During the 1830s a great poet emerged in America who was speedily acclaimed as ‘The Cowper of the West’, because of his deeply experimental religious verse. His name was John Greenleaf Whittier and he, like Cowper, had the spread of the gospel at heart. Cowper’s verses praised the work of the Moravians who had planted the Rose of Sharon on Greenland’s icy mountains, and Whittier strove to show how God was working out his purpose in the land of the mogul. One of Henry Martyn’s letters had given him the impetus.

When Martyn arrived in India, he realized what a sacrifice it was to leave all and follow Christ, and wrote home: ‘It is an awful, an arduous thing to root out every affection for earthly things, so as to live only for another world. I am now far, very far, from you all; and as often as I look around and see the Indian scenery, I sigh to think of the distance which separates us.’

These heart-stirring words moved Whittier to write Martyn’s biography in verse. It was read in almost every school in America and placed in almost every public library; it awoke in America an awareness that the earth was being covered with the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.

Born in 1781 at Truro, Cornwall, known for its revival under Samuel Walker’s preaching, Martyn was the son of a miner who had worked himself up in society. His mother died whilst he was but a child.

Martyn studied at Cambridge where his brilliance was rewarded with prizes. He became senior wrangler and was elected fellow of St John’s College whilst only twenty one. Martyn, however, felt he was grasping at shadows. Then his father, a believer, suddenly died, and the shadow-grasper now felt that he had lost his anchor in life. He turned to his neglected Bible and read the Acts of the Apostles which forced him on his knees in prayer to thank God for sending his Son into the world to save him from his sins. Martyn now grew in grace through reading Doddridge’s Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul and sharing sweet fellowship and counsel with Charles Simeon, the Cambridge Evangelical.

God called Martyn to his missionary task through the writings of David Brainerd. He was gripped by young Brainerd’s testimony to the hardships of living amongst the American Indians and times when God hid his face. Martyn saw how, after humbling Brainerd, the Lord suddenly smiled upon him and used him as an instrument of revival. He was also deeply struck by the fact that Brainerd had died, worn out for the gospel’s sake, whilst only thirty-two.

Soon Martyn had laid all ambitions of scholarly fame aside so that he might become a messenger of hope to foreign lands. He was ordained as an Anglican minister and applied to various missionary societies.

Through the agencies of the Clapham Sect and Christian board members of the East India Company, Martyn was offered a post as chaplain to the troops and civil servants in India. As this included freedom to preach to the Sepoys and the native population, Martyn eagerly accepted the offer. He swiftly prepared himself to leave England, weeping tears of joy at being counted worthy to serve the Lord, and tears of grief at leaving his friends. In great sorrow, he said farewell to a young lady whose heart he had hoped against hope would be united to his in marriage. Whittier says:

He went forth

To bind the broken-spirit – to pluck back

The heathen from the wheel of Juggernaut –

To place the spiritual image of a God

Holy and just and true, before the eye

Of the dark-minded Brahmin – and unseal

The holy pages of the Book of Life,

Fraught with sublimer mysteries than all

The sacred tomes of Vedas – to unbind

The widow from her sacrifices – and save

The perishing infant from the worship’d river!

On 21 April 1806 Martyn reached India and his immediate impression was one of horror at the bondage of the people to their idols. William Carey, the Baptist missionary, was overjoyed to meet him and the Serampore trio found such proofs of the young Anglican’s calling and abilities that he was accepted as one of their very own missionaries. Martyn swiftly proved his prowess as a linguist and was soon preaching in Hindustani, drawing 450-800 hearers. He opened schools, providing good, well-paid staff to teach the children. So obvious was the presence of the divine hand on Martyn’s work that the authorities invariably backed him and his fellow missionaries in other denominations gave him their full support.

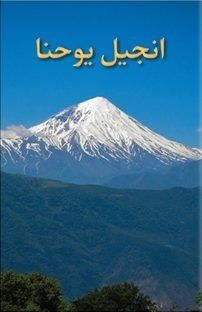

Within two years Martyn had translated the entire New Testament, a Bible commentary and a good part of the Prayer Book into Hindustani, had prepared works in Hindi and had almost completed the Persian New Testament in spite of failing health – he had caught tuberculosis. Instead of returning to England for medical attention, Martyn made the hazardous journey to Persia to complete his translation and witness to the Mohammedans there. His constant prayer was, ‘Oh, have pity on my wretched state and revive thy work, increase my faith. Thou art the resurrection and the life – let me rest on this Scripture.’

