You might think that there is absolutely nothing to link the death of Jesus Christ with the death of Lenin in 1924. But there is just one thing: in both cases, the authorities of the day were troubled over their respective bodies. More than that, in both cases the question of the body has been a central issue ever since.

When Lenin died in January 1924, most Soviet leaders opposed the idea of preserving his body beyond a temporary period of public display. He himself had asked to be buried.

However, the bitterly cold Russian winter provided some protection for the corpse and, as the huge crowds queueing to pay their respects showed no signs of abating, the Soviet leaders mulled over the idea of preserving the body for the longer term.

Moscow mausoleum

And so a team of anatomists, biochemists and surgeons was tasked with the job of maintaining Lenin’s body. They did so in their own designated institution, the Centre for Scientific Research and Teaching Methods in Biochemical Technologies in Moscow. The institute was funded by the state until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Since then, it’s been maintained by voluntary funding.

All of this means that, apart from a brief period during the war, when Lenin’s body was evacuated to the Urals for safe-keeping, he’s been on public display in a cold, marble mausoleum, in Moscow’s Red Square, ever since.

As the years pass by, it seems increasingly macabre not to give Lenin a decent burial and be done with it. But, on the other hand, it has become increasingly difficult for Russian people to break with years of tradition.

When Vladimir Putin became Russian president, he faced the vexed question of what to do with Lenin’s body. Perhaps somewhat predictably, he decided that things should be left as they are, at least for the time being.

The trouble with burying Lenin would be that it would symbolise an irreversible severing of the ties between Russia as it is today and its revolutionary past. Almost literally, it would be the final nail in the coffin of communism.

Different era

In short, it would send out a message to a remnant of Russian people still cherishing the ideals of communism that communism has failed for good, never to be recovered. In a remarkably frank admission, Putin himself stated that burying Lenin would have said to them that ‘they worshipped false values, that their lives were lived in vain’.

All of this raises questions that demand an answer; questions like, ‘If communism is worshipping false values, what are true values?’ And, ‘What does a life that is not lived in vain look like?’

Clearly, Russia is not the country Lenin knew. Neither is it the country he would have wanted it to become, or ever envisaged it becoming. It may seem cruel to say it, but, if Lenin could see the Russian oil magnates and oligarchs today, he would be turning in his grave (that is, if he was in one!).

Not only has Russia moved on, but the process of preserving Lenin’s body has moved on too. A new generation of scientists has learned how decomposing parts of skin and flesh can be replaced with plastics and other materials that give colour and suppleness to the body.

At the age of 146 years, Lenin’s body looks far better today than it did almost 100 years ago when he was alive and beginning to approach the end of his life.

An honest assessment of the situation leads to the conclusion that preserving Lenin’s body has become a substitute for preserving his ideas. Russia can no longer honour its hero by standing by his principles. Instead it will honour all that is left of him — his remains. And even his remains are being imperceptibly replaced by man-made substitutes.

Body gone

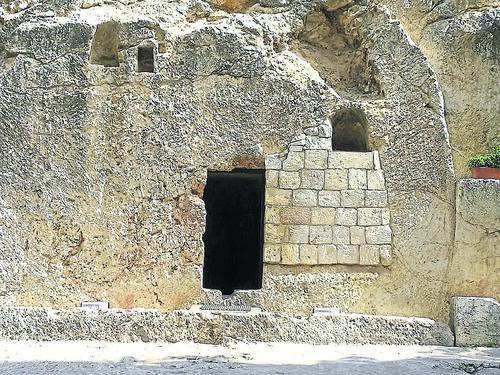

As far as Jesus Christ is concerned, the authorities also had a problem with his body, but a wholly different problem — despite the huge boulder and Roman guards at the tomb, Christ’s body had gone.

The Soviet leadership had Lenin’s body and pondered what they should do with it. The Jewish leadership did not have Jesus’ body and pondered what they could do about that. As they saw it, their lives rested upon getting hold of it and presenting it to the world.

At least the Soviets hit upon a solution which worked for them. The chief priests never had a chance: Jesus had risen bodily and there would never be a corpse, either to bury or to preserve! The best they could do was to bribe the guards that the disciples had stolen the body (Matthew 28:11-15).

Of course, anyone hearing that rumour and then seeing those same disciples preach the risen Lord Jesus fearlessly and witnessing their readiness to die for their Saviour could only have drawn one conclusion, that he really must have risen from the dead. Why would anyone die for a lie they themselves had invented?

Meanwhile, if the chief priests in New Testament times saw their lives as resting on securing the body of Jesus, Christians would say that their lives rest on the fact that there are no physical remains of Jesus anywhere on earth.

Resurrection

And so, what seems to link the death of Jesus and the death of Lenin turns out to be the very thing that separates them. It is the question of the body that separates Christianity, not only from communism, but from all other philosophies and religions.

Put simply, ‘There is no body here!’ The statement, ‘He is not here, he is risen’, is as true today as it was on the first Easter Sunday. Great ideas may come and go; leaders like Lenin live and die. But the One who promises eternal life to all who believe in him has no mausoleum and no grave. Jesus is alive!

Paul Mackrell grew up in Hampshire, but now lives in West Sussex with his wife, Sue, who comes from Liverpool. They have three daughters, two sons and ten grandchildren.