Havelock’s first four years after returning to India in 1851 were unremarkable until, unexpectedly, he was appointed Adjutant General of the British Army in India. He was now responsible for the efficiency of all regiments in India and their readiness for war.

In 1855 war looked somewhat remote but, since the Afghan disasters, Indian belief in Western supremacy had waned. Indian recruits (Sepoys) outnumbered British troops by five to one. 1857 was the centenary of the Battle of Plessey, and Havelock knew that it would take only a spark to set Bengal ablaze.

His entire energies were devoted to improving efficiency, fighting complacency and overcoming the prejudice of those who resented his insistence on an intense application to duty. He had to shake commanding officers out of satisfaction with second rate discipline, because he knew their very lives depended on it.

Mutiny

In May 1857 Havelock returned from a brief campaign in Persia to hear that native regiments in Meerut had mutinied and that the fortress of Delhi was in the hands of the mutineers.

The mutiny was touched off by the belief that the cartridges of the powerful new breech-loading Enfield rifle were greased with animal fat, and that Hindu and Muslims would thus be defiled when biting off the ends before loading.

This spark, fuelled by misjudgement and folly on the part of local commanders, ignited dissatisfaction in the Bengal Army. Havelock sailed for Calcutta, taking his difficult son Harry with him as his personal staff officer.

Five days later they were shipwrecked off Sri Lanka. In miraculous circumstances, not dissimilar to St Paul’s experience off Malta, all passengers and crew survived, and Havelock led a thanksgiving service afterwards.

As Havelock travelled he wrote a memorandum recommending stringent measures: ‘It is clear that no regular native infantry regiment can now be trusted. All are in heart implicated … if not in fact … no piece of cannon must henceforth be entrusted to a native … the whole of the Enfield rifles must be given to British troops’.

Appalling task

The acting Commander-in-Chief, Sir Patrick Grant, supported most of Havelock’s proposals. He recalled Lord Hardinge’s words: ‘If ever India should be in danger, the Government has only to place Havelock at the head of an Army, and it will be saved’. On 17 June, Lord Canning met Grant as he disembarked, who led Havelock forward and remarked: ‘My Lord, I have brought you the man’.

Havelock was appointed to command a mobile column with the task of relieving Cawnpore and then securing Lucknow, where his friend, the Resident Henry Lawrence, was under pressure. On Havelock, therefore, depended the restoration of British authority in the lower provinces. The outcome would affect India for years to come.

Havelock himself was now sixty-two and the climate was intense. Time was against him and he would have to march his men beyond the dawn hours. Canning and Grant had refused to disarm every Sepoy in lower Bengal, his troop strengths were barely sufficient, and he would be operating in enemy territory.

Cawnpore

Lawrence wrote to Havelock describing his situation, adding that the column should be able to overcome opposition in Cawnpore ‘provided Wheeler holds his ground; but if he is destroyed your game will be difficult … Your detachment should not lose an hour. This is important on your own account and of vital importance on Wheeler’s. We are threatened by about ten regiments … On your approach to Cawnpore, I will endeavour to co-operate with you; but as long as so strong a force is close by, it will be impossible’.

Three days later Havelock was woken to be told that Cawnpore had fallen and all the Europeans murdered.

On 7 July, Havelock’s force set off from Allahabad. It was not large — 1000 Europeans and 200 Sepoys. It included the Seaforth Highlanders, who knew Havelock well. Most of them carried a Bible in their knapsacks.

Between 7-16 July this force marched 126 miles, won four battles and recovered Cawnpore. All of this was achieved under the intense July sun and severe monsoon rainstorms. At Cawnpore, by inspiring leadership and courage, young Harry Havelock rallied a wavering battalion and then captured a field gun single-handed. For this epic achievement, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

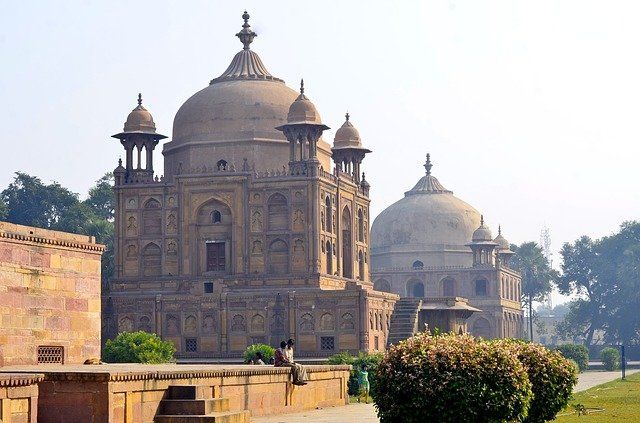

Lucknow

Havelock’s achievements were now spoilt by tragic news from Lucknow; his Christian friend Henry Lawrence had died of wounds. The urgency to press forward to Lucknow, forty-three miles away, was now paramount.

