In a recent BBC TV programme, The man who made the modern world, Professor Iain Stewart began by asking people in Edinburgh’s George Street whether they recognised a portrait of James Clerk Maxwell.

Virtually none did, even though they were standing right under his large monument, erected in 2008. He is known as Scotland’s Einstein, was a Christian and paved the way for the modern world, with its electrical and electronic devices that we so rely on.

Having spent my working lifetime as a scientist (analytical chemist), I am fascinated by the contribution to modern civilisation which has been made by famous scientists like Faraday (see ET, August 2016) and Maxwell, who were sincere Christians. Their examples should encourage us to be confident in our witness and not fear those who consider belief in God as being feeble-minded.

Early learning

James was born in Edinburgh on 13 July 1831, but spent his first eight years at the family’s country estate, Glenlair in Galloway. Before he was three years old, he was tackling locks with a bunch of keys. ‘Show me how it doos’, he asked, and ‘What’s the go o’ that?’

A general answer would not satisfy him and he would come back with, ‘But what’s the particular go of it?’ He was never satisfied with given explanations and always wanted to work things out from first principles. His education was clearly going to present problems!

By the age of eight, his mother had taught him to learn the whole of Psalm 119 and his great memory enabled him to give chapter and verse for quotes from many other psalms. He was deeply affected when his mother died of abdominal cancer and became very close to his father.

A private tutor was hired, but failed to arrest his attention, and so he was sent to the Edinburgh Academy.

His odd clothes, designed by his father, and his rustic Galloway accent and stutter, together with his weird way of expressing humour, meant he was teased and nicknamed ‘Dafty’. After a mediocre couple of years, he began to blossom and made a couple of lifelong friends who were also to become university professors.

Further education

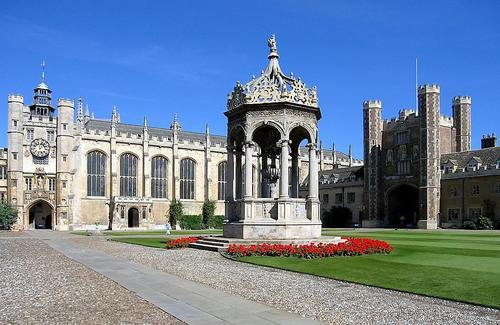

Aged 16, he entered Edinburgh University to read physics and philosophy. His father wanted him to follow his own legal career, but James was determined to choose science and headed for Peterhouse College, Cambridge. He soon transferred to Trinity to read mathematics and physics. His original mind objected to cramming traditional learning, but realised it was an essential preparation ‘for the intelligent study of the material universe’.

Halfway through his degree course, Maxwell summarised a long held belief that, as far as God’s creation was concerned, ‘nothing was to be left unexamined’. There was to be no ‘holy ground’ where Christians should not trespass. ‘You may fly to the ends of the world and find no God, but the Author of Salvation. You may search the Scriptures and not find a text to stop you in your explorations’.

He applied this approach not only to the commonly held theories of his day, but to his own Christian beliefs. Early in 1853 he wrote, ‘I have been reading Archdeacon Hare’s sermons, which are good’. Hare had been a Trinity fellow and returned to preach these sermons in 1839 and 1840.

The first series was published as The victory of faith (1840) and the second as The mission of the Comforter (1846). Hare was a member of the ‘broad church’ party and apparently an Arminian evangelical. Maxwell may well have been prepared by these sermons for the next stage in his Christian development.

Crisis of conscience

Maxwell had been overworking in his third year and, in June 1853, while visiting the home of Rev. Charles B. Tayler, the uncle of a classmate and the evangelical rector of Otley, he fell ill and was kindly nursed back to health.

He said this experience of Christian kindness had given him a new perception of the love of God. He saw clearly from 1 Corinthians 13:8 that ‘love abides, though knowledge vanishes away’. On his return to Cambridge, he wrote to his host: ‘I have the capacity of being more wicked than any example that man could set me, and … if I escape, it is only by God’s grace helping me to get rid of myself, partially in science, more completely in society — but not perfectly except by committing myself to God’.

He was saying he could help himself to avoid sinning by concentrating on his work and spending time with godly friends, but that was not the perfect solution. Only God’s grace could purify him from all sin, through faith in the sufficiency of the blood of Christ.

His classmate later testified that Maxwell showed ‘deep humility before his God, reverent submission to his will, and hearty belief in the love and atonement of that divine Saviour who was his portion and Comforter in trouble and sickness, and his exceeding great reward’.

A change of heart had occurred, and for the next 13 years Maxwell taught Working Men’s classes every week and showed his kindness by helping a fellow student suffering with eye-strain by reading to him from a textbook. He soon afterwards suffered the loss of his father, on 2 April 1856.

Equations

After a brief fellowship at Trinity, when Maxwell published a notable mathematical treatment of Faraday’s ‘lines of force’ connected with magnetic induction, he was appointed professor of natural philosophy at Marischal College, Aberdeen.

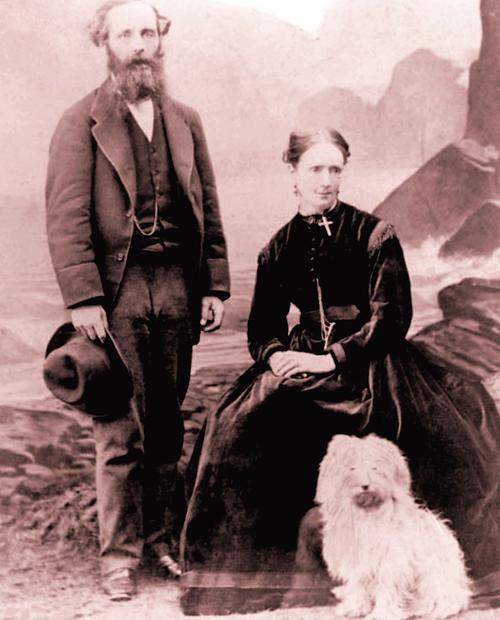

While there, he married the principal’s daughter, Katherine Dewar. He also became an elder in the Church of Scotland. The two Aberdeen colleges merged in 1860, so they moved to London when Maxwell became professor at King’s College, London.

