We tend to assume that an Evangelical will remain constant in his beliefs, but history teaches us otherwise. We need to know not just what a man has believed in the past, but what he now thinks and believes.

Cardinals Manning and Newman, and William Wilberforce’s son, Robert, all started out as Evangelicals, but ended up far differently. It led to ‘the parting of friends’, and a similar process within Evangelicalism over the past fifty years has had like consequences. The story is faithfully unfolded by Iain Murray in Evangelicalism divided, probably the most important book he has yet written.

Colour change

The notable theological ‘weathercocks’ of this era have been Billy Graham, John Stott and J. I. Packer, none of whom could have envisaged how far they would turn. They have all acted from the best of motives, but their actions have had serious repercussions and led to regrettable divisions among Evangelicals. Others, too, have gone through a theological colour change in the heady climate of the ecumenical movement for church unity.

Many, who owe much to these men, can hardly believe that having begun so evangelically they should have changed so much. But Iain Murray gives us the documentary evidence, provided by quotations from their own lips and writings. He is at pains to do this, so that an accurate and fair account is presented.

Fifty years ago, Evangelicals in Britain were united on the gospel, and on what it meant to be a Christian. Co-operation and fellowship were maintained between Evangelicals of diverse denominational background, mainly by means of para-church movements.

Doctrinal thinking and expository preaching were almost non-existent in Evangelical circles, and there was a paucity of theological literature written from an evangelical standpoint. Rationalism and liberalism had taken a terrible toll of the churches. Mr Murray blames the influence of Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) for most of it.

Caught napping

With the launch of the World Council of Churches at Amsterdam in 1948, and the subsequent drive for church unity, Evangelicals were caught napping. Little thought had been given to the doctrine of the church or of church unity. Evangelicals began to protest against proposed alliances with non-Evangelicals, only to discover that such alliances were already implicit within their own denominational structures.

Evangelical Anglicans had followed J.C. Ryle in arguing that the Church of England was a Reformed Church in which liberals and Anglo-Catholics were interlopers. But many of the younger Evangelical Anglicans, in the fifties and early sixties, began to feel that their traditional position was untenable.

They were unwilling to resolve their inconsistencies along the lines suggested by Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones at the Evangelical Alliance meeting in October 1966. Greater co-operation with other Evangelicals outside the Church of England did not attract them. Instead, they chose the path of Anglican comprehensiveness, and came to accept the position that the Evangelical voice was just one of a number of equally valid contributions within the Church of England.

Growing into union?

The first National Evangelical Anglican Congress, meeting at Keele in April 1967 under the leadership of John Stott, disowned their former position. Thereafter, Evangelical Anglicans sought to influence the Church of England through wholehearted involvement with liberals and Anglo-Catholics in every department of the church.

In dealing with the New Anglican Evangelicalism versus the Old (Ch. 4), Mr Murray traces the changing attitudes of Dr Packer. He moved from a position where he could only envisage unity on the basis of fundamental truths alone (the 39 Articles; pp 82-87) to one where he collaborated with Anglo-Catholics in the publication of Growing into Union (1970).

The Evangelical and Anglo-Catholic contributors claimed complete accord on such issues as Scripture and tradition, justification by faith, the nature of the church, and the sacraments. This book, more than anything else, served to alienate independent Evangelicals, anxious to maintain gospel truth, from Evangelical Anglicans.

Iain Murray presents evidence, both for the changing nature of Evangelical Anglican leadership from the mid-1960s (pp. 138-144), and for the doctrinal downgrading which was also taking place (pp. 145f).

Nothing to say

Unity and co-operation were beginning to be seen as more important than the nature of gospel truth. Billy Graham had begun to co-operate actively with liberals and Roman Catholics in his Crusades.

Evangelicals, both in the UK and the USA, were seeking recognition, influence and intellectual respectability through their scholarly contributions. But they secured their aims only by abandoning a truly biblical position. Though Evangelicals have succeeded in securing the ear of US presidents, obtained bishoprics, and have sat at top tables in liberal theological faculties, the compromise involved has often left them with nothing to say.

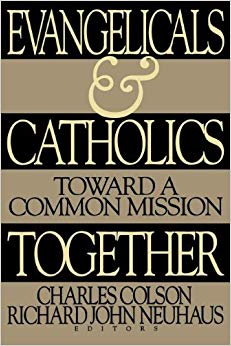

The publication in the USA of Evangelicals and Catholics Together (1994) provided further evidence of the degree of compromise which had afflicted Evangelicalism. Dr Packer and other Evangelicals, together with Roman Catholic leaders, jointly endorsed this programme of collaboration.

Mr Murray deals with the effects of this publication at length (pp. 221-244). Attempting to seek maximum unity and co-operation with Roman Catholics, the collaborating Evangelicals have succeeded only in creating further division among Evangelicals! Though the contributors referred to their ‘Christian’ standing, and speak of the advancement of ‘the gospel’, nowhere was any attempt made to define these terms — a very necessary exercise.

Truth of the gospel

Strange as it may seem, two men who saw the issues regarding Christian unity with clarity were at theological extremes. One was Michael Ramsey, the Anglo-Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury (1961-1974), who sought unity with Rome; and the other was Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, minister of Westminster Chapel.

Both men sought genuine unity between Christians and not a ‘sham unity’ (Ramsey, p.84). What they both appreciated was that the only basis for such unity must be the irreducible minimum which makes a man a Christian. For Ramsey, it was baptism administered by the church; for Lloyd-Jones it was an acceptance and belief of the truth of the gospel.

There can be no reconciliation between these two positions, and Evangelicals have been mistaken in thinking that there can. Mr Murray quotes David Wells with approval: ‘the most urgent need in the church today, even that part of it which is Evangelical, is the recovery of the gospel as the Bible reveals it to us’ (p.310).

Someone has said that if we are ignorant of what happened before we were born, we are condemned to live our lives like children. That is true, and for that reason this book will increase in importance as the years go by.

I would urge, in particular, all ministers and church leaders to read it. But Iain Murray has such an engaging style of writing that any believer wanting an insight into the present condition of Evangelicalism would be well advised to purchase a copy.

Evangelicalism divided is published by Banner of Truth Trust, 342 pages, £13.50 ISBN 0-85151-783-8