Yet he faced two more blows. Promised reinforcements could not now be spared, and cholera gripped the force. Delay was enforced. Havelock faced the unbearable thoughts that the destruction of Lucknow would be the greatest calamity to the State, and that delay might leave him open to the charge of cowardice.

He wrote home to Hannah: ‘I must now write as one whom you may see no more, for the chances of war are heavy at this crisis… Thank God for my hope in the Saviour, we shall meet in heaven’.

And yet ‘God was with him’. The force pressed on, and Have-lock had a horse shot from under him in action for the sixth time. By 23 September they reached the outskirts of Lucknow in fine weather and facing an enemy of 10,000.

There is not space to describe in detail the epic relief of the Residency on 25 September, with its fascinating points of tactics, command and valour. Havelock rose before dawn that morning at the age of sixty-two, facing the hardest day of his life. As always, he read his Bible and spent time in prayer.

Throughout the previous ten weeks, any mistake or reverse might have been redeemable. On this day, however, a mistake would be fatal — not only for his reputation and his life, but for the garrison who had held out for so long and who were now ‘down to their last biscuit’.

Ammunition was low, and defeat of the relieving force, or even a temporary reverse, would bring disaster. As at Jalalabad, Cawnpore and the battles in between, Havelock commended himself to ‘the same Providence who watched over me’. And ‘God was with him’.

Work of conversion

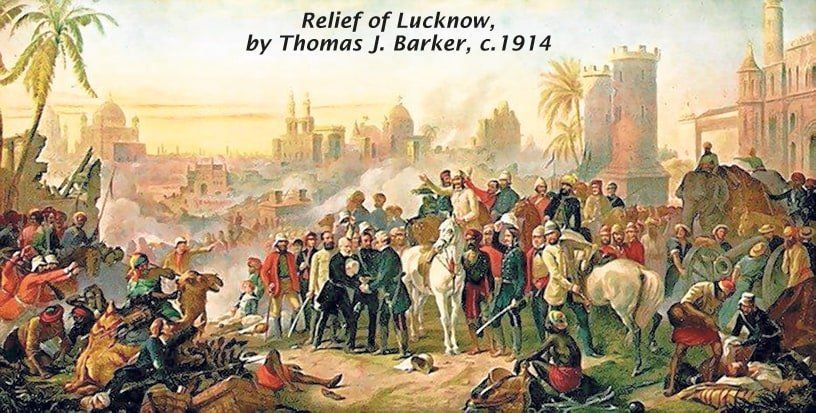

Hours of intense street fighting were rewarded through skilful deployment of guns and the determination of the infantry. The Seaforth Highlanders emerged from an unexpected direction as Havelock lost yet another horse. And this battalion now drove forward, bagpipes skirling, dodging fire, to reach the Residency. Hairy, filthy white men and loyal Sepoys pulled them in. The Residency had been relieved and Lucknow was saved.

‘Rarely has a commander’, wrote the Governor General in announcing the news, ‘been so fortunate as to relieve by his success so many aching hearts, or to reap a rich reward of gratitude as will deservedly be offered to Brigadier General Havelock and his gallant band, wherever their triumph shall be known’.

The relieving force had lost 535 men, killed and wounded. Harry Havelock had also been wounded, and in the days which followed, father and son were drawn to each other as never before.

At last, during these days in the Residency, an event occurred for which Havelock and Hannah had so long prayed — the great work of conversion in Harry’s heart. His resistance to Christ broke down and, as his father had so often urged, he gave his heart and will ‘to the God who governs the earth and the Saviour who died for sinners’.

Trust in Christ

When Harry had first come to India he had regarded his father’s Christian faith as an unnecessary luxury. With all the intolerance of youth, he believed that a good Christian could not be a good soldier. He was ashamed of his father’s taste for prayer meetings and Bible readings.

During the previous three months, however, Havelock had become Harry’s hero. Harry was a good enough soldier to know military brilliance when he saw it. It became the greatest experience of his life to be in close companionship with the foremost soldier of his age.

He also realised how much he had hindered Havelock by his impatience and stormy temper. This humbled him and showed him his need of the inward power which his father so manifestly had.

Supremely he admired his father’s courage, physical and moral, which sprang from his trust in Christ ‘as Counsellor and Friend’. Harry Havelock VC knew he was a sinner and that Christ had died for sinners and lived to forgive and empower them. At last he yielded.

See how a Christian can die

Henry Havelock, now knighted and a major general, had reached the end of his earthly pilgrimage. Three days after contracting dysentery he said to another Christian general, Sir James Outram: ‘For forty years I have endeavoured so to rule my life that when death came I might face it without fear’. The following morning Havelock whispered to his son: ‘Harry, see how a Christian can die!’

An hour or so passed as the son held his father’s head and shoulders in his arms. At half past nine on Monday 24 November 1857, Harry lay back the body. ‘His end was that of a just man made perfect’, he wrote to his mother.

The friendship of Christ was Havelock’s secret and remains his message: ‘It is a happy thing beyond description to have a heavenly Father and a powerful friend in whom to put our trust’.