Matthew Henry — a detailed look

To fully appreciate the life and ministry of Matthew Henry, we first need to consider his ancestry and background.

His grandfather was John Henry (1590-1652), the son of Henry Williams of Briton Ferry, which lies between Swansea and Neath in South Wales.

John Henry became a courtier under James I (1603-1625) and then Charles I (1625-1649). His son — Matthew’s father, Philip (1631-1696) — had as godparents the Earls of Pembroke and Carlisle and the Countess of Salisbury.

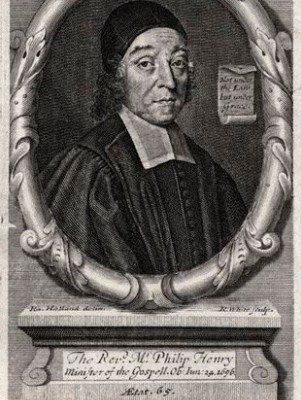

Philip Henry

As a child, Philip used to play at St James’s Palace with the younger Princes Charles and James, later to become Charles II and James II. It is no surprise then that Philip’s early lifestyle was also that of a courtier and that he retained his royalist allegiance.

The Civil War broke out when he was 11 years old and lasted on and off for the next nine years. Philip favoured the restoration of the monarchy with the return of his friend as Charles II (1660-1685).

At the age of 12 Philip attended Westminster School, becoming proficient in Greek and Latin. His mother took him to hear the preaching of the Westminster divines, including Stephen Marshall (1594/5-1655), under whom he was ‘begotten again unto a lively hope’, and Thomas Case (1598-1682).

He was also influenced by the ministry of William Bridge of Great Yarmouth (later, Norwich), the author of A lifting up for the downcast. In 1647, aged 16, Philip entered Christ Church, Oxford, graduating with a BA in 1651, the year Cromwell appointed John Owen as Dean of Christ Church. He proceeded to an MA in 1652.

Owen’s recommendation helped Philip become a tutor for Judge John Puleston’s sons, and Puleston later appointed him to Worthenbury Chapel, Iscoyd (now Bangor Is-y-coed), in 1654.

Following Philip’s induction in 1657 at Prees in Shropshire, Puleston formally gave him the living in 1659 and built him a new parsonage.

Nonconformity

Philip Henry’s views on church government were against episcopacy (government by bishops) and for the Presbyterian system (government by presbyters under a moderator). It was into that system that he and John Owen had been ordained. As for the Independents, Philip, in his diary, commended them for their church discipline, love and their correspondence with one another.

Although favouring the parish system, he had scruples about using the newly issued Book of Common Prayer (1662). He attended Anglican communion services, but refused to kneel at the altar rail, as he believed this contrary to the notion of a supper and more in keeping with the idolatrous practices of Roman Catholics.

Although Charles II was tolerant of differing modes of worship, his government was not, and trying times lay ahead for believers, particularly with the publishing of the Corporation Act (1661), which prevented Nonconformists from taking public office, and the Act of Uniformity (1662).

Under the Act of Uniformity over 2000 clergymen were expelled from their churches, in the Great Ejection of 1662, because they refused to take the oath not ‘to endeavour any change or alteration of government either in church or state’, and to declare their ‘unfeigned assent to all and everything contained in and prescribed in … the Book of Common Prayer’, which included the episcopal ordination of ministers.

Philip Henry was one of the ejected ministers and so left Worthenbury to take residence at the estate of his wife, Katherine (1629-1707), at Broad Oak and Bronington, Flintshire.

Their first son John (1661-1667) was born at Worthenbury, but Matthew and his four sisters were born at Broad Oak. Matthew was baptised at Whitewell, but Philip refused to assist, because he would not make the sign of the cross.

|

| Philip Henry |

Persecution

Hot on the heels of the above-mentioned Acts came the Conventicle Act (1664), which outlawed the meeting together for worship of more than five non-family members; and the Five Mile Act, which prevented ejected ministers from living within five miles of their previous parishes and from teaching in schools.

The king, aware of the harshness of these Acts (known as the Clarendon Code), issued a Declaration of Indulgence in 1672. Philip now exercised his preaching ministry from Broad Oak. This short interval of peace came to an end when Parliament forced the king to withdraw the Declaration in 1679.

Charles II died on 6 February 1685, and on 11 June the exiled Duke of Monmouth, Charles’ illegitimate son, landed at Lyme Regis in Dorset with a small force, in an attempt to topple the new Catholic king, James II.

At this time the authorities were very suspicious of meetings and possible plots, and Philip was arrested for defying the Conventicle Act and incarcerated in Chester Castle for three weeks.

By 1687, conditions for Nonconformists had improved, and Matthew Henry, who was now aged 24, was able to be ordained at Broad Oak on 9 May by his father and five other colleagues.

