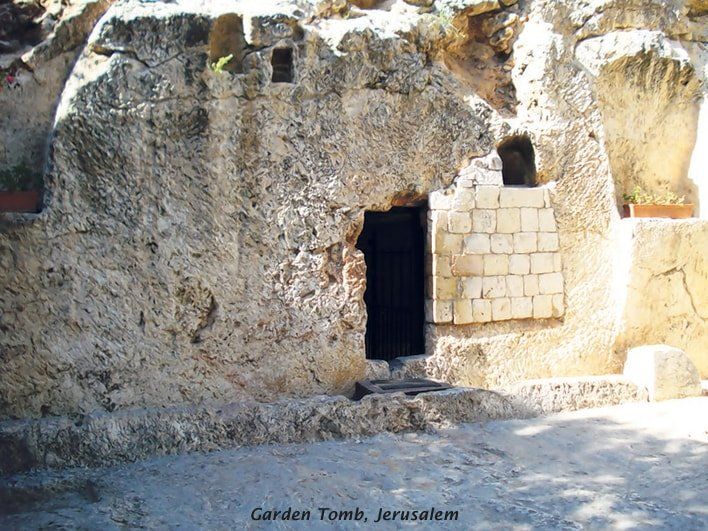

Machen begins with the basic assertion that a ‘gospel independent of history is simply a contradiction in terms’. Biblical faith and history are inextricably yoked together. For instance, in the Bible’s account of the life, ministry, death and resurrection of Christ, various historical assertions are made. He is said to have been born of a Virgin; to have lived ‘a life of perfect purity, of awful righteousness, and of gracious, sovereign power’. According to Scripture, his death is never viewed as a ‘mere holy martyrdom’ – a common assertion in early twentieth-century liberal circles – but as ‘a sacrifice for the sins of the world’. He was resurrected bodily, which was ‘a mighty act of God’ and a fact of history, not ‘a vision, an hallucination’, as some liberals asserted. Christ is still alive ‘in mysterious union with the eternal God’, and ever ready to help those who turn to him. This composite picture drawn from the Pauline epistles and the four Gospels is, Machen asserts, the portrayal of nothing less than ‘a supernatural Person’.

The supernatural Jesus

Liberal scholars, however, seeking to retool Christianity to fit the naturalistic viewpoint of the day, wanted nothing to do with a supernatural Jesus. They felt that ancient ideas about God, and his supernatural intervention in the world, had little to say to the men and women of twentieth-century urban culture. They thus attempted to separate the natural from the supernatural in the New Testament, and so ‘disentangle the human Jesus’ from a divinity thrust upon him by the early church.

But, as Machen points out, the ‘supernatural Jesus is the only Jesus that we know’. The scriptural record simply does not give us liberty to separate the divine from the human in the life of Christ. The ‘divine and human are too closely interwoven’. ‘Reject the divine’, asserts Machen and, ultimately, ‘you must reject the human too’.

Consider, Machen continues, the beginning of the Christian movement. What is to account for it? During his life and earthly ministry Christ had won ‘comparatively few’ disciples. Left to their own resources, these disciples can hardly be credited with beginning what we know as Christianity. They were ‘far inferior’ to Christ ‘in spiritual discernment and in courage’. They had not the ‘slightest trace of originality’. They had been ‘abjectly dependent upon the Master’ during his earthly life and, moreover, had never ‘succeeded in understanding Him’. ‘What little understanding, what little courage’ they did possess evaporated after his death. ‘How could such men’, Machen asks, ‘institute the mightiest religious movement in the history of the world?’

Simply looking at the historical record, it is obvious that something extraordinary must have happened between the death of Christ and the bold preaching of the first disciples. Scripture explains the transformation by the physical resurrection of Christ. Machen puts it thus: ‘History is relentlessly plain. The foundation of the Church is either inexplicable, or else it is to be explained by the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. But if the resurrection be accepted, then the lofty claims of Jesus are substantiated; Jesus then was no mere man, but God and man, God come in the flesh’.

The presence of Christ

The liberal ‘remake’ of Christianity emphasised Christian experience at the expense of historical truth. We saw that much in the theology of Wilhelm Herrmann. Machen tended to respond to this distortion of biblical Christianity by focusing on the historical and logical truth of the Christian faith. But he was not oblivious to the necessity of spiritual experience. Thus, as he brought his address to its close, he declared: ‘An historical conviction of the resurrection of Jesus is not the end of faith but only the beginning; if faith stops there, it will probably never stand the fires of criticism. We are told that Jesus rose from the dead; the message is supported by a singular weight of evidence. But it is not just a message remote from us; it concerns not merely the past. If Jesus rose from the dead, as He is declared to have done in the Gospels, then He is still alive, and if He is still alive, then he may still be found. He is present with us today to help us if we will but turn to Him. …Christian experience cannot do without history, but it adds to history that directness, that immediateness, that intimacy of conviction which delivers us from fear’.

The historicity of the resurrection is substantiated as men and women trust in the message that Christ is risen from the dead, and find that their trust is not misplaced. Machen was thus very conscious of the fact that there is a subjective side to the Christian life.

Significance for today

Machen’s defence of Christianity in his 1915 address was but the first of a number of publications which argued that Christianity was a historically verifiable, doctrinally rooted faith. He rightly saw that biblical Christianity involves a number of vital truths that are inextricably interwoven: God has revealed himself in history – primarily in the incarnation, death and resurrection of Christ. Men and women have access to this revelation in the Scriptures, and the Christian faith is rooted in these specific historical events. As Paul declared in 1 Corinthians 15:17: ‘If Christ is not risen, your faith is futile’.

Machen well knew that Christianity is more than history. As he told the Scottish Free Church Assembly in 1927, ‘we must know Christianity in our inner lives’. But if the historical affirmations of the Bible are not true, if they are errant accounts clothing inerrant truth, or if (as is commonly affirmed by radical ‘deconstructionists’ today) we have no access to these historical events, then Christianity is sunk without trace.

Recycling old errors

It is important to recognise that this issue is not merely of antiquarian interest. Some contemporary Evangelicals seem bent on reproducing the errors of those whom Machen so ably opposed. John Goldingay, principal of St John’s Theological College in Nottingham, England, and a professing Evangelical, has recently criticised the high doctrine of Scripture evidenced in the Princeton tradition.

Warfield, in particular, is taken to task for affirming the factual and historical inerrancy of Scripture. Goldingay believes that while the Bible is wrong in some of its historical and scientific details, on the whole it is ‘quite reliable’. The assertion that the Bible is inerrant is only accurate, he claims, in matters dealing with salvation. To be sure, Goldingay’s position is not a full-blown endorsement of Herrmann or Harnack, who taught that the historical narrative of Scripture is riddled with myth and error. But the difference appears to be one of degree and not of kind.

A new Reformation

As Machen reflected on the way the liberalism of his day obscured the gospel, he longed for a ‘new Reformation’, a time when the gospel would ‘come forth again to bring light and liberty to mankind’; a time when ‘those upon whom God has laid His hand, to whom the gospel has become a burning fire within them … speak the word that God has given them and trust for the results to Him alone’. When such a time came, it would ‘not be the work of men but the work of the Spirit of God’. Nevertheless, he was convinced that such a reformation ‘will be prepared for … not by the concealment of issues, but by clear presentation of them; not by peace in the Church between Christian and anti-Christian forces, but by earnest discussion; not by darkness, but by the light’. May we, by God’s grace, share both this longing and this conviction.