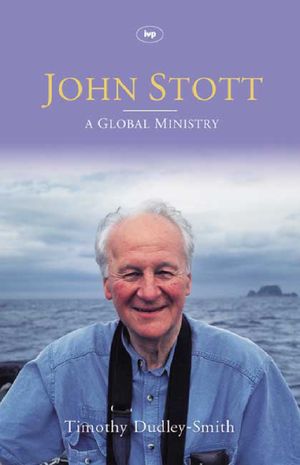

Author: Timothy Dudley-Smith

Publisher: IVP

514 pages

Purchase from: Eden

(£16.35)

This article reviews the second volume on the life of John Stott written by Timothy Dudley-Smith.

The book traces his ministry beyond the confines of All Souls Church in London, where his ministry as Rector began in 1950, into far-flung countries to which his vision and boundles energy transported him.

The result of much painstaking research, based largely upon Stott’s diaries and impressions, the book is extremely well-written. It does, however, becomes tedious in parts due to the inclusion of trivial and extraneous material.

Another problem I have is a happy one: John Stott is still alive! But, as that notable biographer Roy Jenkins recently commented: ‘Best biographies are posthumous biographies’.

Critical appraisal

Dudley-Smith is a close friend of Stott’s and this prevents him giving a critical appraisal of his subject. Indeed, in his last chapter he likens John Stott to the apostles John and Paul among others (p. 426).

How can his friend be unharmed by such adulation? How can Stott, who read the manuscript (p. 13), have failed to censor this?

Critical appraisal, however, is surely required, because John Stott’s influence in giving evangelical Anglicans a new direction in the sixties, and his willingness to compromise the evangelical position in an uneasy alliance with non-Evangelicals, has caused much dismay and disappointment.

Outstanding gifts

John Stott was capable of enormous expenditure of energy, and the reader feels rather like the reporters who attempted to follow Henry Kissinger in his travels. He is a man of outstanding gifts and iron discipline, and has accomplished in one lifetime what five men would have found difficult to achieve — in preaching, writing, organising and travelling.

The Evangelical Alliance meeting on 18 October 1966, when John Stott as chairman had a confrontation with the speaker Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, is given fair and accurate treatment.

The author, however, is wrong to suggest that this public disagreement brought about the recasting of the Puritan Conference as ‘The Westminster Conference’ (pp. 69f).

This change was precipitated by the publication, four years later, of Growing into Union, in which J. I. Packer and Colin Buchanan collaborated with an Anglo-Catholic and a liberal scholar in producing ‘Proposals for Forming a United Church in England’.

But Dudley-Smith is surely right in stating that ‘the National Evangelical Anglican Congress of 1967 was to prove a bigger cause of division’ (p.70).

Keele Congress

The Keele Congress, masterminded by John Stott and planned before October 1966, proved to be a turning point in evangelical Anglican thinking. It did more to alienate non-ecumenical and Free Church Evangelicals than anything else.

The acceptance of comprehensiveness in the Anglican Church was a departure from the position previously held by evangelical Anglicans. It paved the way for a ready, if not eager, participation by Evangelicals in every facet of Anglican Church life, without the burdens of a guilty conscience and an unsustainable position.

After Keele, John Stott placed increasing emphasis on what he believed to be the social and political implications of the gospel. At Keele he had renewed contact with a young theological student, Ted Schroder from New Zealand, and later invited him to All Souls as a curate.

His influence on Stott was profound (pp. 27ff). He felt that Stott failed to apply the gospel to the modern world, and told him so.

Because of its timeless nature and man’s permanent fallen condition, the gospel always has a contemporary ring about it. But Schroder was not satisfied with this; he wanted a more specific application to social and political issues.

World agenda

One observer, returning to All Souls in 1970, discovered that John Stott’s emphasis had changed. He ‘addressed himself more thoroughly and fully to some of the items on the world agenda’ (p. 29). Very unlike the apostle Paul!

From this time onwards his preaching focused increasingly on contemporary social and political issues as well as the biblical message. He made himself much more aware of cultural trends, and helped to establish a series of ‘London Lectures in Contemporary Christianity’ at All Souls (pp. 168-171).