He wrote to his friend Charles Tayler in February 1866: ‘There is a Mr Offord in this street, a Baptist who knows his Bible, and preaches as near it as he can, and does what he can to let the statements in the Bible be understood by his hearers. We generally go to him when in London, though we believe ourselves baptised already’.

He published ‘On physical lines of force’, which predicted that there were electromagnetic waves which could travel at the speed of light, followed by his famous Equations in 1865, which describe the generation and interaction of electrical and magnetic fields, and showed how they can move through space as waves at the speed of light. They formed a vital bridge between Faraday’s laws and Einstein’s relativity theory and later quantum theory.

Maxwell was a man of independent means, and decided to return to his estate in 1865 and complete the outstanding work on the house.

He still found time to continue his father’s custom of leading nightly Bible readings for the family and servants. He kept up scientific correspondence with academic friends such as William Thompson (later Lord Kelvin), which fine-honed his theories and eventually resulted in the publishing of his famous Treatise on electricity and magnetism in 1873.

Faith

In 1876, in correspondence with Rt Rev. C. J. Ellicott, DD, the Lord Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol, about the Genesis account of the creation of light, he expresses great caution about interpreting Scripture by the light of some new scientific discovery.

He wrote: ‘But I should be very sorry if an interpretation founded on a most conjectural scientific hypothesis were to get fastened to the text in Genesis … The rate of change of scientific hypothesis is naturally much more rapid than that of biblical interpretations, so that if an interpretation is founded on such an hypothesis, it may help to keep the hypothesis above ground long after it ought to be buried and forgotten’.

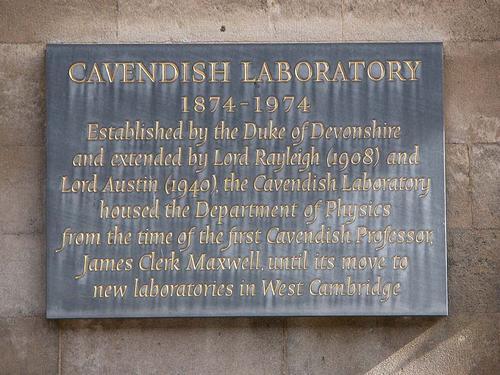

In 1871 Maxwell was pressurised to return to Cambridge to direct the construction and equipping of the now famous Cavendish Laboratory, where the electron and neutron were discovered and which inspired 29 Nobel prize-winners.

In his sixth year as Cavendish professor, he began to be afflicted with the same fatal illness endured by his mother, abdominal cancer. A minister who visited him in his final weeks witnessed that ‘his illness drew out the whole heart and soul and spirit of the man: his firm and undoubting faith in the incarnation and all its results; in the full sufficiency of the atonement; in the work of the Holy Spirit. He had gauged and fathomed all the schemes and systems of philosophy, and had found them utterly empty and unsatisfying — “unworkable” was his own word about them — and he turned with simple faith to the gospel of the Saviour’.

He died on 5 November 1879 and was buried in Parton churchyard near Glenlair. The belief in a Creator God who designed an orderly universe was the bedrock on which his genius flourished.

Einstein, no friend of Christianity, kept a picture of Maxwell on his study wall, alongside those of Newton and Faraday, and declared his work to be the ‘most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton’ (http://www.scotsman.com/news/campaigners-have-theory-for-memorial-to-city-physicist-1-968906).

Legacy

Maxwell’s work was far ranging, and his studies on light and colours led to the world’s first colour photograph using the RGB three-colour method, which is the basis of all our TV and computer monitors.

His formula that frequency times wavelength equals the speed of light underlies the use of all radio and television transmissions, and his calculations predicting that the rings of Saturn were composed of many small particles was later confirmed by astronomers. He was so ahead of his time that people of his day were unaware of his true greatness.

When Jesus walked this planet, he had come in the fulness of time and just at the right time. Yet he was also, in a sense, ahead of his time. He spoke of things yet to come, of ‘signs in the sun, in the moon, and in the stars … for the powers of the heavens will be shaken’ (Luke 21:25-26).

Whereas only clever mathematicians could understand Maxwell’s equations, Jesus spoke plainly, so that ‘the common people heard him gladly’ (Mark 12:37b). Jesus said that he would return to judge the earth and redeem those who belong to him.

The truths Jesus told will never be improved upon or replaced by better theories, and are simple enough to understand. The question is, are we willing to believe him when he says: ‘Whoever believes in him should not perish but have everlasting life’ (John 3:16).

Nigel T. Faithfull is a retired analytical chemist and member of St Mellon’s Baptist Church, Cardiff. In 2012, he published Thoughts fixed and affections flaming (Day One), concerning Matthew Henry.

Sources:

Lewis Campbell & William Garnett, The life of James Clerk Maxwell; Macmillan, London 1882.

Archdeacon Julius C. Hare, The victory of faith, and other sermons; Cambridge & London, 1840; Mission of the Comforter; Gould & Lincoln, Boston, 1854.

Ian Hutchinson, ‘James Clerk Maxwell and the Christian proposition’; MIT IAP seminar, The faith of great Scientists, Jan. 1998.