Jesus summoned his disciples to reach every nation with the gospel. Yet, down the centuries, while some areas have been open to that gospel, others have remained closed. Thus Belgium, Quebec and Ireland have all remained firmly wedded to the traditions of Rome. This does not excuse us from reaching these places, but it does commit us to try to understand why such communities stubbornly resist the ‘evangel’.

Early history

Christian history in Ireland began with Patrick in the fifth century. Captured in Britain by Irish pirates and deported to Ireland, he came to trust in his parents’ Saviour while in slavery. Escaping from his captors, he could not escape the insistent call of God to return to Ireland to preach the gospel there. The fruitful outcome was a widespread missionary zeal that took Columba to Iona and many others into Europe. The evangelising of England did not issue, as many think, from the pope sending Augustine to England from Rome, but from the arrival of Celtic missionaries from Lindisfarne.

In A.D. 664 the Synod of Whitby adopted the usages of the Roman Church. This led to the ebb of Celtic witness in England. Back in Ireland, Celtic Christians had to withstand the ravages of the Vikings. The Vikings, like many other invaders, gradually settled down and added their influence to the existing Irish population.

Then came invasion from England. This was not so much an English invasion as an Anglo-Norman one. What William the Conqueror did to England after defeating Saxon King Harold in 1066, Henry II tried to repeat in Ireland, and invaded it in A.D. 1171. Very conveniently for Henry, there was at that time an English pope – Adrian IV (Nicholas Breakspear). Indeed it was the only time an Englishman has ruled in the Vatican. Having got the pope’s approval well in advance, Henry supported the Romanising party in imposing the prayer book of Canterbury on the Irish Church.

Ulster Plantation

Henry II’s conquest of Ireland never succeeded in reaching across the country. It ended up as an occupied strip of land on the east coast, known as ‘the pale’ (hence ‘beyond the pale’ means being an outsider). This remained the position for four centuries, until Henry VIII declared himself king of Ireland. The ensuing warfare only ended at the death of Elizabeth I. She did succeed in increasing English dominance in Ireland.

Now James I conceived his master plan of establishing a permanent enclave in Ireland, colonised with people from Northumbria and Westmoreland, turbulent English counties where the king’s writ scarcely ran. Irish natives were expelled from their fertile farms, to give way to the newcomers. They were pushed into the mountainous regions of South Armagh, Tyrone and Fermanagh. The ‘Plantation of Ulster’, as it came to be called, occupied the rich farmlands of Counties Down and Armagh. The planters (including my forebears) established a new English population, which felt itself to be very English.

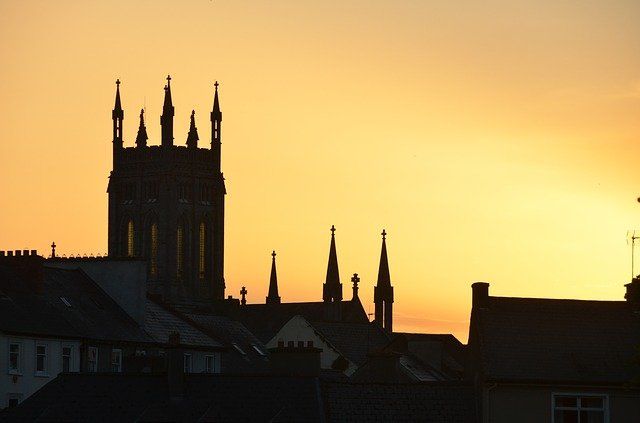

Like many such political bright-ideas, the Plantation had its ‘ragged edges’. Alongside the English planters there grew a large Scottish population, which settled especially in Antrim and County Derry. The Scots were almost certainly not sponsored by James, who had little time for Scottish Presbyterianism. The small town of Downpatrick, where I went to school, illustrates the fragmentation. It had three main streets: ‘English Street’, with big houses, leading to the Law Court, the Mall and the Cathedral; ‘Scotch Street’, with not so pretentious a pattern; and ‘Irish Street’, which originally led to the abattoir!

