In 1919 China, a belated ally of Britain in the First World War, was present when the treaty of Versailles was drawn up. The treaty, however, failed to meet China’s demands: the country had not succeeded in ridding itself of foreign presence on its soil. German concessions in China were not revoked but merely transferred to the already encroaching Japanese.

Briefly, the divided nation of China was united in its outrage. Efforts at republicanism so far had not succeeded. But now, fully roused, the Chinese together began to look for a solution to their problems. Every type of ideology was eagerly considered by Wang Ming Dao’s contemporaries.

It was then that Russia made its first overtures to China. It saw that the establishment of communism in that vast country would be a grand advertisement for its own world-embracing ambitions. So Russia proffered its political scheme to China, ‘the sick man of Asia’, as the panacea the people sought.

Baptism

Meanwhile, Wang Ming Dao knew he was being watched. At the boarding school he had diligently endeavoured to observe God’s Word and was held in high esteem by the principal and students. But his fellow teachers watched him in envy.

Wang Ming Dao’s job was on the line. He had discovered believers’ baptism by immersion in the Scriptures. For Wang to become a Baptist, however, could not be countenanced by the Presbyterian school. What would Wang do? As China continued to struggle with poverty, a job like Ming Dao’s could not be lightly surrendered. His reputation and prospects would both suffer. The cost was high. Determined to be baptised as a believer, Wang was dismissed from his post.

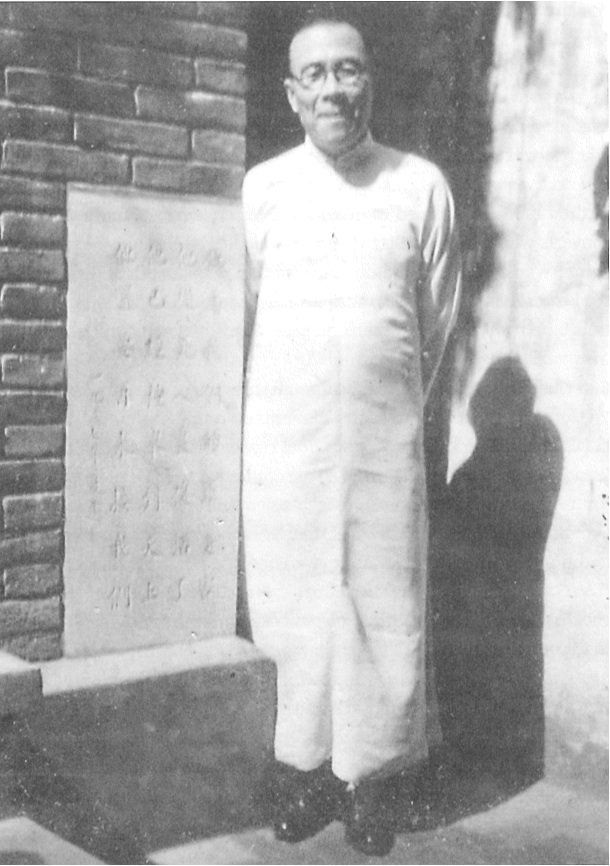

In January 1921, Wang Ming Dao made his way to where a frozen river gave way to an eddy at the foot of a little sluice. There he was baptised, making a public declaration of his faith in the Lord Jesus Christ – the One who alone could bring lasting hope to a troubled people. ‘Lord’, Wang prayed as he stepped into the water, ‘I am doing this because I want to obey you’. Then he returned to Peking to live in the poor home of his mother and sister.

A new weapon

On Wang’s return to Peking, Wang’s mother and sister heard his story in angry astonishment. If not misguided, then he must be mad. In old age, Chinese mothers still looked to their sons for their very survival. Now perpetual poverty faced them. Neighbours and friends were equally loud in their condemnation. To be surrounded by hostility, said Wang, ‘I found to be indeed an unpleasant experience’.

