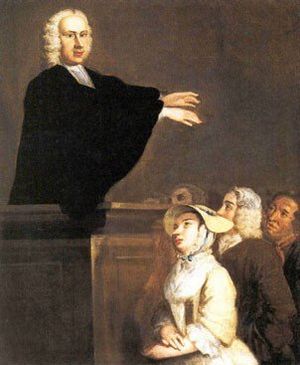

In the two previous articles we have considered the spirituality of that remarkable man of God, the eighteenth-century evangelist George Whitefield (1714-1770). It is calculated that he preached around 18,000 sermons in the thirty-five years between his conversion in Oxford in 1735 and his death in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1770. That works out at 514 sermons a year! Moreover, many of his sermons were delivered to congregations that numbered 10,000 or so, and some to audiences possibly as large as 20,000.

His preaching was used to bring about the conversion of tens of thousands of people. Here is the story of one such individual, Robert Robinson (1735-1790), and a hymn he wrote entitled ‘Come, thou fount of every blessing’. It is a powerful celebration of God’s tremendous grace.

A teenage lark

When Robert Robinson first went to hear Whitefield, his motivation was an odd one, to say the least. On Sunday morning 24 May 1752, he and some friends were out looking for amusement. They came across an aged woman who claimed to be a fortune-teller.

After they had got her thoroughly drunk, they had her tell their fortunes. When it came to Robinson, the woman predicted that he would live to see his children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren growing up around him.

Now, what had started as a lark was taken quite seriously by Robinson as he made his way home. He thought that if he were indeed to live to such a ripe age, he would probably end up being a burden to his family. There were in those days no such things as social security or welfare. What could he do?

Well, he thought, one way for the aged to make themselves liked by their grandchildren is to have a good stock of stories with which to entertain them. He determined there and then to fill his mind with knowledge and ‘everything that is rare and wonderful’. When he was old, he reasoned, this would stand him in good stead and cause him, to ‘be respected rather than neglected’.

As his first acquisition, he decided to experience one of Whitefield’s sermons. He went to hear him, though, as he later told the famous preacher, he did so with abhorrence for Whitefield’s doctrine and feelings of pity for ‘the folly of the preacher’ and ‘the infatuation of the hearers’.

Haunted

Whitefield was preaching that evening at the Tabernacle, his meeting-house in Moorfields, London. His text was Matthew 3:7, John the Baptist’s stern rebuke to the Pharisees and the Sadducees: ‘O generation of vipers, who hath warned you to flee from the wrath to come?’

Robinson himself takes up the story. ‘Mr Whitefield described the Sadducean character; this did not touch me, [for] I thought myself as good a Christian as any man in England. From this he went to that of the Pharisees. He described their exterior decency, but observed that the poison of the viper rankled in their hearts. This rather shook me. At length, in the course of his sermon, he abruptly broke off; paused for a few moments; then burst into a flood of tears; lifted up his hands and eyes, and exclaimed, “O my hearers! the wrath’s to come, the wrath’s to come!” These words sunk into my heart like lead in the waters. I wept, and when the sermon was ended, retired alone. For days and weeks I could think of little else. Those awful words would follow me, wherever I went, “The wrath’s to come, the wrath’s to come!”’

For over three years Robinson was haunted by Whitefield’s sermon. He regularly attended the preaching at the Tabernacle, and found himself ‘cut down for sin’ and ‘groaning for deliverance’. Eventually, on Tuesday 10 December 1755, ‘after having tasted the pains of rebirth’, Robinson ‘found full and free forgiveness through the precious blood of Jesus Christ’.

About two and a half years after his conversion Robinson wrote a hymn which has become very well known: ‘Come, thou fount of every blessing’. It commemorates what God had done for him when he saved him.

The fount of blessing

Come, thou fount of every blessing,

Tune my heart to sing thy grace;

Streams of mercy, never ceasing,

Call for songs of loudest praise.

Teach me some melodious sonnet,

Sung by flaming tongues above.

