In October we reach the centenary of the birth of John Murray, and it is fitting to honour so choice a servant of God who has had pervasive influence over the Christian church this century and continues to do so.

Though spending the first third of his life in Scotland, John Murray in America never became a ‘card-carrying Scot’. He did not introduce memories of the Highlands into his lectures or sermons. On no occasion did I hear him mention his experiences in the Great War.

An honour to learn

Just once, when he was lecturing on eschatology, he referred to the Highlands. The text was Matthew 24:28, ‘For wheresoever the carcass is, there will eagles be gathered together’. The context is the visible nature of the return of Christ. All eyes will see him, like lightning fills the sky from east to west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. It will not be a secret knowledge which a select few have who then announce to the ignorant, ‘Lo, here is Christ’. Everyone looking up may see from the hovering eagles that some animal is dead. That is no secret. It cannot be hidden. The world will see the appearing of Christ in the heavens. ‘How often have I seen the eagles circling above a carcass’, he told us. There was that one reference to the Highlands in three years of lectures.

He never used his Scottish education to promote himself, or to climb the ladder of influence in America. He did not have an ambitious bone in his body, and was utterly free of envy. He had studied at Princeton under Vos, Machen and Caspar Wistar Hodge Jr. (grandson of Charles Hodge). What did Britain have, compared to those Americans ? For him it was an honour to learn from and be identified with such men, and to continue to teach in their vital living tradition. He did not write a systematics text-book, believing, like Warfield, that Charles Hodge’s Systematic Theology was unrivalled.

Wartime experiences

His grandfather had been born in the 1780s before the French Revolution. George Washington was just in his fifties. The Wesley brothers were still alive. Grandfather Murray was almost 70 years of age when he married, and his son, Alexander, was born in 1853. Grandmother Murray was alive when John Murray was born on October 14 1898. He was Alexander’s youngest son and one of eight children (6 boys and 2 girls). His grandmother helped to nurse him. She could have said to him, ‘Your grandfather was born in the same decade as Thomas Chalmers’.

In 1914 the War broke out. His brother William joined the Navy. Donald went to France with the Seaforth Highlanders. Tommy went to the Dardanelles with the Camerons. Tommy was a very godly boy who never said ‘No’ to his father. There was a particularly long and affection farewell to him, the thick-set and softly spoken father putting his arms around 20 year-old Tommy’s neck; ‘Good-bye Tommy. I’ll never see you again’.

When the 5 foot 6 inch John was 18 years and 179 days old – a mere schoolboy – he was called up and joined the Black Watch – the Royal Highlanders. Within six months he was fighting in France. Mr. Murray did not know the exact year when he was regenerated, but those months revealed his new disposition towards God, as the conduct of men at war grieved him. He sought quiet spots to read and pray. He heard that Donald was missing in action and he sought more information, trying to trace where his brother was buried, but it was all to no avail. He came to believe that Donald had been wounded and had fallen into a shell-hole. Death was all around him.

Turning point

Eight months after his arrival in France there was a prolonged battle, the turning point of the war. It was July 1918 and an Allied offensive drove back the German army. He had the exhilaration of seeing waves of kilted Highlanders, bayonets fixed, moving forward to the sound of the pipes, taking one position after another. He had been promoted to lance-corporal and was leading a group of men as young as himself. The fighting went on through the day and night and they slept standing up. It was in this offensive that he was struck with a piece of shrapnel which destroyed his right eye. He was nineteen years of age when he was invalided out of the army.

Princeton

He entered the University of Glasgow where he obtained his M.A. in 1923 and, believing he had been called into the ministry, he studied under the leading preachers in the Free Presbyterian Church.

