In his autobiography, the British soldier and novelist John Masters recalls a church service held during the Burma campaign in World War II. The chaplain recounted the weeks of fierce fighting they had endured behind the Japanese lines.

He declared that the hand of God had been with them, notwithstanding the privations and losses they had experienced. He then called the Brigadier to say a few words. Masters rose to speak, wondering what to say. As he stood up, he noticed that there were groups of armed sentries ‘in a peculiarly formalised position of alert’ at the points of the compass around the assembly.

Then he recalled that one of his units was the 1st Battalion, the Cameronians (The Scottish Rifles). They had been raised 250 years before by the Covenanters in support of King William III and the Glorious Revolution. Ever since then, they had posted sentries at their church parades in memory of the field meetings (or conventicles) held during the times of persecution in seventeenth century Scotland.

‘What was I to say to them?’ Masters asked himself. ‘The hand of God? Causing death and mutilation, taking sides in violence? Not the Christian God, surely’. So he just thanked them for their courage and sat down.

God’s hand in everything

Is that it, then? Is there no ‘hand of God’ in the tough times of life? Does the ‘Christian God’ have no role in the visitation of war and pestilence on a sinful world? Is he only a purveyor of palliatives, a dispenser of sweet blessings? Meanwhile we just have to grit our teeth and bear it?

This was surely not the outlook of the original Cameronians, as their sentries watched for the dragoons in those desperate days so long ago. What they understood (and what the Bible makes very clear) is that God does have a hand in the bad things as well as the good. If we can grasp this truth it will encourage us to look to the Lord, all the more, in the midst of hard experiences.

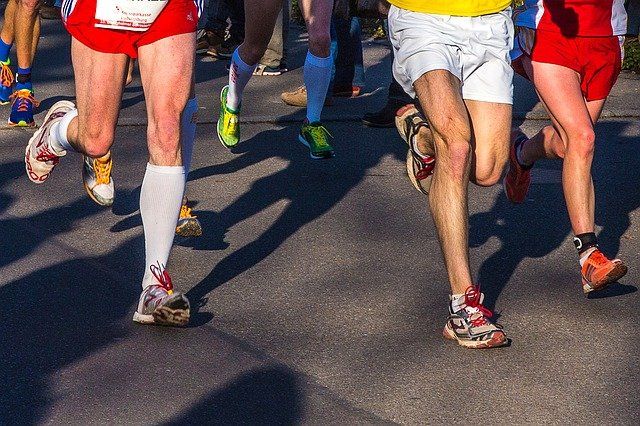

In Hebrews 11- 12, having reviewed the troubles of the faithful followers of God, the writer exhorts us to ‘run the race with endurance … looking unto Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith’, and to ‘consider him who endured such hostility of sinners against himself, lest you become weary and discouraged in your souls’ (Hebrews 12:1-3).

He points out that, unlike Jesus, his readers had ‘not yet resisted to bloodshed, striving against sin’ (12:4) and then quotes Proverbs 3:12: ‘For whom the Lord loves he chastens, and scourges every son whom he receives’.

God means it for good

These references surely reminded the readers that Jesus, ‘though he was a Son, learned obedience in the things that he suffered’ (Hebrews 5:8). Great evils were done to Jesus, and great evils still happen to God’s people today.

But the words of Joseph to his brothers provide a wider and more encouraging perspective on our sufferings: ‘You meant evil against me; but God meant it for good, in order to bring it about as it is this day, to save many people alive’ (Genesis 50:20). This reminds us that God’s love will be as evident to the eye of faith in affliction as in abounding blessing.

Hebrews 12:5-11 teaches us that all afflictions that befall the believer, from mere irritations to crushing evils, are transformed into discipline, bringing victory from defeat and giving ‘beauty for ashes, the oil of joy for mourning, the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness’ (Isaiah 61:3).

Notice that discipline achieves two main ends: it proves God’s love for us (vv. 4-8) and it improves our love for God (vv. 9-11).

