1. The neglected years 1662-1737

It is fifty years since the first Puritan Conference was held at Westminster Chapel. Since that time Christians throughout the world have had the benefit of many Puritan reprints. We have been able to enter into the great inheritance left by the Puritans.

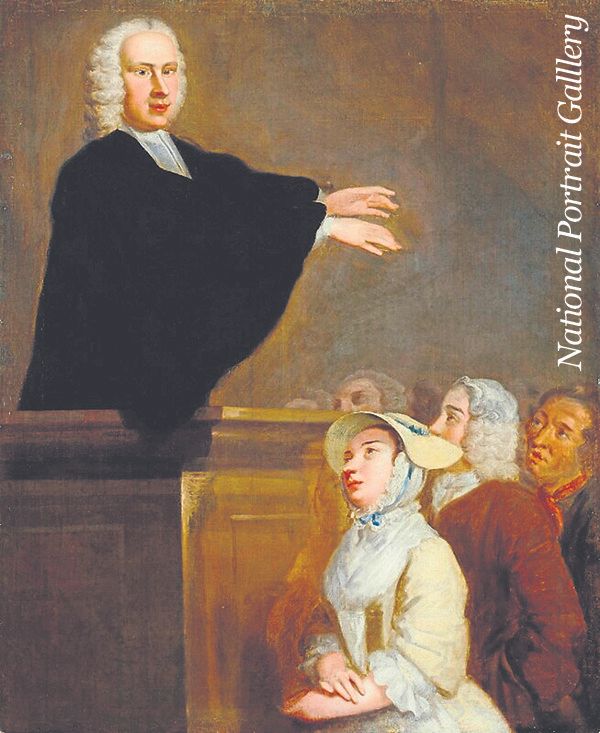

Special attention has also been paid to the ‘Great Awakening’ of the early eighteenth century, in which Whitefield and Wesley were prominent. But what about the intervening years? What do we know about the period between the ‘Great Ejection’ of 1662 and the ‘Great Awakening’ of the 1730s and onwards?

We have heard of Watts, Bunyan and Doddridge. We may also know about the 1689 Baptist Confession. But what else do we know? Was nothing happening worthy of attention?

We have been told that this was a barren period. Bishop J. C. Ryle is most emphatic that this was a period when ‘natural theology, without a single distinctive doctrine of Christianity, cold morality or barren orthodoxy formed the staple teaching both in church and chapel. The Nonconformist body … existed … but could hardly be said to have lived. They did nothing, they were sound asleep’.

According to Ryle, when the great change came, it ‘came from the Church of England as a body. Nor yet … from the Dissenters. The men who wrought deliverance for us were a few individuals, most of them clergymen of the Church of England’.

Spiritual life

This negative view is shared to some extent by some Baptist historians. Others, however, offer a different picture.

In his Congregational History Waddington writes: ‘It is rather unusual for Nonconformist historians to notice the humble and almost nameless people who met in “dark conventicles”. They felt a natural pride in tracing their origin to Cromwell, Owen and Baxter. None of our word-painters have attempted to sketch these village churches in the day of small things’.

Historians David Bogue and James Bennett, in their History of the Dissenters 1688-1838, supply what is lacking. They complain that church history has concentrated on the wrong things.

‘The exterior of the church is presented to us with sufficient fullness, but the interior is not disclosed to view’. They continue: ‘The advancement of spiritual religion in the soul, the conversion of sinners, and the edifying lives of the disciples, in the exercise of the gifts and graces of the Holy Spirit, are topics for which the reader looks almost in vain’.

These historians set an example in the way they have looked for spiritual life in their study of church history.

Spiritual prosperity

Christians had little interest in the Anabaptists of the Reformation period until Leonard Verduin wrote The Reformers and their stepchildren. Since that time other books have followed, and Christians have at last been given the other side of the story.

Some Anabaptists were indeed guilty of fanaticism, and others of serious error, but much more needs to be said. Our view of these people has been biased by a one-sided and neglectful presentation of their history.

The purpose of these articles is not to deny the weaknesses of Nonconformists during this period, but to identify what they were and to expose another side of life among the Dissenters, one that sets a shining example of church life that we do well to emulate.

Bogue and Bennett describe the Dissenters as a whole over the period 1688-1714: ‘Few in any age were better instructed in the doctrines and duties of Christianity and could give a more reasonable account of the hope that was in them.

‘While they were content to suffer for their profession, always to be despised on account of their singularities, and frequently to endure other serious injuries, it is fair to say that the state of religion among them was prosperous’.

