Christians, of all people, should be interested in history. The Bible, after all, is to a marked degree the history book par excellence. It is the record of God’s mighty actions in creation and redemption. The twenty centuries that have followed since its completion have been the ongoing record of God’s dealing with his people, as the church militant moves towards the final victory.

History is linked with particular individuals and hence with the location where they were born and where they grew up. The tourist trade has grasped the fact that people will want to visit those locations which enhance their memories of great figures of the past. Heritage centres have become a very popular feature, where we can revisit the world in which our ancestors grew up.

For Christians, a location will recall some great movement of the Spirit of God. We reject the notion of merit-claiming pilgrimages. All we want is to know God better and one way of doing this is to recall the past. It is not that we want to elevate history above Scripture. The Bible reigns supreme! Christian history is simply the illustration of the grandeur of God’s great purposes.

Insignificant places

I am impressed by the way God works often in obscure localities. Twentieth-century evangelicalism talks about strategy and tactics, about key groups to be reached and new methods to be adopted. If we go back to the eighteenth-century evangelical revival, it is noticeable that God worked in apparently insignificant places – John Newton’s Olney; John Berridge’s Everton (Bedfordshire!); Henry Venn’s Yelling; and Daniel Rowland’s Llangeitho.

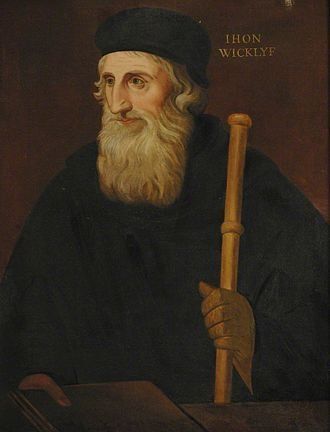

One stimulus to my memory has recurred every time I have driven south on the M1 from junction 21. It is the rather insignificant sign on the embankment indicating the ‘River Swift’, close to Lutterworth. To millions who have sped past it, it has probably been no more than one of many motorway signs. To the Christian who has read of the dawn of the Reformation, however, it recalls the man who has been dubbed ‘the Morning Star’ of that Reformation, the harbinger of a new day. It recalls John Wycliffe who died in 1384 at Lutterworth.

In 1428, over forty years after Wycliffe’s death, the pope, in a fit of petulant rage, ordered his bones to be dug up and burnt to ashes. The ashes were scattered on the River Swift. It was an indication of how Rome saw Wycliffe as a powerful enemy. The futile edict of the pope earned the scornful rejection of his action reflected in a popular saying: ‘The Swift carried them to the Avon and the Avon to the Severn and the Severn to the oceans of the world. So Wycliffe’s teaching could not be hid.’

Turbulent times

It had been a turbulent century. The ‘Black Death’ had hit England in the late 1340s. Something in the order of one third of the population of Europe died in the ravages of bubonic plague carried by infected rats. On the economic front, the depleted labour force was in great demand and this led to a refusal by the peasants to be exploited. The final explosion of their protest was seen in the peasants’ revolt of 1381, sparked off by the imposition of a poll tax. Only once since then has a British government imposed a poll tax, and that led to riots in Trafalgar Square and the fall of a prime minister!

Wycliffe was a Yorkshireman, from Wycliff near Richmond. He lived in a period when surnames were being developed, and often it was a place of birth or an occupation which provided the surname. He lived also at a time of transition for the English language, which meant that a further translation of the Bible by Tyndale would be needed in less than two centuries. The invention of printing, and the setting up of Caxton’s printing press, were nearly a century ahead. Luther’s historic stand lay almost a century and a half in the future.

All these factors indicate how much he was a pioneer. The title ‘Morning Star’ was appropriate, since the morning star heralds the end of darkness and the dawn of a new day. The darkness of gross superstition had hung over the churches. The arrogance of the priest and pope brooked no opposition. The corruption of the papacy knew no bounds. Then God raised up Wycliffe!

The Bible for all

He went as a student to Oxford and ultimately became Master of Baliol College where his influence was felt by generations of students. He spent his closing years as Rector of Lutterworth. He was slowly moving to an understanding of the truth, though the fuller clarity of Luther and Calvin was still to come. Yet Luther himself acknowledged his debt when he confessed that he had ‘become a Wycliffite’!

Wycliffe’s preaching and writing aimed at recalling Christians to the supremacy of Scripture. A ritual must not be accepted because it was well established, but must be tested by biblical teaching. Such dogmas as transubstantiation, with the alleged miraculous change of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, were rejected.

Early in the century, in 1302, Pope Boniface VIII had claimed that outside the Roman Catholic Church there was no salvation. Wycliffe rejected this, and attacked the whole Roman system, especially its notion of a priestly caste. In its place he urged the need for a preaching ministry. This led him to train men in Oxford to take the truth to the towns and villages of England.

Linked to this emphasis on the Bible and on preaching was his concern to see the Bible translated into the common tongue, so that Christians might be strengthened, churches built up and sinners saved. To return to the River Swift – the stream of truth would flow to the farthest ocean. To recall the title of the ‘Morning Star’ – the full blazing dawn of the Reformation was at hand.