John Stott had become convinced that Evangelicals were out of touch with the modern world. There was need to listen, he believed, not only to what the Bible said but to what the world was saying: ‘double listening’ he called it.

In criticising Evangelicals for their deficiencies, Stott seems not to have appreciated that the problem lay with the ‘quietist’ influence of the ‘Keswick Message’ upon evangelical life from 1875 onwards.

He seemed to think that a lack of social awareness was a basic flaw in Evangelicalism itself, which needed to be corrected by the introduction of a socio-political dimension into evangelical preaching.

The history of Evangelicalism prior to 1875 should have taught him that the evangelical message alone had been the greatest force for social reformation this country has ever known.

Lausanne

At the Lausanne Congress on World Evangelisation in July 1974 he pleaded for ‘greater social consciousness’ (pp. 211f). This should be the background to our evangelism, he argued.

He welcomed the place given by some to ‘socio-political involvement’ alongside evangelism. The Lausanne Covenant, which owed much to his drafting skills, signalled a shift in evangelical understanding of the relationship between evangelism and social concern.

This later led to a sharp disagreement between Stott and American Evangelicals represented by Billy Graham at the Lausanne Continuing Committee in Mexico City in 1975.

Stott was not satisfied that the Christian should merely be made aware of his responsibilities as a citizen of the kingdom of heaven living in this world — which is the biblical emphasis.

The Church, he felt, should address the social issues of the day. This conviction brought him to establish the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity in 1982.

Courses were arranged in ‘thinking Christianity’, dealing with such subjects as war and peace, work and unemployment, race and gender, medical and sexual ethics and the care of the planet.

Contemporary Christianity

Resigning as the Rector of All Souls in 1970, John Stott was freed to extend his world-wide ministry. He drafted the Manifesto of the Manila Conference in July 1989, successor to Lausanne, and sought to combine social as well as evangelistic emphases.

This social preoccupation made him more acceptable in ecumenical circles, but weakened his evangelistic impact. Prior to 1970 his message in university missions had been strongly evangelistic; in the 80s and 90s he was much more in demand for his addresses on ‘Contemporary Christianity’ as he called it.

Much of his thinking on social matters is found in his book Issues Facing Christians Today (1984). He writes on industrial relations, employment, ecology, global economic inequality etc.

He had some reservations about his competence to pronounce on such subjects. One of his study assistants, Paul Weston, commented: ‘The whole area is outside his experience and, I suppose, his area of expertise’ (p.339).

It was indeed, and Dudley-Smith lets him get away with it! Of course, ‘his desire, and aim, was to bring biblical principles to bear on the issues of today’.

But whether there is such a thing as a biblical view on such issues is doubtful. In any case, if our object is to persuade the world to behave in a Christian fashion without first becoming Christians, we become guilty with William Temple of a major heresy.

Lost in the jungle?

On one of his overseas trips, John Stott got lost in the Amazon Jungle (p.318). Birdwatchers beware! The reviewer has the distinct impression that Stott’s involvement in social affairs has become something of a jungle in which he has lost his way.

In a dialogue with the liberal David L. Edwards, published in 1988 under the title Essentials, John Stott was unwilling to be definite on the issue of eternal punishment. He suggested that ‘Scripture points in the direction of annihilation’ (p.352) and conditional immortality.

Dr J. I. Packer later charged him with a wilful rejection of ‘the obvious meaning of Scripture’. Dudley-Smith points out that Basil Atkinson, John Wenham and Philip Hughes also held Stott’s view, and concluded that ‘he was in good company’ (p.353).

But if these men were rejecting ‘the obvious meaning of Scripture’, as we believe they were, then he was in bad company, not good!

Nothing undermines the fervent preaching of the gospel so much as disbelief in the biblical doctrine of hell. In this matter Stott has fallen short of holding fast an essential of the faith.

In 1971 John Stott began to apply his book royalties to an Evangelical Literature Trust, for the benefit of pastors and theological students in over one hundred countries in the developing world.

Stott’s literary output has been enormous. Valuable commentaries and expository works have helped many Christians worldwide. The author has provided a comprehensive account of the life of an influential man.

Paul Cook