Born in 1918, and now almost eighty years old, Billy Graham straddles the century. He has been described as a twentieth-century phenomenon.

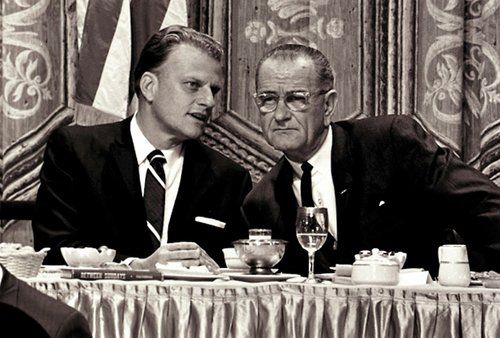

Billy Graham is the product of Bob Jones University, Florida Bible Institute and then Wheaton College, Illinois. He was ordained as a Southern Baptist pastor and soon after became the first ‘evangelist’ of ‘Youth for Christ’. In 1948 he became president of Northwestern College, Minneapolis. Propelled by the Greater London Crusade of 1954 into world fame, he later founded the ‘Billy Graham Evangelistic Association’ (BGEA). This depends upon the same principle of teamwork which Billy Graham has always used in his crusades both ‘on stage’ and behind the scenes. At one time a thousand employees were based in offices around the world. Hundreds of thousands of letters are answered every year. In 1966 he initiated the World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin and this spawned other world congresses. He has mixed with the world’s top statesman, had spiritual conversation with Winston Churchill, been received by the Queen a dozen times and been the spiritual confidant of every American president from Eisenhower onwards.

What many readers of this autobiography will want to know is how Graham, at the age of 80, and with many long years of experience behind him, summarizes his message. Those who persevere in reading this autobiography, in spite of its rather uninspiring style, will find such a summary at the end of the book where Billy closes with this appeal to his readers ‘ … God loves us. He yearns to forgive us and bring us back to himself. He wants to fill our lives with meaning and purpose right now … Moreover, God has done everything possible to reconcile us to himself … In God’s plan, by his death on the Cross, Jesus Christ paid the penalty for our sins … Now God freely offers us the gift of forgiveness and eternal life … God has done everything possible to provide salvation. But we must reach out in faith and accept it …’ (pp. 727-728). This is Billy Graham’s gospel — Jesus has done his bit, now you do yours. This ‘gospel’ has run swiftly in the earth. It has been well received, not only by many who call themselves evangelicals, but also by liberals, Roman Catholics, Orthodox and many others. As Rose Kennedy, matriarch of the influential Kennedy dynasty, said to Graham, ‘You know, I often listen to you. Even though we are Catholic, I have never heard you say anything we don’t agree with in the Bible’ (p. 401).

One typical page says that in Korea (1952), ‘many hundreds responded to the Invitation to receive Christ and be converted’ (p. 196). They became part of the hundreds of thousands who between 1947 and 1997 ‘went forward’.

Over the past fifty years Billy has travelled the globe several times over. He has conducted crusades in cities in North Korea, China, Russia, India, Australia and Colombia as well as in New York, London, Chicago, San Francisco and dozens of other cities all over the world. Millions have heard him live. Scores of millions have listened in to him on television, radio, film, land-link or satellite-link. Peace with God, and How to be born again have become world best sellers. Multitudes have been reached by Decision magazine and Christianity Today.

Yet Billy’s story will raise questions in the minds of many discerning readers. Everything in his garden is rosy. He finds spiritual hunger in nearly every politician, hobo and journalist he has personal dealings with. Hardly anyone is indifferent to the spiritual.

The sometimes profane President Johnson is a case in point: ‘LBJ had a sincere and deeply felt, if simple, spiritual dimension. But while he was serious about it, I could hardly call him pious. Yet I was beside him many times as he knelt by his bedside, in his pyjamas, praying to One mightier than he. I saw strength in that, not weakness. Great men know when to bow’ (p. 404). And so from crusade to crusade we go, from invitation to invitation, from big name to big name, from success to success. There are few failures to report.