Wang Ming Dao’s faith was shaken. Why had God not vindicated him? But through this bitter experience, God was to furnish him with a weapon, which he would wield in the fiercer battles that lay ahead. That weapon was the sword of the Spirit, the Word of God.

Firstly, 1 Corinthians 10:13 came powerfully to his mind – God would not allow his temptation to be more than he could bear. Then Wang considered how the Lord himself had met and overcome temptation by the Word. So Wang retired into the inner court of the home. There he began an intensive study of the Scriptures.

He busied himself too with home chores, thus giving careful attention to adorning the doctrine of God his Saviour. Wang’s able mind was memorising long portions of the Scriptures. His roots were going down into them and, finding Christ there, he drank deeply of the water of life. Hidden meanings in the Word of God now began to be revealed to Wang. ‘Some of God’s promises’, quoted Wang, ‘are written in invisible ink. Only in the flames of suffering do they become manifest’. The one who was to become the Iron Man of China was strengthened.

Justified by faith

But Wang Ming Dao still had one more essential lesson to learn.

He had maintained links with the Pentecostal Church since his baptism, but saw that the possession of the so-called spiritual gifts did not always go hand in hand with a godly life. Nevertheless, deeply convinced of the necessity of holiness in the Christian’s life, he believed the teaching that complete sanctification was essential for eventual salvation. But though he toiled under the threat of a broken law, Wang Ming Dao recoiled from the pastor’s exhortation that the congregation should display (and read daily) a list of eighty-three sins to be avoided.

Instead of complying, Wang turned to another Pentecostal, a Swedish missionary, Eric Pilquist. The elderly man led the youthful Wang gently through many Scriptures to open up to him the doctrine of justification by faith. Ming Dao experienced the peace of true gospel understanding.

This inestimable service scarcely completed, Eric Pilquist died. ‘Now’, says Wang, ‘there was a great change in my beliefs’. He severed his links with the Pentecostal Church. ‘It was well’, he says’, ‘that God had not earlier opened a door of ministry, for in that case I should have preached a distorted version of the truth’.

Wang Ming Dao’s message to the nominal Christian Church that, ‘only by the works of faith could one justify calling himself a Christian’, was now laid on the firm foundation of justification by faith. Wang Ming Dao was ready to begin his life’s work.

Unconverted ministers

In 1924 Wang Ming Dao began to share his new-found joy with one or two, gathering around the Word of God. Soon others joined them. They were attracted by Ming Dao’s love for his God and Saviour, his sincerity, and his integrity. An influential lady in Peking perceived his deep knowledge of the Scriptures and recognised his gift. She invited him to speak at a united ladies meeting. Wang Ming Dao became known, and the path of service opened up before him.

The Boxer uprising in 1900 (which had ushered baby Wang Ming Dao into the world) had resulted in China paying a large amount of indemnity money to America for losses in the rebellion. Twenty years on, the recipient of that money had spent a considerable part of it in financing the education of Chinese students in America.

These students invariably returned to China to teach. A large proportion of China’s schools were mission schools, the student teachers, having been influenced by Christianity in America, swelled the ranks of the church in China.

However, the returning students brought with them the ‘progressive’ ideas current in the West. The destructive influence of this modernism, together with the churches’ many unconverted ministers and spiritual poverty, weighed heavily on Wang. He realised that ‘the pillar and ground of the truth’ was being threatened (1 Timothy 3:15).

Speaking boldly

As the young preacher moved among the churches, he spoke out boldly. ‘Many preachers’, he taught, ‘proclaim a message … from which the atoning work of Christ is absent … Without the work of atonement there can be no salvation, no forgiveness of sin and no eternal life … May all of us who have been redeemed by the precious blood of Christ … strive in every way possible to spread this gospel’.

