From 200 B.C. until A.D. 1200 this area was ruled variously by Buddhist or Hindu dynasties. Muslim domination came when the Delhi Sultanate was established in 1206. After that, Afghan and then Mogul rulers governed the territory for 600 years. During the time of the Moguls, different European traders began to visit Bengal. Eventually, in 1857, Bengal became part of British India.

During the early twentieth century new links were forged between Bengali Muslims and their Arab co-religionists. One result of this was the emergence of de facto Muslim castes, which added further complications to a society already influenced by the Hindu caste system. Muslim caste meant that the ‘Sharifs’ of Arabic origin were perceived as being highly superior to the ‘Banglas’ of local origin. This perception had the effect of causing Bengali Muslims to opt for a Middle-Eastern rather than a local identity and so elect to be incorporated into Pakistan in the Partition of 1947. Thus East Bengal became Pakistan’s eastern province (known from 1955 as East Pakistan), while West Bengal continued within India.

Yet there were differences in outlook between East and West, which political union could not eradicate. These reasserted themselves over the next twenty-four years as resentment grew in the East over West Pakistan’s political and military dominance. This resentment was fanned by the latter’s apparent indifference to the catastrophic floods of 1970. In 1971 elections were won by the Awami League, who had openly campaigned for Bengali autonomy, and East Pakistan proceeded to secede from West Pakistan. A catastrophic nine-month civil war ensued, which resulted in an estimated one million Bengali deaths. In the end military help from India proved decisive in helping the East to break away and form the state of Bangladesh in 1972.

In 1975 Sheik Rahman, the first prime minister, was assassinated in a military coup. Further coups followed and Lt-Gen Ershad seized power in 1982. Under Ershad the economy improved and elections were held. During 1987 the Awami League, now in opposition, campaigned against the government, with violent strikes and demonstrations, and Ershad proclaimed a state of emergency. Fresh elections followed, but, after an opposition boycott and alleged ballot-rigging, these resulted in Ershad’s ruling party being returned to power.

Martial law was lifted in April 1988 and during this same year Bangladesh officially adopted an Islamic constitution. In 1990 Ershad resigned. Elections in September 1991 secured an absolute parliamentary majority for the Islamic-orientated Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Begum Zia became the first woman prime minister. However, stability still did not emerge; from March 1994 the Awami League boycotted parliament and organized street protests.

Difficulties

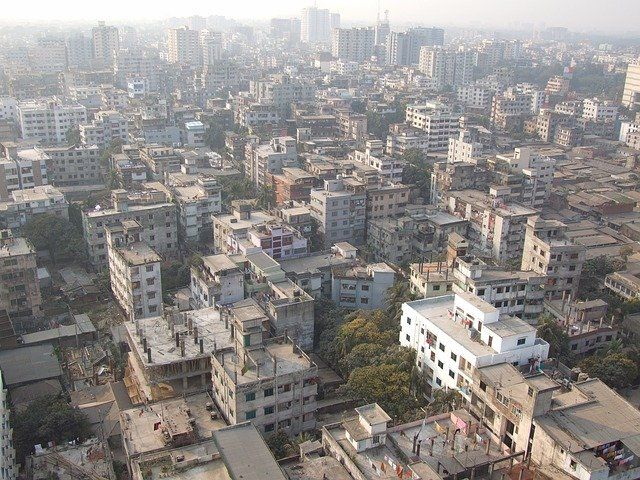

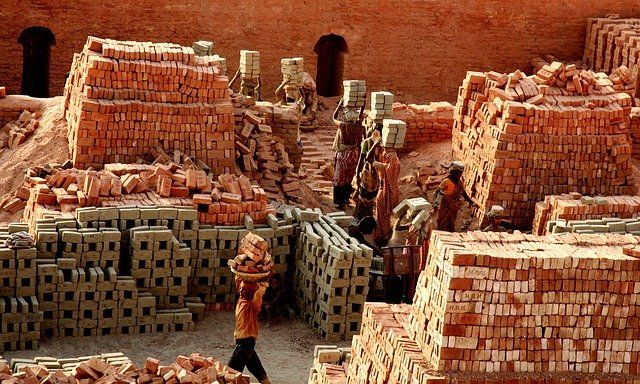

Throughout the modern state’s history it has struggled with enormous difficulties. It has been dogged by poverty, caste, corruption, conflict between Bengalis and tribals, and military coups. Natural disasters have exacerbated all these problems. Millions of refugees, initially due to the 1971 civil war, have fled into India and this, in turn, has led to tensions between these two countries. In 1992 sixty thousand Muslim refugees fled into Bangladesh from Myanmar, causing further depletion of the country’s scarce resources. Hundreds of thousands were killed by the famine of 1974; 1988 saw severe monsoon floods which killed thousands and left 30 million homeless; in 1991 a further devastating cyclone killed 139,000 and made 10 million homeless.