Once or twice is it difficult not to sympathise, one occasion being when Billy describes a serious intellectual and spiritual crisis which occurred early in his ministry. A close colleague was succumbing to modernism and tried to drag Billy Graham down with him. Billy wrestled and agonized inwardly, but then triumph came and he embraced the perspective of an authoritative Scripture (pp. 135 -139). It was soon after this that he conducted his Greater London Crusade, one which, maybe more than any other, produced true converts as well as the usual spiritual wreckage and confusion.

There can be no doubt that God, in sovereign mercy, has been pleased to truly save many sinners through Billy Graham’s ministry. We know that God can use whatever instrument he pleases to perform his sovereign will. However, in the wake of Graham’s ministry there is much spiritual wreckage. There are undoubtedly many thousands around the world who feel that they are ‘born again’ and on the road to eternal glory because they made their ‘decision’ at a Billy Graham rally. We find them everywhere, armed with their ‘testimony’ and waving their decision card, yet their life is evidence that there has been no true work of grace. Many no longer attend any church and live in sin and corruption, but they still believe they are ‘saved’ because they made their decision. This is the devil’s tool and he knows how to use it. Why then should he oppose such evangelistic methods as those used by Billy Graham?

Wreckage is the greater part of what can be expected from his ministry after reading the retrospective account of his teenage conversion. ‘My tailor friend helped me to understand what I had to do to become a genuine Christian. The key word was do. Those of us standing up front had to decide to do something about what we knew before it could take effect. He prayed for me and guided me to pray. I had heard the message, and I had felt the inner compulsion to go forward … the final issue was whether I would turn myself over to [Christ’s] rule in my life’ (p. 30).

There is in Graham’s gospel challenge and testimony a deep naïveté about the grip of sin on human nature, and its extension to every faculty of our being. Not only are people sinful, they are spiritually dead. The will is in bondage and the mind is hostile to God’s law and gospel invitations alike. If anyone is ever to be saved it can only be because God has deliberately picked them out of the mass of humanity on the grounds of his grace alone. Their sinnerhood as well as their sins can only be paid for by the sacrifice of one sinless substitute, Christ alone. On the grounds of Christ’s merits and death his people receive faith and repentance, but only after receiving a new nature to exercise those graces. Only in that context has the sinner a work to do, to believe on Christ (John 6:29).

Billy Graham need not be ignorant of all this because it is in Scripture, but he never owns up to being troubled with such formulations. He has retained the name ‘evangelical’, but has skilfully avoided the contempt which many people have for those who bear the name. He has never separated from those who have embraced sacramentalism as a way of salvation. He has prayed with Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox, shared platforms with their bishops, exchanged pleasantries with the pope. His one policy has been ‘to let the Catholic bishops see that my goal was not to get people to leave their church; rather I wanted them to commit their lives to Christ’ (p. 163).

Billy Graham’s gospel is not then the biblical gospel. It is not the gospel of the apostle Paul, nor of the Reformers or such men as Jonathan Edwards or Asahel Nettleton and many more. It is the man-centred gospel of Charles Finney. Billy’s is a naïve, evangelistic decisionism, which can be so disarmingly simplistic.

His message has been nonetheless deeply affecting to generations dislocated by two world wars and menaced by the atomic bomb. Here is a clean-living, winsome family man, with a rugged personality and a black-and-white message from the Bible. Here is a powerful communicator, backed up by a dedicated team of enthusiasts and ready to seize the opportunities to get his message across. He preaches to a generation that revels in the illusory glow of the Waltons. He appeals to the wistfulness of a post-war world shattered by unimaginable cruelties. Naïveté, simplicity and certainty are all that it wants and Billy Graham supplies all that, with the promise of heaven written on the back.

What we learn from this autobiography is that preaching the message which the world wants to hear can bring fame and honour beyond imagination to those gifted enough to do it well, but preaching the gospel faithfully is profoundly theological and profoundly unpopular. The tragedy is that this autobiography only teaches us the latter by negative example.

Roger Fay