For lovers of God’s Word and ways, there are names littered throughout church history which stir feelings of profound gratitude. These names are centuries old, many of them dating from the Reformation.

They are the names of men and women to whom we owe an enormous debt. In many cases they laid down their lives so that we could have the Word of God and the amazing Christian heritage which we now enjoy. They are the great heroes of church history, men and women whom we eagerly look forward to meeting some day in heaven.

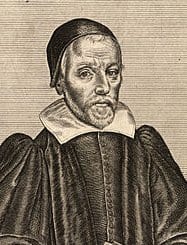

But there are others whose names have sunk into obscurity, who are little remembered, but whose legacy is of equal value. One such was Giovanni Diodati, who died 350 years ago this month.

Consummate scholar

He was born at Geneva on 3 June 1576 and raised in a family that had once had close links with the papacy and the enemies of reform. (His father had been christened by Pope Paul III, with Charles V as godfather). After being won over to the teachings of the Reformation, his parents had moved from Italy to Geneva to escape persecution.

Giovanni was educated at the University of Geneva, and was such a diligent and talented scholar that he gained a Doctorate in Theology at the age of eighteen. History records that he was merry and playful with his students, yet erudite among men of learning.

In his early twenties he became Professor of Theology at the University of Geneva, a post held by Calvin a generation earlier. Yet he declined to be ordained until he was thirty-two, believing that academic studies were not sufficient qualification for this office, and that he must first gain more experience of life.

Diodati was a consummate scholar of Hebrew and Greek, and was thoroughly conversant with the Scriptures. It is not hard to see how the truths of God’s Word would have penetrated his heart, and at a young age he was a passionate lover of the Bible. On 10 December 1600 he married Maddalena Burlamacchi, and in due course four girls and five boys were born to them.

The Bible in Italian

In 1603 he began a translation of the Bible into Italian, and this was published in 1607. It was not the first Italian translation of the Bible, but was acknowledged to be the best. He issued an edition of the New Testament in octavo form, specifically for circulation in Venice.

As soon as it appeared, his Italian Bible was highly acclaimed by some of the greatest minds of his time. It had its critics, too, who regarded it as more a paraphrase than a translation. Nevertheless, even they conceded that Diodati was the most faithful translator to date.

The collective opinion of Diodati’s contemporaries was that his translation was distinguished by its fidelity to the texts, the clarity of its rendition into Italian, and the literary merits of its style. In the course of a journey to Italy in 1638-39, John Milton made a stopover in Geneva, and for about a month the great English poet had frequent conversations with Diodati.

In 1641 Diodati published a third edition of his Bible, with accompanying notes. He was regarded as one of the seventeenth-century’s greatest Bible commentators and exponents of evangelical doctrine. The burden of Giovanni Diodati’s heart was for his own country, Switzerland, where the nascent Reformation had been nurtured, and for Italy, still in the grip of Rome and a fierce enemy of evangelical truth.

Not without hope

The Republic of Venice was the most liberal in Italy, and in that area there were increasing numbers opposed to the pope. It was through these people that Diodati sought to disseminate the Word of God and effect the spiritual liberation of the province. His own words were: ‘I am not without hopes of effecting the entrance and diffusion of copies into Venice, where superstition has already sustained a breach, through which liberty has entered, which God will sanctify with His truth when the time is come’.

Diodati also published, in 1644, a translation of the Bible into French. This version is acknowledged to be inferior to his Italian one. He was not at ease in the French language as he was in Italian, and did not achieve the same clarity and elegance of language. Nonetheless, after a long delay, his French translation was finally approved by the Body of Pastors of Geneva.

In 1605, while his Italian translation of the Bible was still in progress, Diodati set about preparing the ground with visits to Venice to teach and encourage the believers there. He met with opposition from the pope, who had placed spies to intercept his Bibles. The Roman Church was aware of the harm it would suffer from the Bible being freely available to the people.

In the province of Venetia he found that sympathy to his cause stemmed more from hostility to the pope than from faith in the gospel, Pope Pius V having excommunicated the Republic in the 1560s. Diodati returned to Geneva aware that there was still much work to be done.