Church history

Portuguese Roman Catholicism came to the area during the seventeenth century. Protestant missionary work began with William Carey’s arrival in Calcutta in 1793 and Baptist work soon spread into East Bengal. Carey himself preached in Dinajpur district between 1794 and 1800. Baptist churches were planted at Jessore and Khulna in 1812 and at Barisal in 1829. Vigorous Baptist preaching led to the establishing of churches in the Bakerganj and Faridpur districts between the 1850s and 1870s. The Church Missionary Society began work in Kushtia district in 1821.

Other denominational and interdenominational missions followed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These saw some accessions to the churches, particularly in the districts of Mymensingh, Tangail and Chittagong Hill Tracts. Many of the ‘conversions’ were in reality ‘people movements’; that is, lower-caste, animistic Hindus embraced ‘Christianity’ as a new system that promised shelter from oppressive landlords and the impact of the harsh physical environment. Growth of the churches between 1900 and 1970 was in reality very slow, and few new churches were planted.

Reaching Muslims

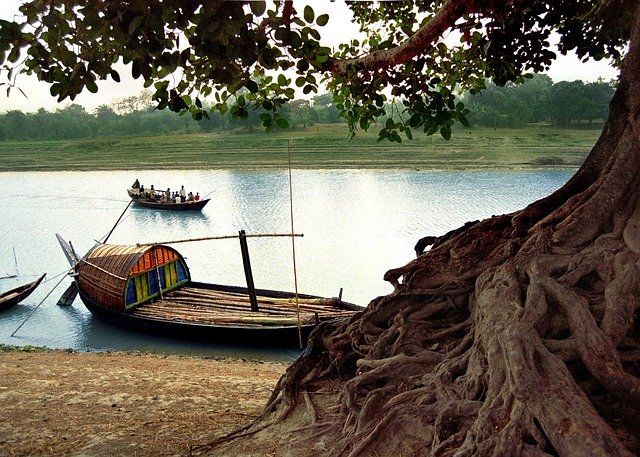

By 1975 there were 83,000 professing Protestant Christians, mainly from a Hindu or animistic background. Missionary work still concentrated on large cities like Dacca, Khulna and Chittagong, with minimal impact on the majority rural Muslim community. This disparity caused some evangelical missionaries, during the early 1970s, to explore new ways of reaching Muslims. A new translation of the New Testament was produced in a Muslim dialect (the Old Testament has yet to be completed). Carey’s Bengali version of the Bible, still used by the oldest Christian churches, is said to employ an idiom intelligible only to Hindus; the new translation addresses Muslims in their own idiom. These initiatives have reportedly included the adoption of some culturally ‘Islamic’ (and allegedly harmless) practices in relation to Christian worship. There has been a corresponding growth in the number of village congregations or house-groups.

Not all indigenous Christians have agreed with these experiments. The Hindu background of the Church in Bangladesh may have something to do with this, but concern is justified if biblical principles have been sacrificed to the goal of ‘church growth’. There is an immense difference between legitimate cultural sensitivity in evangelism, and unbiblical ‘contextualization’ of gospel or worship, even when inspired by genuine evangelistic motives. Both the gospel and true worship are supra-cultural. All this is not to deny that sincere and intelligent attempts have been made to communicate the gospel to Muslims. However, the long-term implications for biblical Christianity have yet to be fully assessed.

In the recent past, missionaries have been obliged to work with the government in bringing material relief during national disasters. This happened, for example, in the aftermath of the civil war of 1971. A more recent example is that, during the early 1990s, missionaries were required by the government to undertake ‘development work’ – agriculture, medicine and the like – rather than direct ‘missionary work’. Generally speaking, the involvement of churches per se in relief programmes can lead to local misunderstandings, as it did in the early church (see Acts 6). It also encourages the phenomenon of ‘rice Christians’.

Priorities

1. While indifference to the poverty and distress facing Bengalis would be wrong, there is always a danger that the endemic poverty will distract Christians from preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The central task of mission is to preach the gospel, rather than to address social needs. Only the righteousness of Christ can cover people’s spiritual nakedness and save them from an eternity in hell. Only trust in a sovereign and loving God, who controls all things for the good of his people, will enable men to face material poverty and disaster with true peace of heart. Gospel priorities remain paramount for the church in Bangladesh today, as they do for Christians everywhere.

2. There is scope for expressing Christian unity more effectively, in particular between converted Muslims and converted Hindus. Today there are said to be ‘two churches’ in Bangladesh, one drawn from the Muslim community and one from the Hindu. The first-century church had to learn that Jewish and Gentile believers must receive each other for Christ’s sake (Romans 14). The churches of Bangladesh need to learn the same lesson.

This should not be impossible. It was said of the Baptist Church in Jessore in the early 1800s: ‘The converts did not come from any sect or caste. They included both Hindus and Moslems, and among the Hindus there were individuals from many different castes including Brahmin. This was a true gathered community.’

3. Believers in Bangladesh face harsh physical and spiritual environments. They live in the shadow of a militant Islam, although their numbers are slowly increasing. Yet there are very few preachers in Bangladesh who teach the doctrines of grace, and only a few sovereign-grace Bible commentaries have yet been translated into Bengali. There is a paramount need to establish believers in the grace of God, through preaching and literature which teach clearly the faith once delivered to the saints.