Of course, this teaching aroused opposition. Ming Dao knew what it was to be denounced and cursed. But though he was wounded, and sensitive to disapproval, his previous suffering had prepared him. ‘God did not allow his feet to be moved’. Wang testified that God had brought him ‘through fire and water’, but, he continued, ‘he brought me into a wealthy place’ (Psalm 66).

Wang longed to see spiritual purity in the church, and taught conformity to the character and attitudes of the Lord Jesus Christ. And those who desired spiritual growth and encouragement in their pilgrim walk loved his ministry. He began to be invited to preach far and wide across China.

Marriage

It was on one of these preaching tours that Wang Ming Dao met Lui Jing Wun. Wang knew that his mother, Wun-I, wanted him to marry. But, she said, it must be someone from Peking – someone she knew. It was not to be someone from south of the great river. The dark Southerners, she declared, were barbarians.

It was in 1925 that Wang travelled south and stayed in the home of Pastor Lui Den Shun. He experienced the loving warmth of a Christian home, something he himself had never known. Wang was captivated by the maturity of Den Shun’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Jing Wun, as she played the organ in church. He asked for her hand in marriage.

Amazingly, Wun-I made no objections to the marriage, and in 1928 Wang brought his young bride to live in his family’s home. Did Jing Wun’s mother have some notion of what awaited her daughter, as she questioned Wang? If suffering was, as he had taught, an essential part of a Christian’s life, how would Jing Wun, who had never known it, cope?

Brought by God

Wang himself was naïve. He knew nothing of the lot of Chinese daughters-in-law. They were just outsiders, little more than slaves in the family home where they must live. On the bride and bridegroom’s arrival, the house was cold and empty – there was no smile or meal to welcome them. Mothers-in-law felt revenged for their own past treatment as they propagated a cruel old Chinese custom.

But Jing Wun encouraged Wang. ‘I have been brought by God into this situation’, she constantly told him. Wang was yet to discover just how resourceful, generous and godly she was. How thankful he would one day be for her sound judgement and loving concern. Sometimes Jing Wun’s carefree ways exasperated her meticulous husband. But even her faults and failings, he would acknowledge, helped him to become more like his Master.

One day Jing hurried off to a meeting. ‘Have I got time to drop these shoes in at the boot repairers?’ she wondered. She dumped the paper-bag on the shop counter and turned to leave. ‘What sort of repair do you need?’ the boot mender asked. As she rushed out of the shop she called out, ‘Just have a look and mend them where they’re worn’. The bag contained three pig’s trotters!

Ease up?

Since 1925 Wang Ming Dao had been receiving requests for written notes of his sermons. So it was that, in 1927, the Spiritual Food Quarterly came into being. No longer was the often ambiguous, classical style the norm for written texts in China. The easier vernacular style had been introduced in 1920, and this no doubt greatly increased the readership of Wang’s periodical, as it circulated throughout China in the dark days ahead.

By 1930 Wang Ming Dao had preached to hundreds of thousands. Many however continued to call him proud, judgemental and unforgiving. On one of his journeys, as the train trundled across China, it seemed to hammer out the admonition: ‘Ease up a bit, stop censuring apostasy’. But then Wang recognised the familiar voice of the tempter, as he whispered, ‘You could be more widely used, so much more influential’. So, in the steps of his Master, Wang set his face like a flint, and pursued his God-given task.

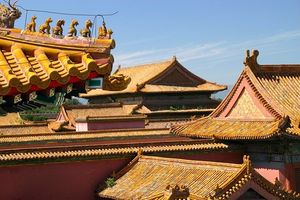

God blessed Wang Ming Dao, and the church in Peking grew. Baptisms were conducted and an annual conference started. Many crowded to hear the preaching, often having to stand in the cold and wet around the rented premises Wang used. So it was that, in 1937, the Christian Tabernacle was built.

But one week before it was due to be opened, the Japanese attacked the Chinese at the Marco Polo Bridge outside Peking, a battle that was to merge into the Second World War. One month later the Japanese marched into Peking.