God’s love for us

Hard experiences are often hard to interpret. This is specially true if you think that being a Christian or a generally decent type ought to render you immune to such things.

It is never easy to cope with the ‘bad things’ that happen in life, but it is made much more difficult if you forget Solomon’s dictum that ‘All things come alike to all: one event happens to the righteous and the wicked; to the good, the clean, and the unclean; to him who sacrifices and him who does not sacrifice. As is the good, so is the sinner; he who takes an oath as he who fears an oath’ (Ecclesiastes 9:2).

No one relishes the hard knocks of life. We all want things to go well all of the time. How, then, are we to deal with illnesses, bereavements, career setbacks, errors of judgement, disasters, criminality, persecution and the like? Are these just what people call ‘the breaks’ of life, ‘the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’?

If so, they raise serious questions about the love of God and are prima facie evidence that he is not in control of events. When bad things happen to God’s people, does it mean that God no longer covers his own by a gracious providence, or is incapable of doing so? For an answer, the writer points to Proverbs 3:11-12. Thinking particularly of ‘hostility from sinners’ (v. 3), he asks if they had ‘forgotten’ Solomon’s exhortation: ‘My son, do not despise the chastening of the Lord, nor be discouraged when you are rebuked by him; For whom the Lord loves he chastens, and scourges every son whom he receives’ (vv. 5-6).

Fatherly care

John Chrysostom applies this to our doubts: ‘See it is those very things in which they suppose they have been deserted by God that should make them confident that they have not been deserted’.

The argument is this: if we believe God and love him as our heavenly Father, we must also believe that he loves us. Then we can understand that the ‘bad things’ we suffer, whatever their immediate source, are both the evidence and the arena of the outworking of his fatherly care toward us.

To be angry at God because he has not shielded us from these things, misses the point, and we fail to learn the lesson they are designed to teach. If we belong to Jesus Christ, we can expect chastening through hard experiences. This arises from love, not neglect, and points us to the Fatherhood of God towards those who have believed on his Son.

We need discipline

This really offends some folk. Even Christians often expect nothing but abounding blessings in their lives, just because they are believers. They cannot think of any reason why God would chastise them in any noticeably distressing way.

Look at Psalm 89:27-33: ‘I will make him my firstborn, the highest of the kings of the earth. My mercy I will keep for him forever and my covenant shall stand firm with him. His seed also I will make to endure forever, and his throne as the days of heaven. If his sons forsake my law and do not walk in my judgments, if they break my statutes and do not keep my commandments, then I will punish their transgression with the rod, and their iniquity with stripes. Nevertheless my lovingkindness I will not utterly take from him, nor allow my faithfulness to fail’.

Notice five very practical truths in these verses.

1. The ‘firstborn’ (v. 27) is Jesus, even though he is referred to in verse 20 as ‘My servant David’. This is a prophetic reference to the Messiah.

2. We are told that ‘his sons’ (believers) do ‘forsake’ God’s law. Everyone sins, even the most godly of God’s people (v. 30).

3. They commit ‘transgression’ and ‘iniquity’. We are not talking about what people today lightly excuse as their ‘mistakes’ (which are sins anyway). Even saved sinners are serious sinners when they sin (v. 32).

4. God responds to this with ‘rod’ and ‘stripes’, that is, painful experiences (also v. 32).

5. Yet God does not take his ‘lovingkindness’ from them ‘utterly’; there is a silver lining in these clouds (v. 33).

Heart of the matter

This little package of biblical teaching takes us to the heart of the matter. For one thing it explains why John Master’s imagined ‘Christian God’ could never be party to the violence in World War II. It was because John Masters did not grasp the true holiness of the real Christian God and the sinfulness of sin. Still less did he understand the lovingkindness of the Saviour in his dealings with the human race.

Positively, we can say that when we do grasp these truths, then (and only then) does the teaching of Hebrews 12 come alive. Our afflictions begin to make sense precisely because our Father God is watching out for us.