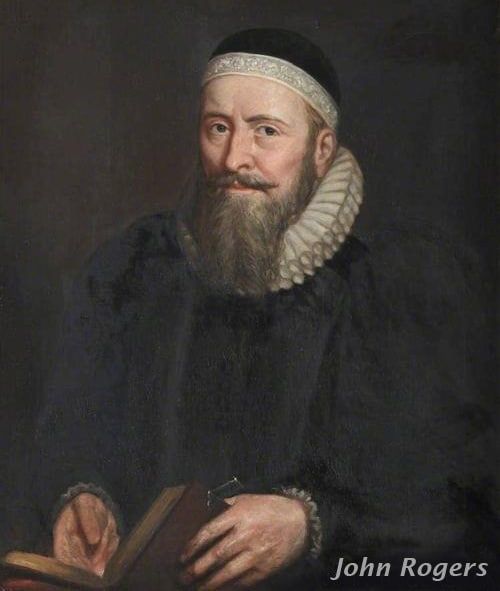

John Rogers was born in 1500 in the hamlet of Deritend, since swallowed up by modern-day Birmingham. He matriculated to Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, around 1521 and took his BA in 1525.

Nicholas Ridley was a contemporary. The Bishop of London’s registry confirms Rogers’ appointment as Rector of Holy Trinity, in the City of London on 26 December 1532.

God’s providence

Rogers left England for Antwerp in September 1534. Unlike those (such as Barnes, Coverdale, Frith and Tyndale) who fled England in fear of their safety, Rogers was still in good standing with the Roman Church.

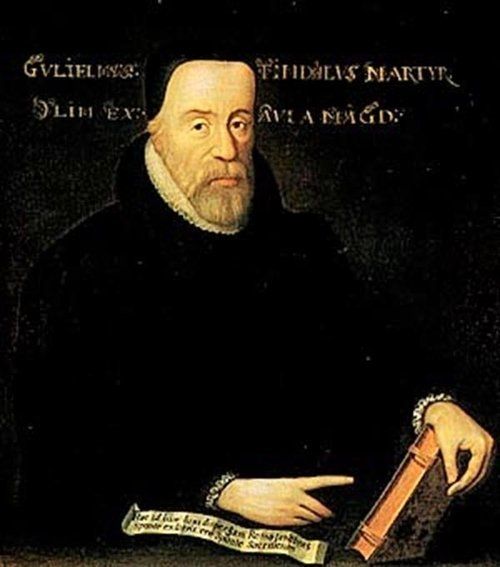

Various reasons for his departure have been advanced. He may simply have been attracted by the ‘new learning’ that was abroad. What is clear is that, in the providence of God, he met William Tyndale at Antwerp in the autumn of 1534.

As they discussed the Scriptures, Rogers came to a saving knowledge of the gospel. John Foxe confirms the timing of his conversion, recording his statement to Gardiner in January 1555, that he had not been a member of Gardiner’s ‘false church’ for twenty years.

Profitable labour

As Foxe relates, a close bond was established between Rogers, Coverdale and Tyndale in Antwerp, as Tyndale gave himself to ‘that painful and most profitable labour of translating the Bible into the English tongue’.

In Rogers, William Tyndale found a trusted friend. But the comfort afforded by that friendship was short-lived.

Tyndale was arrested in May 1535 and martyred at Vilvorde on 6 October 1536. The martyr’s love of God, and his noble work of translating the Word of God into the vernacular, had a profound effect on Rogers. The completion of Tyndale’s work dominated the rest of Rogers’ life.

Pseudonym

Carrying Tyndale’s work forward involved conserving much of his unpublished material. When the English Bible appeared in 1537, it included hitherto unpublished translations from Tyndale’s pen, particularly the Old Testament books from Joshua to Chronicles.

The Bible was printed, it did not bear the name of John Rogers; instead the pseudonym ‘Thomas Matthew’ was used. That it was, in fact, the work of John Rogers was attested by John Bale in 1548 and John Foxe in 1559.

When the Privy Council put Rogers under house arrest in August 1555 they described him as ‘John Rogers, alias Matthew’.

John Rogers sought to preserve the integrity of Tyndale’s translation. It was his great ambition to edit and publish the manuscript material, which might otherwise have been permanently lost.

Perhaps he hoped that by using a pen name, the credit would rightly fall to Tyndale. Certainly, in faithfully completing the task begun by another man, he risked his own life.

High esteem

Among the prefatory material in the Matthew Bible, there were further pointers to the high esteem which Rogers accorded to the Word of God. Following the contents pages and calendar, came ‘An Exhortation to the Study of Holy Scripture’.