Though often threatened with death from without for exalting Christ more than ‘the Prophet’ and wracked with death-bringing fever and pain from within, Martyn entered public debate with the most learned mullahs and mujahidins and the Shah himself received a copy of his Persian New Testament. How times have changed in that country is witnessed by the graceful way in which the Shah accepted the Word of God. Commenting on the ‘high, dignified, learned, and enlightened Society of Christians, united for the purpose of spreading abroad the Holy Books of the religion of Jesus (whom, and upon all prophets, be peace and blessing!)’, His Majesty said how acceptable the book had proved to him and continued:

‘In truth, through the learned and unremitting exertions of Rev. Henry Martyn, it has been translated in a style most befitting sacred books, that is, in an easy and simple diction … We, therefore, have been particularly delighted with this copious and complete translation. If it please the most merciful God, we shall command the Select Servants, who are admitted to our presence, to read to us the above-mentioned book from the beginning to the end, that we may, in the most minute manner, hear and comprehend its contents.’

Fateh Ali Shah Kayar then authorized Martyn’s New Testament to be distributed in Persia with the blessing and full approval of His Majesty.

The enlightenment of this gracious Muslim monarch stands in stark contrast to the blind reaction of Pope Pius VIII to the news of Martyn’s opus magnum. The Pontiff immediately produced two Bulls claiming that Martyn’s work was ‘a crafty device, by which the very foundations of religion were undermined’. ‘It is evident from experience,’ he said, ‘that from the Holy Scriptures which are published in the vulgar tongue, more injury than good has risen.’ Such facts must be born in mind today as Rome woos evangelicals by telling them that Tyndale and the AV translators jumped the gun as Rome was already preparing superior vernacular versions – based on their Latin texts – for the common man.

Assured by his supporters that his translation would soon be printed, Martyn turned his weary head homewards. His plan was to travel the 1,300 miles to Constantinople on horseback via Erivan, Kars, Etchmiatzin and Erzroom, fording the strong currents of the great Araxes river made famous by Xenophon and skirting Mount Ararat where Noah’s Ark landed. Then, somehow, he had no idea how, he would make for Britain via Malta. It was all in God’s hands.

Sir Gore Ousely, the British resident in Tabriz, prepared Martyn’s route and gave him letters of introduction to the various Persian and Turkish office-bearers on the way. The journey Martyn undertook from Tabriz to Tokat reminds one of Carl May’s multi-volumed adventures of Old Shatter-Hand and his trusty servant Hadji Alef Omar in Wild Kurdistan. Their hardships, however, were works of fiction and wherever they went, they left bloodshed and the cry of ‘Curse the Infidels’ behind them.

Henry Martyn and his trusty, though less capable, servant Sergius had no heavy guns to protect them, though once they had to carry swords as the wilds were swarming with bandits. Their hardships were excruciatingly real but Martyn never forgot that he was an ambassador for Christ. Though many a Turk treated him with harsh contempt, he caused more to believe that they had met a messenger from God.

When Martyn reached Mount Ararat, he marveled how the whole Church of God had once come to rest on its summit. Thinking of Noah, he wrote in his diary, miraculously preserved, ‘Here the blessed saint landed in a new world; so may I, safe in Christ, outride the storms of life and land at last on one of the everlasting hills.’ As Brainerd approached Tokat, he was met by fleeing inhabitants who warned him that the plague had struck in Constantinople and had even caught Tokat in its grip. ‘O Lord, Thy will be done! Living, dying, remember me,’ Martyn prayed and pressed on. He knew he was dying. He reached Tokat on 16 October 1812, and penned his last words:

‘No horse being to be had, I had an unexpected repose. I sat in the orchard, and thought with sweet comfort and peace of my God, in solitude, my company, my Friend and Comforter. Oh, when shall time give place to Eternity? When shall appear that new Heaven and new Earth wherein dwelleth righteousness! There, there shall no wise enter in anything that defileth; none of that wickedness which has made men worse than beasts – none of those corruptions which add still more to the miseries of mortality, shall be seen or heard of any more.’

Being thus at peace with God Henry Martyn experienced no more mortal miseries. He entered into his rest that day aged thirty one, a year younger than Brainerd at his death. It is recorded that Martyn died alone. Whittier claims it was otherwise.

God forbid

That he should die alone! – Nay, not alone

His God was with him in that last dread hour –

His great arm underneath him, and His smile

Melting into a spirit full of peace.

And one kind friend, a human friend, was near –

One whom his teachings and his earnest prayers

Had snatch’d as from the burning. He alone

Felt the last pressure of his failing hand,

Caught the last glimpse of his closing eye,

And laid the green turf over him with tears,

And left him with his God.

In his work amongst Mohammedans, Henry Martyn has been likened to John the Baptist, preparing the way of the Lord. The work he pioneered was not followed up as it should have been by subsequent Christians and now, in many lands, the crescent has encompassed the cross. Martyn’s life and death challenges us with the question, ‘Who will follow in his train?’