Reformation arrested

Fra Paolo Sarpi was an accomplished scientist, doctor of theology, and Diodati’s best ally in trying to bring the gospel to the Venetian people. In 1605 he recorded that among the common people in Venice there were twelve to fifteen hundred who were minded to renounce the Roman Church. However, although many of the nobles embraced evangelical doctrine in their hearts, they preferred not to disclose their allegiance as long as they risked danger to themselves or the Republic by doing so.

Sir Henry Wotton, the English ambassador to the Venetian Republic, championed Diodati’s efforts. In 1607 he invited him to return to Venice, assuring him of a warm welcome from Fra Sarpi, but advising him to travel under an assumed name for his own safety.

In 1608, travelling under the name of Coreglia, Diodati took up the invitation. The Reformation in Italy was, however, arrested by a chain of political events. Letters were intercepted by the Jesuits, Henry IV of France was assassinated, and Sir Henry Wotton was recalled to London.

Unanimous choice

Diodati’s hopes for the advancement of the Kingdom of God in Italy were dashed, and he turned his attention elsewhere. The enemies of reform began to rise up, and Geneva found itself under threat. Diodati made a fruitful trip to the Reformed churches of France to seek money and arms for the defence of Geneva.

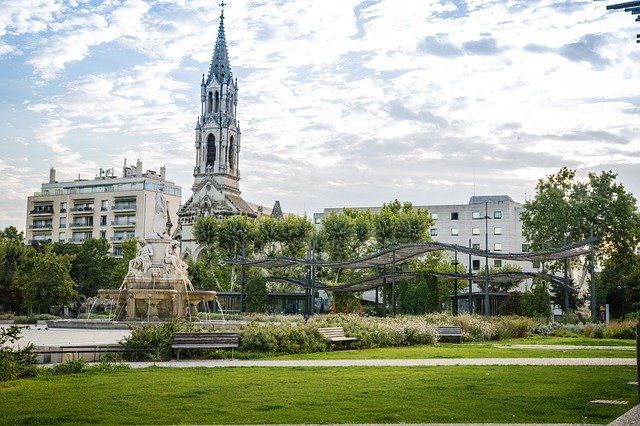

As a result, relations between these churches and the Genevese Protestants were cemented. Some of the French churches invited Diodati to be their pastor and he spent some months preaching and teaching at Nîmes, then at Pont-de-Veyle.

In 1618 a dispute arose, partly theological and partly political, between the Calvinists and Arminians in Holland. This culminated in the Synod of Dordt, which took place from 13 November 1618 until 9 May 1619. Diodati was among those sent to represent Geneva at this assembly. The Genevese delegates impressed the Synod by the skill and wisdom with which they condemned the doctrines of Arminius and maintained Calvinist teachings.

Diodati was the unanimous choice to compile the ‘Acts’ setting out the conclusions of the assembly. These conclusions were that the doctrine of Arminius was contrary to the Word of God because it put the onus for salvation on man and not on the grace of God.

Italy’s Tyndale

In 1691, against its author’s wishes, Fra Paolo Sarpi’s history of the Council of Trent was published in London in the Italian language. Diodati translated this into French. No doubt, he relished the opportunity to make available to his French readers a work which sought to expose intrigue and scandal within the Church of Rome.

Other writings by Diodati include a translation into Italian and French of a work by Edwyn Sandys, an English MP, entitled A report on the state of religion in the west. He also rendered the Psalms into Italian verse.

He wrote several pieces in Latin setting out the biblical teaching on topics of interest and concern. These include Of Purgatory, an invention of priests, Of the Word of God, Christ the Mediator, and Of the Lord’s Supper. In addition, a large number of his sermons and discourses were published. Only once was he censured by the Protestant church in Geneva — for speaking out against the execution of Charles I of England. He undertook not to speak of it again, but to pray for the peace and prosperity of England.

In 1644, illness forced him to relinquish his chair at the university, and for the next five years his health declined owing to liver failure. He passed into the presence of his Lord on 13 October 1649, having said goodbye to his family, and with the words of Simeon on his lips: ‘Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace’.

Diodati is to ‘La Bibbia’ in Italy what William Tyndale is to our English translations. He is one of those of whom it may be said, ‘he being dead yet speaketh’.