In 1994 the British Library paid well over two million dollars for a book which Dr Brian Lang, the chief executive of the library at the time, described as ‘certainly the most important acquisition in our 240-year history’. The book? A copy of the New Testament.

Of course, it was not just any copy. In fact, there is only one other New Testament like it in existence, and that one, which is in the library of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, is lacking seventy-one of its pages.

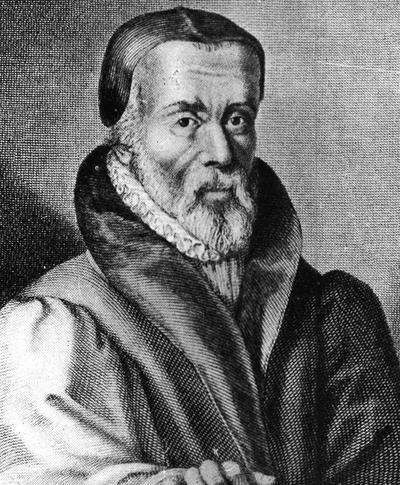

The New Testament that the British Museum purchased was lodged for many years in the library of the oldest Baptist seminary in the world, Bristol Baptist College. It was printed in the German town of Worms (pronounced ‘vorms’) on the press of Peter Schoeffer in 1526, and is known as the Tyndale New Testament. The first printed New Testament to be translated into English from the original Greek, it is indeed an invaluable book. Its translator, after whom it is named, was William Tyndale.

His overall significance in the history of the church is enormous. The article on him in the famous eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica rightly states that he was ‘one of the greatest forces of the English Reformation’, a man whose writings ‘helped to shape the thought of the Puritan party in England’.

Mother tongue

In strong contrast to medieval Roman Catholicism, where piety was focused on the proper performance of certain external rituals, Tyndale, like the rest of the Reformers, emphasised that faith lies at the heart of Christianity. But faith presupposes an understanding of what is believed. Knowledge of the Scriptures was, therefore, essential to Christian spirituality.

Thus, Tyndale could state: ‘I perceived by experience, how that it was impossible to establish the lay people in any truth, except the scripture were plainly laid before their eyes in their mother tongue’.

Tyndale’s determination to give the people of England the Word of God so gripped him that from the mid-1520s till his martyrdom in 1536 his life was directed to this sole end. What lay behind this single-minded vision was a particular view of God’s Word.

In the ‘Prologue’ to his translation of Genesis, which he wrote in 1530, Tyndale could state: ‘the Scripture is a light, and sheweth us the true way, both what to do and what to hope for; and a defence from all error, and a comfort in adversity that we despair not, and feareth us in prosperity that we sin not’.

Despite opposition from church authorities and the martyrdom of Tyndale in 1536, the Word of God became absolutely central to the English Reformation. As David Daniell has recently noted, in what has become the definitive biography of the Reformer, it was Tyndale’s translation that made the English people a ‘People of the Book’.

Major shift

The Reformation thus involved a major shift of emphasis in the cultivation of Christian spirituality. Medieval Roman Catholicism had majored on symbols and images as the means for cultivating spirituality. The Reformation, coming as it did hard on the heels of the invention of the printing press, turned back to the biblical emphasis on words (both spoken and written) as the primary vehicle of spirituality and, in particular, the words of the Bible.

Evangelicalism has always been strong when it has sought to cultivate a spirituality centred first and foremost in the Scriptures. Of course, we face challenges in this regard. There are those in our day who assert that words are no longer adequate. We need images and drama, they say. But this is nothing new. If we trace the history of Christian spirituality, we will find that those who assert a spirituality of the Word have frequently been criticised and subjected to verbal attack.

Consider, for instance, how the Puritan spirituality of the Word was challenged by radicals to their left. There were the Muggletonians, founded by Ludowicke Muggleton (1609-1698) and his cousin John Reeve (1608-1658), who believed that they were the two witnesses of Revelation 11:3-6. They denied the Trinity, rejected preaching and prayer, and argued that the revelation given to Muggleton and Reeve was God’s final word to mankind. Even more dangerous to the Puritan cause were the Quakers, in some ways the counterpart of the charismatic movement of the modern era.

Quakerism

The Quaker movement, which would become a major alternative to Puritanism, started in the late 1640s when George Fox (1624-1691), a shoemaker and part-time shepherd, and other early Quakers proclaimed the possibility of salvation for all humanity.