The test of persecution

The historians go on to describe the Nonconformists’ view of the character of God, the state of man, the character and office of Christ, the way of receiving salvation through Christ, and practical godliness.

They assert: ‘In the whole history of the Christian church it would perhaps be difficult to find so great a number of ministers in one religious community by whom principles usually denominated evangelical were generally preached as the Nonconformists, whose faith stood the test of persecution.

‘Those who entered into their labours brought forward the same doctrine, which they had been accustomed to preach and, indeed, congregations so intelligent and so pious would have borne with nothing else’.

The authors maintain that ‘in the Christian world during this period there was not to be found a body of people who excelled the English Presbyterians, Independents and Baptists in the knowledge of the principles of the gospel, in the uniform and persevering practise of its precepts, and in the diligent and faithful observation of its ordinances’.

Savour of divine things

Isaac Watts makes similar observations in his account of life among Nonconformists of his day. ‘They were very careful to observe family worship and sanctified the Lord’s Day. They were careful to maintain private prayer and reading of Scripture.

‘Morning and evening they had their season of retirement and according to their task or leisure or piety, half-an-hour, an hour or more, was employed in reading the Scripture, in perusing the more spiritual writings, chiefly of the Puritans and Nonconformists, in meditation, in self-examination and in prayer.

‘From this employment they came forth into the bosom of their family and to the duties of their station in society with a sweet savour of divine things upon their heart and a reverence of God’.

It is also known that they avoided all taint of worldliness, were diligent in business, and frugal and economical in their affairs. Consequently, bankruptcy was almost unknown among them. They were also careful to exercise Christian benevolence.

Going astray

The account clearly contradicts the accepted view, and some explanation is needed. Bogue and Bennett recognise that after the reign of Anne, in the early eighteenth century, the General Baptists were starting to go astray, as were individuals among the Presbyterians. But they did so in a secret manner by keeping back the truth rather than by positively extolling error.

However, Unitarianism crept into West Country Presbyteries and in 1719 a gathering of ministers was called at Salters Hall in London in an attempt to halt the spread of heresy. This gathering did little except expose the presence of the same heresy in Presbyterianism and their unwillingness to deal with it.

Within a relatively short time the Presbyterian denomination started to decline, and Presbyterian ministers became alarmed. The English Presbyterians thought that other denominations were in the same mess as themselves, but this was not the case and it is important to make this clear.

‘Sensible advances’

Three leading Presbyterian ministers bemoaned the fact that their Church was in serious decay and, in March 1730, Watts gave his opinion as to the general situation, writing: ‘So far as I have searched into the matter, I have been informed that whatsoever decrease may have appeared in some places, there have been sensible advances in others’.

The following year, an unknown Christian from East Anglia visited London to examine the condition of churches and give an account of what was going on. His purpose was to ‘stop the prevailing humour of some people which they were officiously spreading that this Dissenting interest is in a very low and declining condition’.

He produced what is known as The London Manuscript. This was obtained by a certain Samuel Palmer who deposited it in the Dr Williams Library in London. This fascinating document exposes decay among the Presbyterians but prosperity among the Independents! The General Baptists also declined, but not the Particular Baptists. A careful analysis of the growing number of Particular Baptist meeting places proves this to be the case.

Bogue and Bennett detail the desolation among Presbyterians but assert that ‘there was a great multitude of flourishing congregations in most parts of the country which were increasing with a steady progress’.

Likeness to Christ

When we consider church history we must remember that we are looking at the history of ‘the body of Christ’. If we want to identify the true church and distinguish it from the false, this is the perspective we should adopt.

The true church, like her Master, will be ‘despised and rejected of men’, but will be full of ‘grace and truth’. Outwardly, there may be not much to show, but inwardly there will be the fruit of the Spirit.

There will be true holiness and love. The congregation will be the dwelling place of Jesus Christ. His power will be exhibited in the conversion of sinners and in the unity of the local body in the bond of peace. The heavenly harmony of the people of God will reflect the unity in the Godhead.

Life in the local church

When Christ, whose eyes are as a flame of fire, looked at the seven churches of Asia Minor in Revelation 2-3, he saw through the pretence of Sardis and Laodicea, but treasured the faithfulness of Philadelphia.

The New Testament has much to say about the spiritual condition of local congregations and little by way of statistics and names of prominent men. It is the life of local churches that matter to the Head.

Christ is looking for a reflection of his own image, and working to that end. He is preparing his Bride for himself. ‘The King will greatly desire her beauty’ (Psalm 45). As we look at the ‘neglected years’ we shall endeavour to see a spiritual heritage that many have missed.