What is evangelicalism? What distinguishes those who call themselves evangelicals from other professing Christians? As we come to the end of this century and millennium, these questions of identity are among the most vital facing the evangelical movement, for it is increasingly unclear what is meant by the terms ‘evangelical’ and ‘evangelicalism’. Scottish theologian A.T. B. McGowan has rightly noted of the present scene: ‘The word “evangelical” has become so elastic today as to defy definition at all’.

Answering the question

Now, one way of answering these questions would be along the pathway of etymology. The English terms ‘evangelicalism’ and ‘evangelical’ would be traced back to their origin from the Greek word, euangellion, which can be translated either as ‘gospel’ or ‘good news’. By this route one could arrive at a description of evangelicals as people who are concerned with the gospel. But this approach leaves far too much unsaid.

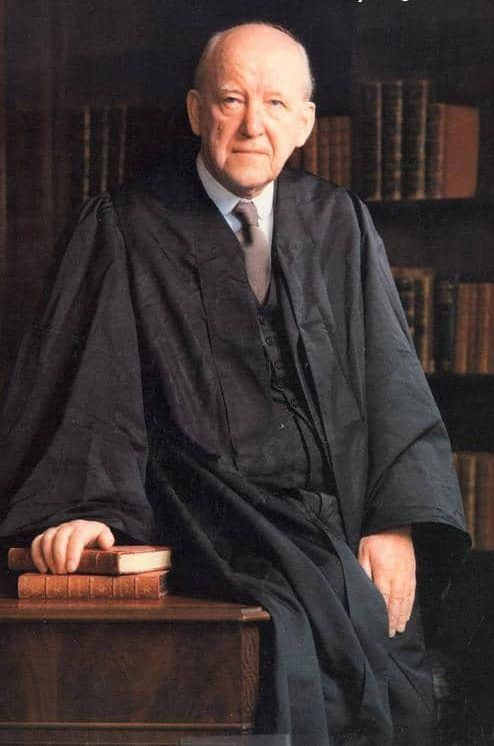

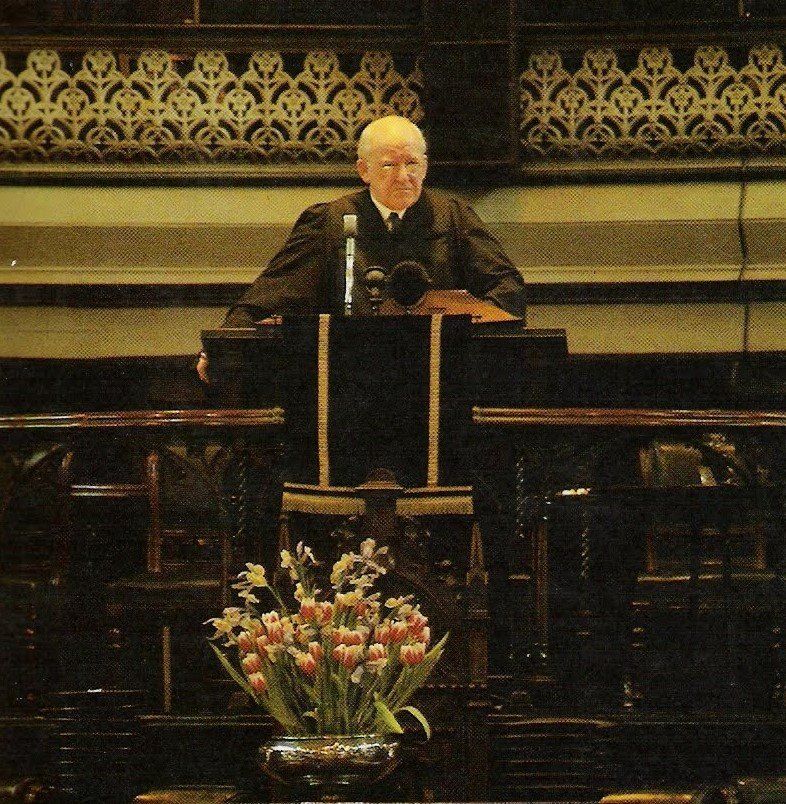

Alternatively, one could look at the broad sweep of evangelical history, from its roots in the Reformation and Puritanism down to the present day, and identify various defining characteristics. A third approach, however, is to look at this matter of defining evangelicalism by examining the thought of a single evangelical, one who has reflected deeply on the nature of evangelicalism, both in terms of its scriptural basis and its historical witness. D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899-1981) was such an evangelical.

Deeply involved in defending the evangelical vision of the Christian life for much of his career, he pondered deeply, from the vantage-point of both Scripture and church history, the issues surrounding this question, ‘What is an evangelical?’ Indeed, in the final fifteen years of his life he became involved in a major controversy over these issues.

Life and ministry

The broad outlines of Martyn Lloyd-Jones’ life are familiar to many readers of this newspaper. Born in Cardiff, Wales, on 20 December 1899, his earliest experiences of church life were in the Presbyterian Church of Wales, heir to the evangelical theology and fervent piety of Calvinistic Methodism. Sadly, by Lloyd-Jones’ day, the evangelical fervour and spirituality of the denomination had largely fallen prey to liberal theology. Instead of Calvinism’s rich and majestic vision of a sovereign God rescuing fallen human beings through the atoning work of his Son, Lloyd-Jones was raised on a tepid diet of faith in social betterment through education and political action.