They urged men and women to turn to ‘the light within them’ to find salvation. We ‘call all men to look to the Light within their own consciences’, wrote Samuel Fisher (1605-1665), an Arminian Baptist turned Quaker. ‘By the leadings of that Light’, he continued, ‘they may come to God, and work out their Salvation’. Thus, when some Baptists in Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire became Quakers and declared that the ‘light in their consciences was the rule they desire to walk by’, rather than the Scriptures, they were simply expressing what was implicit in the entire Quaker movement.

Isaac Penington the Younger (1616-1679) is one early Quaker author who well illustrates this tendency to make the indwelling Spirit (rather than the Scriptures) the touchstone and final authority for thought and practice. Penington was born into a Puritan household and for a while was a Congregationalist. Converted to Quakerism in 1658, after hearing George Fox preach the previous year, Penington became an important figure in the movement.

In a letter to a fellow Quaker called Nathanael Stonar in 1670, Penington told his correspondent that one of the main differences between themselves and other ‘professors’, namely Calvinistic Puritans, was ‘concerning the rule [of life]’. While the Puritans asserted that the Scriptures were the rule by which people ought to direct their lives and thinking, Penington was convinced that the indwelling Spirit of life is ‘nearer and more powerful, than the words, or outward relations concerning those things in the Scriptures’.

Greater than the words?

Penington argued as follows. ‘The Lord, in the gospel state, hath promised to be present with his people; not as a wayfaring man, for a night, but to dwell in them and walk in them. Yea, if they be tempted and in danger of erring, they shall hear a voice behind them, saying, “This is the way, walk in it”. Will they not grant this to be a rule, as well as the Scriptures? Nay, is not this a more full direction to the heart, in that state, than it can pick to itself out of the Scriptures? … the Spirit, which gave forth the words, is greater than the words; therefore we cannot but prize Him himself, and set Him higher in our heart and thoughts, than the words which testify of Him, though they also are very sweet and precious to our taste’.

Penington here affirms that the Quakers esteemed the Scriptures as ‘sweet and precious’, but he was equally adamant that the indwelling Spirit was to be regarded as the supreme authority when it came to direction for Christian living and thinking.

In response to this threat to scriptural authority, and to a Bible-centred spirituality, the Puritans argued that the Spirit’s work in the authors of Scripture was unique and definitely a thing of the past. The Spirit was now illuminating that which he had once inspired, and all experiences of the Spirit were to be tested by the Scriptures.

The Spirit and the Word

As Richard Baxter (1615-1691) declared: ‘We must not try [i.e. test] the Scriptures by our most spiritual apprehensions, but our apprehensions by the Scriptures: that is, we must prefer the Spirit’s inspiring the apostles to indite the Scriptures, before [i.e. in preference to] the Spirit’s illuminating of us to understand them, or before any present inspirations, the former being the more perfect; because Christ gave the apostles the Spirit to deliver us infallibly his own commands, and to indite a rule for following ages: but he giveth us the Spirit but to understand and use that rule aright’.

From the Puritan point of view, the Quakers made an unbiblical cleavage between the Spirit and the Word. As another Puritan, the London Baptist Benjamin Keach (1640-1704), pointed out: ‘Many are confident they have the Spirit, Light, and Power, when ’tis all mere delusion. The Spirit always leads and directs according to the written Word: “He shall bring my Word,” saith Christ, “to your remembrance”’ (cf. John 14:26).

The Spirit’s witness

Lest it be thought that the Puritans, in their desire to safeguard a spirituality of the Word, went to the opposite extreme and depreciated the importance of the work of the Spirit in the Christian life, one needs to note the words of the Second London Confession (1.5). This states that, ‘our full persuasion and assurance of the infallible truth’ of the Scriptures comes neither from ‘the testimony of the Church of God’ nor from the ‘heavenliness of the matter [i.e. their content]’, the ‘efficacy of [their] Doctrine’, or ‘the Majesty of [their] Stile’. Rather, it is ‘the inward work of the Holy Spirit, bearing witness by and with the Word in our Hearts’ that alone convinces believers that God’s Word really is what it claims to be.

Puritan spirituality is thus a marvellous model for us today, a balanced spirituality of Word and Spirit.