J. I. Packer has observed that a ‘revival … is always a disfigured work of God, and the more powerful the revival, the more scandalising disfigurements we may expect to see’. This was certainly the case in the American Great Awakening.

Between 1740 and 1742 it is estimated that there were as many as 40,000 conversions in New England alone. William Cooper (1694-1743), the assistant pastor of Brattle Street Church, Boston, declared that the entire face of the town had been changed.

Taverns and dancehalls were much less frequented than before. The Christian faith became a topic of regular and daily conversation in peoples’ homes. ‘The doctrines of grace’ were ‘espoused and relished’.

Private religious meetings multiplied greatly, and public worship was well attended with ‘attentive and serious’ hearers. ‘There is indeed’, Cooper emphasised, ‘an extraordinary appetite after “the sincere milk of the word”‘.

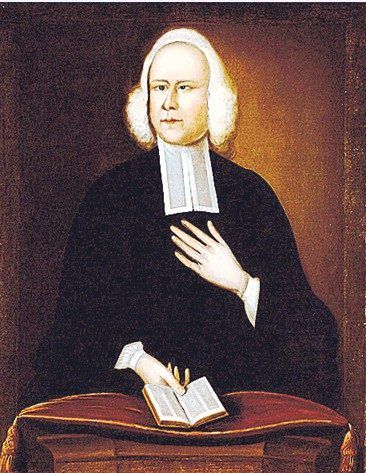

James Davenport

On the other hand, fanaticism (‘enthusiasm’ in 18th-century jargon) gripped more than a few in this revival. Chief among the ‘enthusiasts’ who troubled the revival in New England was James Davenport (1716-1757). Descended from a distinguished Puritan forebear, he pastored a Congregationalist church in Southhold, Long Island.

Davenport became acquainted with the great evangelist George Whitefield (1714-1770) in 1740 in New York and soon sought to imitate the success of the English preacher. Itinerating throughout New England, however, he was led into increasingly fanatical attitudes and patterns of behaviour.

When he came into a town he would interrogate the minister as to his spiritual state. Those who refused to answer his questions, or whose answers did not satisfy him, were declared unconverted and unfit to be spiritual leaders. He would then encourage the members of their congregations to forsake them and conduct their own meetings.

Invariably he would publicly upbraid those members of the clergy he deemed to be unconverted. For example, at New Haven, Connecticut, he branded the pastor Joseph Noyes ‘an unconverted hypocrite and the devil incarnate’. Not surprisingly, wherever Davenport went he left divided congregations in his wake.

Claims

Davenport – and others like him, such as his close friend, Andrew Croswell (1709-1785), the pastor of a Congregationalist church in Groton, Connecticut – began to assure individuals who fell to the ground, or experienced bodily tremors, or saw visions while they were preaching, that such experiences were a sure sign of the Spirit’s converting work.

In Croswell’s words, only those who have had such ‘divine manifestations … know what true Holiness means’. Croswell asserted that ‘God never works powerfully, but men cry out disorder; for God’s order differs vastly from their nice and delicate apprehensions’ of him.

Davenport, for his part, claimed to have the ability to distinguish who was among the elect of God. He especially sought to exercise this ‘gift’ when questioning the spiritual state of ministers who refused to let him preach from their pulpits.

A bizarre episode

The most bizarre episode of Davenport’s career took place on the afternoon of Sunday 6 March 1743, in the town of New London, Connecticut, where Davenport and his followers had established a seminary known as the ‘Shepherd’s Tent’.

Just as the inhabitants of the town were returning home from public worship, Davenport (under guidance ‘received from the Spirit in dreams’) directed his followers to publicly dissociate themselves from the ‘heresy’ of Puritan New England. They were to do so by burning in a bonfire a large quantity of Puritan tomes and folios.

Among the books burnt that day were said to be works by such well-known Puritans as John Flavel, Matthew Henry and Increase Mather, the father of Cotton Mather! Davenport’s followers then proceeded to dance around the bonfire praising God and shouting ‘Hallelujah’ and ‘Gloria Patri’ (Glory to the Father).

The following day Davenport and his followers prepared a second bonfire, this time intended to consume their own ‘idolatry’. Anything that smacked of the ‘world’ and worldly pride – ‘wigs, cloaks and breeches, hood, gowns, rings, jewels and necklaces’ – was heaped up, ready to be burned. Davenport himself stripped off his ‘breeches’ and hove them onto the pile.