During the following year, all five of Matthew’s siblings were married at Whitewell Chapel. Then in 1689 the Act of Toleration was passed. This allowed Nonconformists their own places of worship and their own teachers if they accepted certain oaths of allegiance.

Philip died on 24 June 1696 and was buried at Whitchurch. Each of his four daughters was bequeathed a copy of Matthew Poole’s Annotations, while the rest of Philip’s library went to his wife and Matthew. Matthew preached one of his father’s funeral sermons.

Matthew Henry

Matthew Henry was born prematurely on 18 October 1662 at Broad Oak, Flintshire. He was a sickly child, but was intended for the ministry from an early age. He was educated at home, becoming proficient in languages and with a particular aptitude for Hebrew.

There is credible evidence that he could read portions of the Scriptures when he was only three years old. According to his own reckoning, his conversion took place before he turned eleven. It was one of his father’s sermons that, in Matthew’s words, ‘melted’ him and caused him to ‘inquire after Christ’.

His father had by this time become a well known preacher and, as early as 1658, took a month off to visit Oxford, preaching at St Mary the Virgin, Christ Church and Corpus Christi College. Philip also visited London, where he preached at Westminster Abbey. Matthew would have learned from him many of his pithy sayings, together with his Nonconformist principles.

From 1680, when Matthew was 18, he attended for three years the important Dissenting academy of the puritan Thomas Doolittle at Islington. Doolittle (1630-1707) was born at Kidderminster and converted at the age of 17 under the preaching of Richard Baxter.

The Dissenters faced a period of persecution in 1683, so Doolittle had to move his academy from Islington to Battersea, and Matthew returned home before proceeding in 1685 to study law at Gray’s Inn.

This legal training is evident in many forensic terms used throughout his exposition. He continued with his theological studies and attended the best preachers he could find.

Ordination and marriage

Matthew was ordained privately in May 1687 by six ejected ministers and preached his first public sermon at White Friars, Chester, on 2 June, in some converted stables.

|

| Chester today. |

In August 1700 the growing congregation moved to a purpose-built meeting house in Crook Lane. A gallery was added in 1707. (This building was pulled down in the 1960s to build the Forum Shopping Centre.)

‘We know’, recorded Henry in his diary, ‘how to enlarge the straitness of the place. God by his grace enlarge the straitness of our hearts’. They now numbered 350 communicants, with 300 in regular attendance.

Matthew married Katherine in 1687, but she died of smallpox at the age of 25, leaving a daughter, also named Katherine. He married Mary five months later. Together they had eight daughters and a son, Philip, who became MP for Chester.

Matthew preached in the villages around Chester and also made annual preaching tours to Lancashire and Staffordshire. He and his congregation were abused by High Churchmen, and an attempt was made to burn down their meeting place in 1692.

In a letter Matthew told his father that four pew doors, two on either side of the aisle (one being his wife’s seat), had been opened and the fire kindled beneath them.

As it was the middle of the night, it was a miracle the fire was discovered. ‘The light and roaring of it was more terrible than one could imagine’. God also overruled, in that Richard Lee, ‘tho’ an enemy to the Chapel’, was very helpful in quenching the fire because his hay loft adjoined it.

Matthew began his Exposition of the Old and New Testament with his comments on the Pentateuch in 1704. This part was published in folio three years later. He completed the entire Old Testament in 1712, during the period of Queen Anne (1665-1714), daughter of James II. Although Anne’s parents were Roman Catholic, she was brought up as a member of the Church of England and had a Protestant governess.

Several times in his Exposition Matthew gives thanks to God for a resulting period of national peace and freedom from persecution.

Thus on Esther 10:3 he comments: ‘Thanks be to God, such a government as this we are blessed with, which “seeks the welfare of our people, speaking peace to all their seed”. God continue it long, very long, and grant us, under the happy protection and influence of it, to “live quiet and peaceable lives, in godliness, honesty and charity”!’

The same year that he completed the Old Testament, on 18 May 1712, Matthew received a call to minister in Hackney and soon took his place among the leading ministers of his day.

A method for prayer

Matthew Henry published 30 other works, but only his Exposition, and now A method for prayer, have endured.

He referred to prayer as a ‘sweet and precious duty’. He said, ‘I love prayer. It is that which buckles on all the Christian’s armour’. Accordingly, he set about writing a manual on prayer which he entitled A method for prayer (1710).

In its preface he writes: ‘When I had finished the third volume of Expositions of the Bible … I was willing to take a little time from that work to this poor performance, in hopes it might be of some service to the generation of them that seek God’.

Matthew defines prayer thus: ‘Prayer is the solemn and religious offering of devout acknowledgments and desires to God, or a sincere representation of holy affections, with a design to give unto God the glory due unto his name thereby, and to obtain from him promised favours, and both thro’ the Mediator’.