In his early teens his family moved to London. There, during the momentous days of World War I, he enrolled as a student at the medical school of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, from where he received his MRCS and LRCP in July 1921, and later his Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MB, BS.) and M.D. For the next three years, Lloyd-Jones worked closely with the physician to the royal family, Sir Thomas (later Lord) Horder (1871-1955), first as his junior house physician, then as his chief clinical assistant.

Conversion and call

Despite this dazzling rise to prominence in the medical world, Lloyd-Jones was having serious doubts about continuing in his chosen profession. In the words of his grandson, Christopher Catherwood, Lloyd-Jones was ‘struck by the ungodliness and moral emptiness of many of Horder’s aristocratic patients’. He became convinced that the root problem of many of his mentor’s clients was ultimately spiritual. They were seeking to live out their lives with no conscious relationship to the One who had created them and who sustained them every moment of their lives. Their need, though, highlighted his own need for such a relationship.

Lloyd-Jones’ conversion, which he never dated, took place at some point in 1923 or 1924. With it, came a call and a passion to preach the gospel in his native Wales. At the end of 1926, he accepted a call to pastor Bethlehem Forward Movement Mission, a Calvinistic Methodist work in Sandfields, Aberavon. A few weeks later, on 8 January 1927, he married Bethan Phillips, also a medical doctor. Martyn and Bethan had a singularly happy life together. According to their grandson Christopher, they ‘complemented each other and were able to strengthen each other’ throughout their married lives.

Crucial move

By the mid-1930s, Lloyd-Jones’ preaching had made him known throughout England and Wales. It was characterised by a warm and vigorous Calvinism, a commitment to the ‘vital spirituality of eighteenth-century Methodism’, and a concern for the work of the Holy Spirit in regeneration and revival.

So it was that he came to the attention of G. Campbell Morgan (1863-1945), the well-known minister of Westminster Chapel in London. Hearing Lloyd-Jones preach in Philadelphia in 1937, Morgan determined to have the Welsh preacher called as his assistant. Lloyd-Jones went to Westminster on the eve of World War II. As he would tell his biographer Iain Murray, not long before his death, his life had witnessed a succession of events that he himself had never expected or planned. His move to Westminster Chapel was certainly one of them. It turned out to be a crucial move. Located in the heart of London, he was placed in a position to exercise a far greater influence on English-speaking evangelicalism than would have been possible had he remained in Wales.

Rebuilding

Lloyd-Jones served as Morgan’s associate pastor until the latter’s retirement in 1943. Lloyd-Jones was then the sole preaching pastor until his own retirement in 1968. The war scattered most of the large congregation that had delighted in Morgan’s preaching. Thus, when the war was over, Lloyd-Jones had to rebuild the congregation from around one or two hundred. By the 1950s, attendance was often close to two thousand. What drew these people was the clarity of biblical exposition, the spiritual power, and the doctrinal depth of Lloyd-Jones’ ministry.

Divisions within evangelicalism

Lloyd-Jones’ biographer Iain Murray has described the 1960s as ‘the hardest decade’ in the Welsh preacher’s life. It saw the break-up of some old friendships that he had treasured for many years, most notably his close working relationship with the Anglican evangelical J. I. Packer (b.1925).

Without going into all the historical details of the controversy within English evangelical circles between 1960 and 1970, it is sufficient to note that Lloyd-Jones clearly discerned a serious division within evangelicalism. Some evangelicals, like Packer, were quite willing to stay within denominations where liberal teachers and outright heretics were tolerated. Their hope was that by doing so they could ultimately win the denomination to a firmly evangelical position.

Lloyd-Jones disagreed profoundly. ‘We have evidence before our very eyes’, he said to those gathered for the Puritan Conference in December 1965, ‘that our staying amongst such people does not seem to be converting them to our view, but rather leads to a lowering of the spiritual temperature of those who are staying amongst them, and an increasing tendency to doctrinal accommodation and compromise’. It was in the context of this debate and controversy that Lloyd-Jones went back to Scripture to determine the nature of genuine Christian unity.

Closer fellowship

The differences that Lloyd-Jones perceived within evangelicalism were brought out fully into the open in 1966 when, on 18 October, he addressed the second National Assembly of Evangelicals, a meeting organised by the Evangelical Alliance. He urged evangelicals in theologically-mixed denominations to recognise that staying in such organisations made them guilty of schism from other, genuine, believers, who were in solidly biblical churches. They should come out of doctrinally-compromised bodies to enjoy closer fellowship with their evangelical brethren. Only then, he said as he concluded, could they expect the blessing of the ‘Spirit of God to come upon us in mighty revival and re-awakening’.

Contradicted

John Stott (b.1921), the well-known Anglican Evangelical preacher who was chairing the meeting that autumn evening, quickly rose when Lloyd-Jones had concluded his address. Perhaps fearful lest some young evangel-icals in mixed denominations might pull out on the spur of the moment without serious thought, he flatly contradicted everything that Lloyd-Jones had said. ‘History’, he declared, ‘is against what Dr Lloyd-Jones has said…Scripture is against him; the remnant was within the church not outside it. I hope no one will act precipitately’.

Not surprisingly, Stott’s dramatic intervention highlighted and consolidated the deep differences that existed among evangelicals at that time. Those differences have continued ever since to polarise the British evangelical community.