Praise the mount! I’m fixed upon it,

Mount of thy redeeming love.

The opening line is drawn from Jeremiah 2:13. There, the Lord upbraids his people for forsaking him, ‘the fountain of living waters’, and living instead on the water drawn from ‘broken cisterns’ of their own making.

Just as a fountain continually bubbles up to nourish those who partake of it, so God’s providence daily overflows with blessings, ‘streams of mercy, never ceasing’, for his children. The proper response to such lavish bestowal of grace is praise and adoration.

So, Robinson asks God to ‘tune’ his heart to sing God’s grace and, to that end, to teach him ‘some melodious sonnet’. Believers need grace to praise God properly for what he has done in their lives by that same grace!

What should be the special focus of this praise? Nothing other than the cross of Christ, which Robinson calls the ‘mount of thy redeeming love’. Why such a focus on the cross in worship? Because there God’s love for sinners is most powerfully revealed. Nothing compelled Christ to suffer for sinners except his love for them. No wonder Robinson declares that he is ‘fixed’ upon the cross, determined never to be moved from it.

An earlier version of the hymn appeared in a 1774 hymnal used by congregations associated with Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. The title-page of this hymnal bears the following inscription. ‘The Cross of Christ is the Key to Paradise; the weak Man’s Staff; the Convert’s Convoy; the upright Man’s Perfection; the Soul and Body’s Health; the Prevention of all Evil; and the Procurer of all Good’.

The Lord our helper

Here I raise my Ebenezer;

Hither by thy grace I’ve come;

And I hope, by thy good pleasure,

Safely to arrive at home.

Jesus sought me when a stranger,

Wandering from the fold of God;

He, to rescue me from danger,

Interposed his precious blood.

The second stanza opens with an allusion that may not be immediately familiar. It is a reference to 1 Samuel 7:12, where Samuel, after routing the Philistine army, took a stone and ‘set it between Mizpah and Shen, and called the name of it Ebenezer, saying, “Hitherto hath the Lord helped us”’.

Robinson raised a spiritual Ebenezer to commemorate God’s victory over Satan in his own life. For it was only by God’s help that he had been saved, and it was solely due to God’s grace that he had come thus far in his Christian walk.

It is only by God’s grace that any of us ever begin the Christian life. We were all strangers to that grace (see Ephesians 2:11-12), wandering aimlessly in the world. But God sent Jesus Christ to rescue us from eternal danger, the punishment rightfully due to us as sinners. Jesus stood in our place and suffered God’s wrath, that he might rescue his chosen ones from an eternity of misery and woe. He ‘interposed his precious blood’ (Ephesians 2:13; 1 Peter 1:18-19).

Our debt to grace

Oh! to grace how great a debtor

Daily I’m constrained to be!

Let thy goodness, like a fetter,

Bind my wandering heart to thee.

Prone to wander, Lord, I feel it,

Prone to leave the God I love;

Here’s my heart, O take and seal it,

Seal it for thy courts above.

But our debt to God’s grace does not end with the life-changing event that turns sinners into saints. We are debtors also to his keeping grace that enables frail humans to remain true to their Lord. Grace surrounds the believer on every hand.

Despite all of this, there is a candid recognition by Robinson that his heart is ‘prone to wander’ and ‘to leave the God’ he loves. The believer’s greatest struggle lies not with the world or with Satan, but with indwelling sin and the unmortified elements of his life and heart. Only God’s grace can give victory here. Thus, Robinson commits himself afresh to the mercies of God: ‘Here’s my heart, O take and seal it; Seal it for thy courts above’.

We need God’s grace to begin the Christian life, but we also need it all the way through. As Robinson’s Baptist contemporary Abraham Booth put it: ‘Grace shines through the whole [of our salvation] … it is not like a fringe of gold, bordering the garment; not like an embroidery of gold, decorating the robe; but like the mercy-seat of the ancient tabernacle, which was gold — pure gold — all gold throughout’.