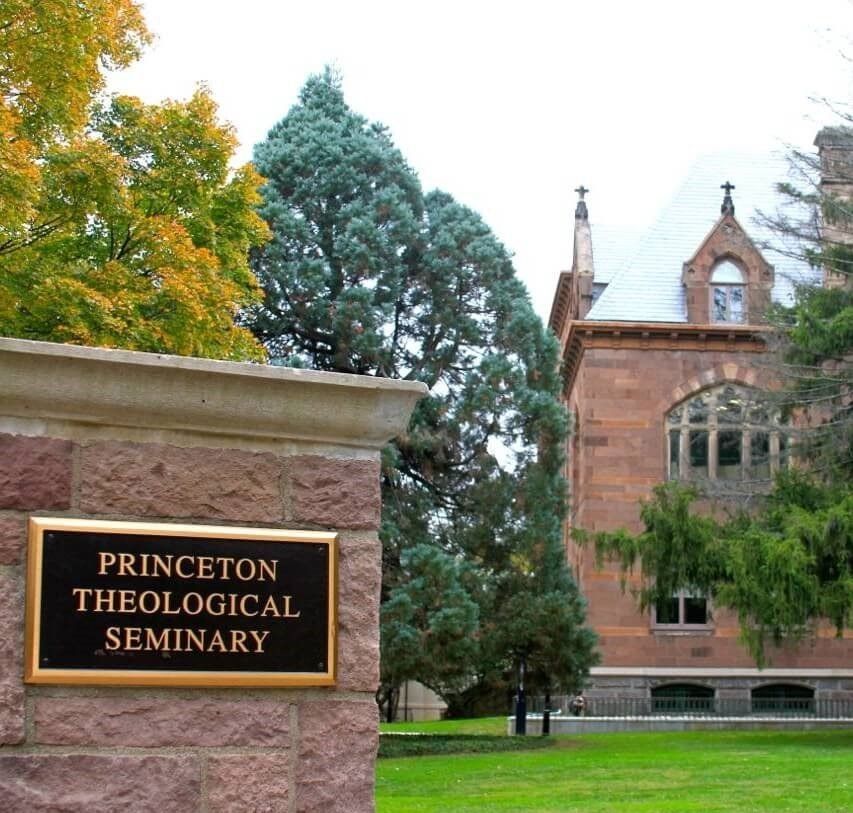

His gifts were speedily recognised and the church decided to send him to Princeton in the summer of 1924 to equip him to become a future theological tutor. This was the first of his many transatlantic crossings, and he disembarked in New York, but having few documents he was made to wait on Ellis Island for hours. Finally Princeton Seminary was contacted and one of the staff came to Ellis Island to collect him. That was the beginning of forty years spent in the USA.

B.B.Warfield had been dead for three years and, although the Seminary was still largely in conservative hands, the United Presbyterian Church in the USA was drifting into liberalism. The 225 students were a mixed bunch, as were the Seminary’s trustees. Mr Murray fitted in to the whole life of Princeton with ease. He had a Highland sense of humour. I heard some good stories from him. At Westminster’s Dining Club he would be asked after dinner, before devotions, ‘Have you a story for us tonight Mr Murray?’ He frequently did. The student Benham Club which he joined at Princeton made it a rule that a member had to tell a funny story on being asked, or pay a fine of 25c.

Yet there were clear boundaries to his humour. We went to Princeton Seminary one evening in 1962 at the 150th Anniversary Celebrations, when Karl Barth gave three evening lectures. Men enjoy trying to tell jokes in their second language, and Barth was no exception. In one he said that the third person of the Godhead should be referred to as ‘Spirit’ rather than ‘Ghost’ because of spooks. The audience laughed at his jokes and this was remarked on in the car returning to Philadelphia. ‘I did not laugh’, said Mr Murray. He always avoided student Stunt Night because the humour, especially the impersonations of the lecturing staff, could get out of hand.

Westminster Seminary

When Princeton chose to bring in more liberal lecturers, Westminster Seminary was started and Gresham Machen approached Mr Murray, who for a year had been lecturing at Princeton under Caspar Wistar Hodge, to come to Philadelphia and teach there. It was a time when he was torn between the call of Scotland and the needs of the new Seminary in the USA, but on 15 September 1930 he accepted Dr Machen’s invitation and remained at Westminster until 1 January 1967.

