Features

Third largest land-mass in the world: 3.5 million sq. miles.

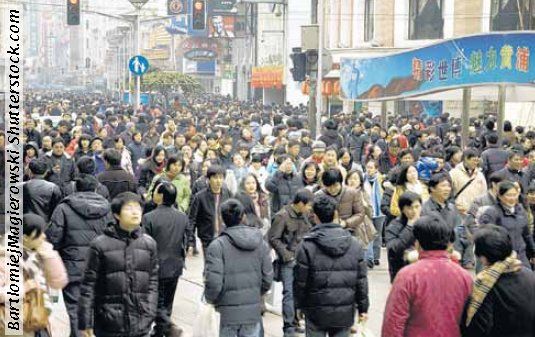

Highest population in the world: 1.2 billion. 67 million belong to ethnic minorities in border areas like Tibet and Inner Mongolia.

Bounded by Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, India, Nepal, Myanmar, Vietnam, North Korea, Russia.

Very high plateaux and mountains, as well as desert.

Frequent natural disasters, including earthquakes and flooding.

Cities: Beijing (capital) – 10.8 million; Shanghai – 13.3 million. 40 cities with over 1 million people.

Hong Kong will revert back to China in July 1997. Macao is due to be returned to China by Portugal in 1999. China also (unsuccessfully) lays claim to Taiwan.

Exports:tea, cereals, livestock products, silk, cotton, oil, minerals, light-industrial goods and toys.

Religions: Chinese religions (Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, animism); Islam; Roman Catholicism. Most of today’s population have known only Communism.

History

Many ancient dynasties have ruled China from the earliest times. By 1644 the Mongols had been expelled and up to 1912 the country was ruled by its last great dynasty, the Manchu. During the nineteenth century China was commercially dominated by the West with all trade being conducted through the treaty ports. China felt humiliated by this and by its defeat in the opium wars. This gave rise to the Boxer Rebellion against Western influence in 1900.In 1912 it became a republic but was soon divided among its feuding warlords.

The Chinese Communist Party was to be the force which eventually unified the country in 1949 under Mao Tse Tung. From 1958 there issued the ‘Great Leap Forward’ of Chairman Mao, a massive attempt to apply Marxist dogma to industry and agriculture. This was a disaster and led to widespread economic failure. Over 20 million died in the floods and famines of 1959 -1960. As a result Mao’s influence was reduced.

Mao hit back with his ‘Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution’, lasting from 1966 to 1969. The Cultural Revolution saw Red Guard demonstrations against anyone suspected of rightist views. Social and industrial anarchy resulted, with great suffering. Political opponents and intellectuals were severely persecuted. It is estimated that 20 million Chinese lost their lives during this time. Irreconcilable quarrels between China and the USSR also surfaced.

By 1970 Mao had become more moderate. This led him to side with the more pragmatic Chou en Lai to restore stability. China also began to soften its international posture. When both Mao and Chou died in 1976, a struggle for power ensued between radical leftists, led by the ‘Gang of Four’, including Mao’s widow, and moderate rightists, grouped around Deng Xiaoping. The ‘Gang of Four’ were subsequently discredited.

From 1976 the more pragmatic leadership of Deng resulted in new economic growth and political relaxation. He sought to build better relationships with the West with an eye to increasing material prosperity at home. Towards the end of the 1980s Deng’s economic miracle began to run out of steam. The gap between rich and poor had widened and there was deepening inflation. Increased exposure of ordinary people to Western ideas had begun to fuel demands for democratic change. Urban unrest and the spread of student-led pro-democracy demonstrations climaxed in May 1989 with a mass demonstration in Tiananmen Square, Beijing. This protest was crushed with tanks and over 2,000 protesters were killed. There followed widespread repression. The 1990s have seen Western sanctions over Tiananmen being eased but since the death of Deng in February 1997 a belligerent nationalism has re-emerged, fuelled by the prospect of Hong Kong returning to the fold.

There are deep social problems in China with a breakdown in family life, widespread abortion and divorce as well as violence and suicide. 65 million people still live below the poverty line and over 100 million are unemployed. The cities have been flooded by a ‘floating’ population of tens of millions, many of whom have turned to drugs and crime. Jiang Zemin, Deng’s successor, has countered these trends with an ‘anti-crime’ campaign.