Ammunition

At this point a bystander said to Davenport that he thought him demonised, to which the latter surprisingly agreed. Smitten with contrition for his actions, Davenport soon quit Connecticut for Long Island, a broken and shattered man.

Although Davenport would later confess that he had been wrong in much of what he had said and done, he had helped to spark a wildfire spirit that in many places made havoc of the revival.

Moreover, he had furnished anti-revival forces with ammunition for their attacks. These forces were captained by Charles Chauncy (1705-1787), nicknamed ‘old Brick’, the co-pastor of the most prestigious Congregationalist church in Boston. Chauncy declared Davenport to be ‘the wildest Enthusiast I ever saw’.

Chauncy had first written of the revival in 1741, when he actually gave thanks for what the Spirit of God was doing. He had no doubt that there were ‘a number in this land, upon whom God has graciously shed the influence of this blessed Spirit’, something for which, he and his readers (he said) should be thankful.

Yet he goes on to note some concerns. There have arisen ‘unchristian heats and animosities’ along with ‘rash, censorious, uncharitable judging’, and ‘evil speaking, reviling and slandering’ have become all too common. Here, Chauncy clearly had in view the uncharitable way that men like Davenport often treated those whom they judged to be unconverted.

Dictates of reason

By 1742, however, the prominent Boston pastor had become much more critical. In July of that year Davenport had appeared in Boston and specifically sought out Chauncy to pronounce judgement on the latter’s spirituality.

The encounter, which took place in the doorway of Chauncy’s study, decisively turned the latter against the revival. He quickly fired off a sermon, published as Enthusiasm Described and Cautioned Against. In it he accused Davenport and his ilk of being ‘enthusiasts’, who show their true colours by their blatant disregard of the ‘dictates of reason’.

In particular, Chauncy stresses that the arousal of ‘passions and affections’ needs to be carefully monitored. If the passions are set ablaze, but reason and understanding not enlightened, it is all to no avail.

Reason and judgement, the ‘more noble part’ of the human being, must be pre-eminent in all religious experience; otherwise it is but a sham and ‘enthusiasm’. Real religion, he concludes, is ‘a sober, calm, reasonable thing’.

Excesses

By the following month, Chauncy had penned a further attack on the revival in an open letter written to a minister in Scotland. Chauncy declares: ‘There never was such a spirit of superstition and enthusiasm reigning in the land before; never such gross disorders and barefaced affronts to common decency; never such scandalous reproaches on the Blessed Spirit, making him the author of the greatest irregularities and confusions’.

He is firmly persuaded that, in general, the revival is nothing more than the ‘effect of enthusiastic heat’.

For Chauncy, the excesses of the revival revealed its true nature; it was not at all a work of God’s Holy Spirit, but merely an instance of uncontrolled emotionalism. Viewing the revival through the lens of Davenport’s antics (and of others like him), it is not surprising that Chauncy came to the conclusion that the revival was mostly heat with little light, and should be rejected as spurious.

Chauncy saw the main work of the Spirit as the enlightenment of the mind. ‘An enlightened mind, and not raised affections’, he would later state, ‘ought always to be the guide of those who call themselves men; and this, in the affairs of religion, as well as other things: And it will be so, where God really works on their hearts by his Spirit’.

A middle way

Jonathan Edwards, one of the key leaders in the revival, thus found himself in the unenviable position of giving an answer to both sides in the debate about the nature of the revival.

To the ‘pious zealots’ like Davenport he will stress that biblical Christianity must involve the mind and reason. When God converts a person, light is shed upon the mind. On the other hand, there is much more to conversion than enlightenment.

In response to Chauncy and those of his persuasion, he will thus maintain that genuine spirituality flows from a heart aflame with the love of God. There is no genuine Christianity without a warm heart. The key work in which Edwards charted this middle way is A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections.

Harold P. Simonson, who has written a book presenting Edwards as a theologian of the heart, states that Edwards’ work was the culmination of ‘some twenty-five years of thought about the nature of religious experience’.

Iain Murray, in his marvellous biography of Edwards, can say that it ‘is unquestionably one of the most important books possessed by the Christian church on the nature of true religion’. And so it is, for in it we find an exhaustive and penetrating exposition of the nature of true Christian spirituality, a spirituality in which both heat and light are vital.