Interestingly, at the foot of the page were two flourished capitals, ‘J. R.’, direct evidence of the hand of Rogers in the volume.

The original publication of the folio volume running to 1,110 pages was financed by Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch, of the Grocers’ Company in London and the Merchants’ in Antwerp.

In the autumn of 1537, events unfolded leading to the Royal proclamation by Henry VIII, resulting in the first authorised Bible in English history. The royal approval appeared at the foot of the title page, lying outside the woodcut border: ‘Set forth with the Kinges most gracyous lycece’.

Cranmer was delighted with the translation, and sent a copy to Thomas Cromwell. He not only recommended the work, but emphasised its dedication to the king

Dedication and scholarship

In his dedication Rogers wrote: ‘It is no vulgar or common thing, which is offered to your Grace’s protection, but the blessed Word of God, which is everlasting and cannot fail, though heaven and earth should perish.

‘So precious a thing requireth a singular good patron and defender, and findeth none other unto whom the defence thereof may so justly be committed as unto your Grace’s majesty.’

This was not merely a ploy. Several months earlier, at Vilvorde, Tyndale had prayed for God to open the king of England’s eyes; surely that prayer was answered in a glorious manner.

The work from beginning to end depended on the intervention and blessing of God. He it was who raised up men dedicated to the translation and dissemination of the sacred Scriptures. He alone could prosper that project and by his grace give men a genuine heartfelt love of his Word.

The high standard of scholarship involved cannot be denied. Even the notes contained in the volume confirm its outstanding quality. Throughout the Matthew Bible, thoroughness and extreme care remain its hallmarks.

Imputed righteousness

During the late 1530s, Rogers married Adriana de Weyden of Antwerp. Foxe noted that she was ‘richly endowed with virtue and soberness of life’.

He befriended Melancthon in Wittenberg, translating some of his books into English. Besides supplying further evidence of his linguistic ability, this helps to establish that Rogers’ grasp of reformed theology was solid.

This is also obvious in the preface to the Matthew Bible: ‘the Law [of Moses] was given that men might know sin and that they are sinners. Yet this Law was given to the intent that, sin and the malice of men’s hearts being thereby the better known, men should the more fervently thirst the coming of Christ which should redeem them from their sins.

‘In the New Testament therefore it is most evidently declared that Jesus Christ, the true Lamb … is come … to reconcile us to the Father, paying on the cross the punishment due to our sins; and to make us the sons of God.

‘For that faith is the gift of God … By that faith Christ’s Father counteth us for righteous and for his sons: imputing not our sins unto us through his grace’.

Martyrdom

The death of the godly King Edward VI in July of 1553, signalled a dark period ahead for the Reformation in England.

Mary was proclaimed Queen on 19 July, and the following month saw Rogers preaching the gospel in a sermon at St Paul’s Cross which occasioned his dismissal. His subsequent persecution and martyrdom served as an example to many of the English Reformers, such as Latimer and Ridley.

At his trial, his inquisitor Gardiner pressed him on the issue of the Roman Catholic doctrine of the Mass. After hearing an explanation of transubstantiation, the Reformer was asked for his view; he replied in one word: ‘False’.

On 4 February 1555 he was taken to be burned to death at Smithfield. Asked by the city Sheriffs to revoke his teachings, he said: ‘that which I have preached, I will seal with my blood’. In the fires of the Marian persecution, he openly displayed that faith which ‘quenched the violence of fire’ (Hebrews 11:34).

The cruelty of his persecutors is historically documented, but so too is the special grace of God to Rogers. Eyewitnesses reported that he seemed to wash his hands in the flames before yielding up his life.

Relevance

What relevance does the life and work of John Rogers have in this modern age? Surely the lessons are as follows.

Firstly, there is a world of difference between true and false religion. The former glorifies the living God, provides eternal salvation in Jesus Christ, and it is rooted and based on the inerrant God-breathed Scriptures.

False religion, by contrast, glorifies man, leads to a lost eternity, and is based on the imagination of man.

True religion gives the glory that is due to Christ alone. False religion robs Christ of his central place in the work of salvation and denies that he is the Head of the Church.

Secondly, the gospel of Jesus Christ is an ‘old path’ which is straight and narrow, and ‘few there be that find it’ (Matthew 7:14). It stands in distinct contrast to the man-centred religion that abounds in our modern world.

The Scriptures that John Rogers fought so admirably to translate and publish remain the only route to knowing God and salvation. The false religion Rogers opposed at the time of the Reformation continues unabated today.

Now, as then, the root of its wickedness lies in its rejection of the Word of God.