I arrived at the Seminary in 1961 having never seen a photograph of Mr Murray. I had read Redemption Accomplished and Applied, and still remember sitting on Pontypridd station waiting for a Cardiff train one Saturday night reading the chapter on sanctification, and being greatly moved by it. I expected to meet someone who looked like Charlton Heston, tall and handsome, because the writing had such nobility and beauty. I did not guess that the short man who joined us at lunch one day was John Murray. He had moved out of the Seminary that summer, having lived there in rooms at the top of Machen hall. The growth of the student body meant that he needed to move into the community of Glenside. This spared him being asked at meal-times the meaning of different verses in the Bible (‘Are you being asked to preach on this verse?’ he would inquire), but we lacked some social contact with him which earlier generations had enjoyed.

No greater vocation

I took everything he offered, the compulsory studies in theology from the Doctrine of God through to Eschatology, as well as all his options, Covenant Theology, Romans, the Westminster Confession, Sanctification. He never lectured on baptism, but you were expected to buy his book on that subject and sit a one hour exam on it. He did not teach his courses on Old Testament Biblical Theology or Christian Ethics while I was there, and that was my loss. I thought it all was beautiful. I felt there could be no greater vocation than to teach theology just as Mr Murray taught it. He was the man most full of God whom I have ever met. He drew you, so that if you saw him you wanted to go to him and speak with him. What delight it was to have his arm linked through yours as you walked around the Seminary’s fine grounds.

Yet his holiness alerted you and made your words cautious. Having him in your home you wanted the little girls to be on their best behaviour, and you were so careful about how you phrased your questions. I remember once in Scotland, towards the end of his life, saying to him, ‘Mr Murray, do you covet anything from Westminster?’, and then, immediately being covered in confusion. What was I asking him? Did he break the tenth commandment? But he answered me as carefully as ever. ‘I would covet the library at the Seminary’.

Logan Murray was born to him and his wife Valerie in December 1968, six months after our second girl. I was away the Saturday evening Mr Murray arrived to preach for us, so my wife Iola and Mr Murray had a time discussing babies. ‘It is remarkable’, she said, ‘when they are born and you see their tiny hands and feet, so perfect. It’s a miracle’. Mr Murray paused; ‘Yes’, he agreed, ‘but not in the technical sense of the word’.

Puritanism

His lectures began with prayer, which he always took. They were deeply reverent, centred on God and his inestimable majesty, our access being only by our blessed Redeemer. They emphasised our need for God’s help to achieve anything in our lives. Whenever I read John Calvin’s prayers, he always prays with a Scottish accent! Mr Murray’s teaching was lucid and exegetical, utterly persuasive, making Reformed doctrines live. There was mercifully no time for questions during the class. He lectured at a speed at which one could write down virtually all his words, though it was not dictation, and not quite preaching either.

A Seminary is blessed if it has just one man like that. It is absolutely crucial to have someone who is apart, and can inspire, and, without striving, bring the reality of another world to the life of a school. In many ways, Mr Murray and his Puritanism were not appreciated by the student body. Even those who loved him did not always understand what his whole life was saying, and why he acted as he did (and he was deeply loved by staff, students, and the whole of his denomination, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church; I have not met a man so transparent in his life who could inspire such affection). But that has been the case with other Christian leaders, with Spurgeon, Machen and Lloyd-Jones. I think of the Corinthian congregation. A letter arrives from the apostle Paul, so utterly different from anything they have seen before; it was convicting, healing, warm, holy, sanctifying, and enlightening, leaving them with so much to consider. Mr Murray, and men of God like him, are like that epistle.

Generous and thoughtful

I never met anyone so free from any sense of self-importance, generous in giving away his books to the student body at the Seminary, financially thoughtful to others in need. If he chaired a meeting at which you were speaking, how effusive he would be in his praise! When people wrote to him with their questions from all over the world, he would spend time in long, hand-written replies, scribed in beautiful script with his fountain pen and black ink. He would accept invitations to preach from the smallest congregations in the most remote places. He had no thought of a crowd. How sensitive he was to his own sin, and modest about his own achievements!

I saw him in Badbea, the house in which he was born, a week before he died. He was haggard and told me I should read and pray for five minutes. I prayed like a little boy, overwhelmed by the occasion, and have regretted my prayerlessness since. He shook my hand; ‘Good-bye, sir’, he said. Those were his last words to me.