Isaiah 19 predicts that one day the worship of the true God will be supreme in Egypt. In Acts 2, Egyptians were among the many converts on the Day of Pentecost. Tradition has it that the evangelist Mark, perhaps along with these Egyptian converts, spent much time preaching in Egypt. Whether or not this was the case, the Christian faith spread there rapidly.

As the early church grew, it found a people in Egypt that already had the Old Testament Scriptures in Greek, a language widely spoken in the northern part of the Nile delta. In the following centuries Egyptian Christians played a highly influential role in the early church. Alexandria, with its great library, was an important centre, while leading Egyptian church leaders and thinkers included Clement, Origen and Cyril.

Heresy and division

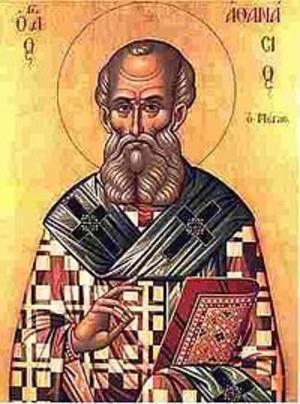

Athanasius of Alexandria (AD 296-372) contended valiantly for the fundamental truth of Christ’s deity. Athanasius stood against Arius, an articulate and influential North African presbyter who denied Christ’s eternal deity. Many prominent church leaders embraced Arius’ teaching and this heresy is still propagated by deviant Christian sects today.

By the turn of the sixth century, the struggle for supremacy between Byzantine, Roman and Alexandrian church leaders was a sad reflection of the early medieval church’s aspirations after earthly power and riches rather than the kingdom of God. The once universal church became divided into the western, Roman Catholic and the eastern, Byzantine (Orthodox) churches.

The eastern church, in turn, was further divided. Some followed the Council of Chalcedon’s teaching, which declared that Christ enjoyed distinct divine and human natures. Others embraced the heterodoxy of the Monophysites, who claimed that Christ had only a single, divine nature, albeit clad with his human nature. The Egyptian churches embraced the latter error, rejecting Chalcedon and separating from the Byzantine churches.

Gradually all churches, eastern and western, lost their focus on the Bible and the gospel. The biblical tradition of Athanasius gave way to liturgy, formalism and superstition. Those who were true Christians found themselves isolated and persecuted by both Roman and Byzantine churches.

Growing Islamic influence

When the Muslim armies reached Egypt’s borders, in the middle of the seventh century, they were received warmly by Egyptian church leaders, who viewed them as potential allies against both Rome and Constantinople! It is thus no surprise to find that many Egyptian ‘Christians’ converted to Islam for social advantage.

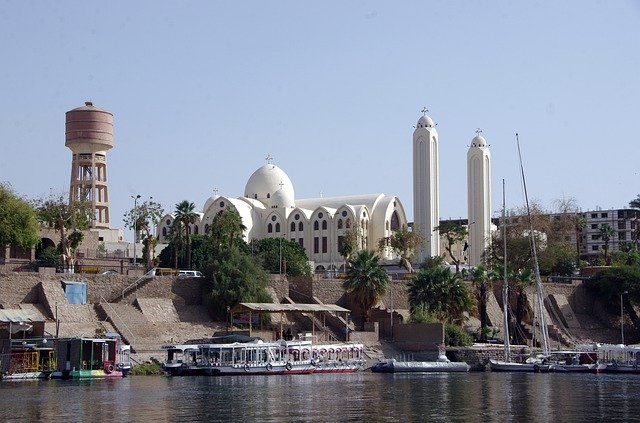

These conversions did not disturb the peaceful coexistence that was established between a wealthy church hierarchy and the ruling Arabs. For more than three centuries, Muslims governing Egypt dealt kindly with their Coptic hosts (Coptic means ‘Egyptian’).

It was only at the turn of the eleventh century that the Muslim caliph, Al-Hakim, determined that Islam should become the uncontested religion of Egypt. He imposed the Arabic language on the whole population and introduced restrictive laws and taxes on Christians.

Much of the church in northern Egypt was rich enough to pay these taxes, but those who could not pay (and would not convert to Islam) moved southward up the Nile River and settled in Upper Egypt. Gradually the populous north became Muslim.

Defensive

The Coptic Church became inward-looking and defensive, concentrating its efforts on preserving Coptic as its ethnic and religious language. This was a terrible mistake. The Coptic language could not keep up with the vibrant Arabic language. For several centuries Arabic was the language of philosophical and scientific learning throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and eastern and southern Europe.

Instead of teaching people the Bible in a language they could understand, the Coptic Church conducted worship in Coptic. Knowledge of the Scriptures was limited to monks and priests who knew this language.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the number of professing Christians throughout Lower and Upper Egypt had shrunk to less than 40% of the total population. Today it is estimated at less than 18%.

Reformed missions

European Protestant missionary work in Egypt began in the seventeenth century with German Moravian and Lutheran missions. The Anglicans commenced working in Egypt in the early nineteenth century. Not until the middle of the nineteenth century did evangelical missionary efforts begin to bear lasting fruit.

The key to their success was the work of Reformed missionaries, from North America and Europe, in translating the Scriptures into Arabic. Eli Smith and Cornelius van Dyke, together with Christian Arabic-language scholars like Naseef Yaziji and Butros Bustani, persevered to accomplish this strategic task.

The American printing press in Beirut made the Word of God available to millions of Arabic-speaking people. The Egyptian Coptic Church quickly endorsed the distribution of the Arabic Bible as a means of keeping hold of its own people.

Largest Reformed community

During the second half of the nineteenth century the Lord used the efforts of dedicated Reformed missionaries to disciple tens of thousands of Coptic people and scores of former Muslims. This led to the establishment of vibrant Reformed congregations throughout Egypt.

Quickly, the missionaries realised that they must train local pastors, evangelists and church officers. Training an indigenous leadership for the churches proved prudent and effective for future growth. Today, the Egyptian Reformed community is the largest Bible-believing community in the Mediterranean region.