Abortion statistics for the UK are eye-watering and outrageous. There are about 220,000 abortions per year. That is 25 every hour, of every day. At least one baby will have been murdered in the time taken to read this short review.

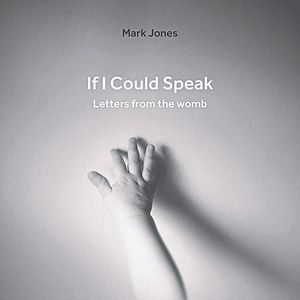

But sometimes the statistics are not enough to capture our hearts. If I Could Speak imagines a series of letters from a female baby in the womb, roughly 20 weeks old, self-named Zoe, whose parents are considering an abortion.

She writes about her development from the fertilised egg, becoming the size of a poppy seed after four weeks, to having a beating heart at five weeks and through the development stages, acquiring a nose, mouth, heart, lungs, brain, and senses until, at nineteen weeks, this baby — now the size of a peach — can hear the voice of her mother.

The text moves between the scientific and the emotional. Zoe imagines how life might be if she is allowed to live and questions her parents’ plan to abort her.

The letter entitled ‘I’m scared’ is the most disturbing as Zoe anticipates in graphic detail the brutality of a surgical abortion. She writes that they will ‘insert instruments to dismember me and extract me from your uterus…. the trickiest part of the abortion is finding, grasping and crushing my head… I will fight. But as a helpless, dependent baby I don’t stand much of a chance’ (p.53). She likens her fate to prisoners at a Nazi death camp. It is gut-wrenching reality.

Zoe’s final letter centres on forgiveness — even though her parents make the decision to kill her in the womb. The last chapter of all is a letter, not from the baby, but from the mother, and you will have to read the book yourself to see what she has to say.

This is undoubtedly a deeply moving book. Giving Zoe a ‘voice’ works well; she is thus enabled to lead the reader through the scientific, moral, and emotional arguments for her right to life. The book ends with gospel hope — even for those who have been involved in abortion.

If there were a criticism, I think it would be that the chapter on forgiveness, including a discussion on moral relativism, is quite complicated. I would also have appreciated some clearer challenge and comfort to those directly affected by the subject matter.

The book is well-produced and laid out with beautiful pictures to keep you turning its pages. While it is not an easy read, it is a good one and I would warmly recommend it.

[This review was originally published in the Affinity Social Issues Bulletin.]

Graham Nicholls

Haywards Heath