The church

Robert Morrison was the first Protestant missionary to China in 1807. He faced intense hostility there yet he succeeded in translating the Bible into Chinese. William C. Burns from Scotland followed in 1847 and saw blessing in Fukien province. James Hudson Taylor arrived in 1853. Missionary work continued right into the mid-twentieth century although both Chinese and foreign Christians were attacked in the brief Boxer Rebellion.

When China became entirely Communist from 1949 missionaries withdrew. It was required of the Protestant churches that they register with a government organization called the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM). In the 1950s many Christians refused to compromise in this way. Their churches were closed and leaders thrown into prison. Vicious persecution followed during the Cultural Revolution. This gave fresh impetus to an underground house-church movement.

From 1978, under Deng, there was a change in the fortunes of the church. All over China Mao’s statues and portraits were removed. Deng rehabilitated many Christians and church buildings were reopened. There was greater freedom for evangelism. A dramatic increase in numbers attending all the churches resulted. It is claimed that in the twenty years since Mao’s death these have increased twentyfold.

According to recent official figures 12,000 churches have been opened between 1979 and 1997, and there are at least 25,000 registered house churches, not to mention the many which remain unregistered. One China watcher reported to ET in glowing terms, ‘It is my considered view that the work of God in China over the last twenty-five years since the end of the Cultural Revolution is one of the greatest manifestations of his sovereign grace in the entire history of the church. Between 1966 and 1979 the visible church had been totally eradicated by Mao. Yet today there are probably very conservatively 25 million evangelical Protestants compared to around one million in 1949. Even the government admits to eleven million. I first lived in China in 1973 – there were no churches and no sign of any Christian witness whatsoever. Yet today Wenzhou in Zhenjiang Province alone has 600,000 Protestants out of 6 million inhabitants (government statistics), i.e. 10% of the population … One Shanghai house-church friend helped baptize 1,100 people at a nine-hour service in August 1995 … and I have personally witnessed 250 people being baptized by immersion in the old China Inland Mission church at Lanzhou at one Sunday service.’

However, careful evaluation is needed to assess what lies behind such reports. Enquiries conducted recently by Evangelical Times indicate that the present spiritual condition of the churches is very confused. While some may have a reverent approach to worship, preaching and prayer, false teachings are rife among professing believers and their spiritual climate is shallow. The late Watchman Nee’s house-church movement (‘Little Flock’), for example, blends together a mixture of mysticism and pietistic legalism.

There has been a flood of charismatic literature and the arrival of the Toronto Blessing from the West into an already charismatic scene. Long-standing groups with names such as ‘Audible Voice’, ‘Queen of the South’, ‘Salvation through Knowledge’ and ‘Shouters’ suggest continued exotic errors. There are few theologically mature leaders and few opportunities for sound and thorough theological training. The need for consistent teaching in the doctrines of grace and the dissemination of good Christian literature remains paramount.

Other reports paint a picture of corruption seeping into the churches through materialism and secularism. Chinese students are said to be fascinated with anything Western including its religion and material prosperity. In this respect China is probably a mirror image of what has happened, and still is happening, in many countries of Eastern Europe and also in the Third World. Churches are full and increasing in number, but their great spiritual shallowness is evident to the discerning observer. There is a craze for Western ‘values’ and it is likely that many people have flooded into churches in China in a quest for a health and wealth Utopia rather than for salvation through Christ alone.

There are external problems too. Although there is ‘freedom’ to practise religion according to the Chinese constitution,the Communist Party works on towards the goal of a ‘scientific’, atheistic society. Evangelism of young people under the age of eighteen years (who represent nearly half the population) is forbidden. Thus the present ‘anti-crime’ drive has become a fresh excuse for persecuting the Christian church. The government is nervous of the numerous house-church movements. Over one hundred house-church leaders were arrested and jailed between January and March of 1997 and there have been reports of fines, confiscations and beatings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ET enquiries suggest that there is a large professing church in China, still vulnerable to persecution, which has recently experienced a large increase in numbers. There are many errors and heresies, little Reformed literature and relatively little doctrinal grounding. Bibles are available even though local shortages have been reported.

Most Christians live in the south-eastern and central parts, but the north and west with their ethnic border regions remain less touched. There is a uniform need to instruct the teeming millions of Chinese children in the basics of the Christian faith. The middle-aged generation that grew up with the violent dislocation of the Cultural Revolution and its now exploded philosophies remains a generation lost to nearly any Christian influence at all, while the rest of the nation is little better off spiritually.