Mongolia experienced colossal political changes between 1990 and 1993.

The 1990 elections initiated two years of democratic reform. The Soviets left, the constitution was rewritten, and there was talk of Mongolia becoming another Asian economic tiger. Democracy and market reform had come to stay.

From a missionary perspective, Mongolia was then a clean slate. She had no recent history of missions, no western colonial history, no established church.

So this period was characterised by a flurry of evangelistic activity aimed at a new generation of Mongolian youth, who had witnessed the collapse of Communism, and for whom the Tibetan-Buddhism of their parents, and the Shamanism of their grandparents, were irrelevant. Here was a spiritual void waiting to be filled.

The first years of church growth took place mainly among these young people, and often among girls.

Nevertheless, by the mid-1990s, young men and older people were entering the churches.

Discrimination

In December 1993 a new law was proposed redefining the relationship between Religion and the State.

Christians argued against this new code, claiming that it discriminated against Christianity, since it named Tibetan-Buddhism, Shamanism and Islam (a concession to the Khazak minority) as the official state religions. It also implied that to be a genuine Mongolian was to be a Buddhist.

Eventually a revised version of the law was passed, allowing public religious acts including Christian preaching, but insisting that all places of religious worship must be registered with the State. The State would also control the number of clergy officiating in any religion.

The most immediate problem for Christian churches was to find alternative meeting places.

But in spite of such problems, it has been God’s sovereign time for Mongolia to enter into new freedoms and opportunities. It is estimated that there are around 12,000 Protestants in Mongolia today. We can only stand back and watch God work.

Challenges

The emergent Mongolian church has major challenges to face.

Two contemporary translations of the New Testament are extant which vary in their degree of dynamic equivalence and contextualisation. This has created tensions.

Mongolia is a clean missiological slate, and it has been tempting for western missionaries to ‘do their own thing’. Some have! There have been church splits and major misunderstandings.

However, at a grass-roots level, there has been informal co-operation, vision sharing, and praying together.

There has been co-operation between churches and the government too. Christian agencies provide English teachers, veterinarians, teacher training, agriculturalists, doctors and others.

As a result, Christianity is in good standing with the government, and believers have been able to witness to the love of Christ by providing vital services for the nation.

Church planting

Church planting has been a healthy preoccupation. Even though foreign Christians have made genuine efforts to learn the language, the Mongolians themselves are best at reaching their own people.

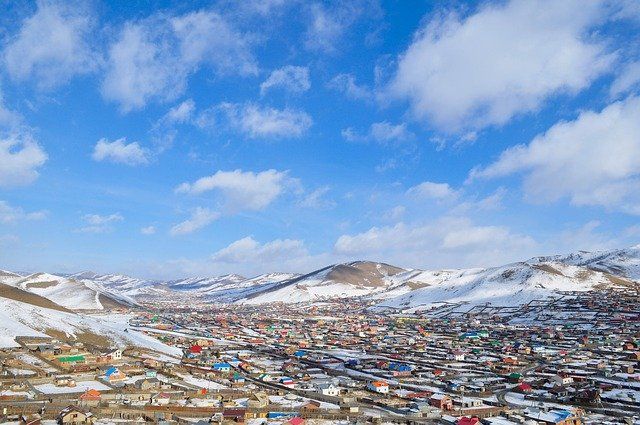

Some churches have prayed, evangelised, and established house groups in stairwells, buildings, housing estates, and suburbs. One Ulaanbaatar church had planted 19 daughter churches before it was six years old!

From the start, missionaries have emphasised the priority of the Great Commission. Many Mongolian churches are aware of their responsibility in this matter. Evangelistic teams have gone to Buriatia (Russia) and Hoh-hot (Inner Mongolian China).

Within Mongolia itself, Mongols are evangelising Khazaks, Chinese and the residual Russian population.

Although Mongolians are being trained as pastors, there is still a role for foreign Christians, especially behind the scenes.

Speakers of the Altaic languages (Korean, Hungarian, Finnish) have a unique opportunity to contribute significantly, as they can learn Mongolian (a related language) more quickly.

Korean influence

Koreans were influential during this first decade in Mongolia. Their clear and uncompromising presentation of saving grace in Christ, along with their personal disciplines of perseverance, prayer, Bible study and evangelism, were a driving force behind much of the early church growth.

But now it is the Mongolian church that has a unique opportunity to influence the formation of the modern Mongolian nation.

Mongolia is ‘opening the books’ on her past 70 years under Communism. Atrocities, missing persons, purges and mismanagement are tentatively being addressed. If Christians can lead the nation in genuine reconciliation, rooted in the gospel, then suspicion and fear will be replaced by integrity, justice and kindness.

Militant Buddhism

But the church should not underestimate the spiritual struggles ahead, especially those arising from militant Buddhism.

There is a renaissance of Tibetan-Buddhism. Idols are being rebuilt, novices recruited, Lamas are writing in the newspapers and again beginning to dictate the rhythms of family and national life.

The Mongolian church needs to equip itself with the truth to meet all such challenges, and to continue to live out graciously the gospel of Christ.