He sets out to explain the various divisions of prayer — adoration, confession, petition, thanksgiving and intercession. Prayers for special occasions are given, but most interesting is chapter 8, ‘A paraphrase on the Lord’s Prayer, in Scripture expressions’.

He is aware that in giving examples of prayers, people might simply formally recite them, and so he comments: ‘A man may write straight, without having his paper ruled’.

Death and legacy

Matthew had just completed his commentary on the Gospels and Acts when he died, on 22 June 1714, at the home of Rev. Joseph Mottershead, near Nantwich, as a result of a fall from his horse while on a visit to Cheshire. So much studying and lack of exercise had made him corpulent.

The sorrow at his death was universal: ‘There was hardly a pulpit of the Dissenters in London but what gave notice of the great breach that was made upon the church of God’.

He was buried on 25 June in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church, Chester, and the funeral was attended by eight of the city clergy. After his death, 13 Nonconformist ministers of varying abilities completed his New Testament exposition, referring to Matthew Henry’s notes.

Undoubtedly, Matthew Henry’s Exposition is a treasure bequeathed to Christ’s church on earth. C. H. Spurgeon stated: ‘First among the mighty for general usefulness we are bound to mention the man whose name is a household word, MATTHEW HENRY.

‘He is most pious and pithy, sound and sensible, suggestive and sober, terse and trustworthy … he is deeply spiritual, heavenly, and profitable; finding good matter in every text, and from all deducing most practical and judicious lessons … It is the poor man’s commentary, the old Christian’s companion, suitable to everybody, instructive to all’.

Exposition

Matthew Henry’s Exposition was written about 100 years after Shakespeare’s plays, so the English is not as obscure as it is in those works, and one is not aware of it being too dated in modes of expression.

Baptists make allowances for the occasions he underlines his paedobaptist views, but these are few and far between. Today, there are many more modern commentaries to choose from, but Matthew Henry’s has stood the test of time.

One of the most repeated and choicest quotations from it is on Genesis 2:21-23: ‘Observe: That the woman was “made of a rib out of the side of Adam”; not made out of his head to rule over him, nor out of his feet to be trampled upon by him, but out of his side to be equal with him, under his arm to be protected, and near his heart to be beloved’.

There are striking notes for every occasion, such as the following examples from Genesis and Revelation. Concerning the death of a young believer he writes: ‘God often takes those soonest whom he loves best, and the time they lose on earth is gained in heaven, to their unspeakable advantage.

‘Those whose conversation in the world is truly holy shall find their removal out of it truly happy’ (Genesis 5:23-24). A comment applicable to suicide or euthanasia is: ‘Our lives are not so our own as that we may quit them at our own pleasure, but they are God’s, and we must resign them at his pleasure; if we in any way hasten our own deaths, we are accountable to God for it’ (Genesis 9:5).

Gems

Concerning old age, he says, ‘Old age is a blessing. It is promised in the fifth commandment; it is pleasing to nature; and it affords a great opportunity for usefulness’ (Genesis 15:15).

Regarding prayer Henry says, ‘All the saints are a praying people; none of the children of God are born dumb, a Spirit of grace is always a Spirit of adoption and supplication, teaching us to cry, “Abba, Father”’ (Rev. 8:3).

As for God’s wrath, ‘When the sins of a people reach up to heaven, the wrath of God will reach down to the earth’ (Revelation 18:5).

The final quote in this book exhorts us to seek the grace of Christ while we have opportunity, and points us to glory: ‘Nothing should be more desired by us than that the grace of Christ may be with us in this world, to prepare us for the glory of Christ in the other world’ (Revelation 22:21).

There are hundreds more gems, some rather quaint, but all profitable. With single-volume unabridged editions for under £30, and free online versions, this great work is now within everyone’s reach.

Nigel Faithfull

Bibliography:

Richard Bonney and D. J. B. Trim (eds.), Persecution and pluralism: Calvinists and religious minorities in early Modern Europe 1550-1700 (Peter Lang, 2006).

Matthew Henry, A catalogue of mercies.

Matthew Henry, A method for prayer.

Charles H. Spurgeon, Commenting and commentaries: lectures addressed to the students of the Pastor’s College, Metropolitan Tabernacle.

William Tong, An account of the life and death of Mr Matthew Henry, minister of the gospel at Hackney, who dy’d June 22, 1714 in the 52d year of his age (W. Baynes, 1716).

J. B. Williams (ed.), The lives of Philip and Matthew Henry (Banner of Truth, 1974).

John Bickerton Williams, Memoirs of the life, character, and writings of the Rev. Matthew Henry (Joseph Ogle Robinson, 1829).

Click here for other Articles concerning Matthew Henry

Matthew Henry also appears on the ET Timeline.