The seething indignation of the native Celtic population erupted in the massacre of many of the colonists in 1641. The savage response of the English reached its bloody climax under Oliver Cromwell. Drogheda’s population was slaughtered, and Limerick and Wexford’s brutally treated. Cromwell rewarded some of his generals with rich farming areas. When asked where the dispossessed Irish would go, he replied ‘To Hell or Connaught’.

Continuing divisions

Sadly, the sixteenth-century Reformation failed to give Ireland the Bible translated into its native Gaelic. Penal laws grossly discriminated against Roman Catholics. Thus language, culture and national identity alienated the majority of the original population from the Protestant ‘invaders’, even though it was the latter who possessed the gospel. Today, these ancient historical divisions are reflected in the religious labels in Ireland – ‘Roman Catholic’, ‘Protestant’ (meaning the Anglican, Church of Ireland) and ‘Presbyterian’ (meaning Presbyterians or Dissenters).

The situation is made worse by the competing references from different communities to ‘Mary, Queen of the Gaels’ and ‘For God and Ulster’. The latter slogan implies that God is on the side of partition, an assumption reflected in Northern Ireland when it established its own parliament in 1922, with the claim that it was ‘a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’. Thus the call to believe the gospel has been viewed by the southern Irish as an attempt to induce them to leave their politics and culture, as well as their religion.

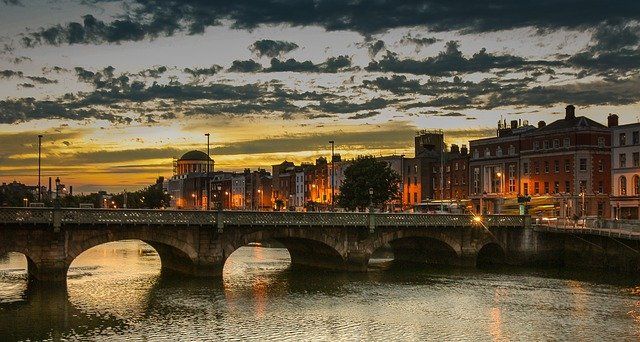

When I went up to university (Trinity College, Dublin) in 1940, religious boundaries were firmly set. College Chapel used the English Book of Common Prayer. There was no likelihood of an influx of Roman Catholic students into the chapel. After all, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin issued annually in his Lenten letter a warning against Catholic parents sending their children to any such institution that might corrupt their faith and morals. The same archbishop was known in the local patois as John Charles, and enjoyed a close relationship with the Prime Minister of the day, De Valera.

Open-air preaching

I look back to the days of my first curacy, in Belfast – in a parish abutting on the Falls Road. The area was a Catholic and nationalist stronghold, but they were years of peace. We were a strongly evangelistic church with open-air gospel preaching but, to our shame, we scarcely expected converts from Rome.

There were, however, different voices raised. A notable open-air preacher in the south was Johnny Cochrane. A Dublin accent and a gift of repartee added spice to his gospel preaching. This he undertook often in the face of hostile reaction, especially in the markets. One belligerent threatened him: ‘I’ll smash your teeth in!’ Johnny’s response was immediate: ‘You’ll do no such thing. I’ll take them out and put them in my pocket!’

T. C. Hammond, who was a redoubtable theologian, recalled at a student conference that he had been run out of Tipperary for open-air preaching. But there was greater freedom to evangelise in Dublin.

Gradually God’s servants began to experience a time of reaping. The evangelical churches began to expect great things from God. Brethren assemblies made a valuable contribution with their ‘Sunday school by post’. A famous CSSM (beach mission) each August in Greystone, began to attract Roman Catholic children, as well as the usual ‘Protestants and Dissenters’! A team of Baptist pastors went out preaching in cattle markets and fairs. One outstanding contributor to such preaching was a Lancastrian from Blackpool Tabernacle called Roy Shaw. He remained during the lean years encouraging a little evangelical church in Cork to hold fast.

New stirrings

In the providence of God I was called to Ireland in 1970 when, after fourteen years in London and then Cambridge, I was unexpectedly called to the pastorate of Hamilton Road Baptist Church, in the north, in Bangor, Co. Down. Although primarily the pastor of that local church, I became much involved in the ‘awakening’ down south.

A student was a key figure in the new situation that developed. He was Wallace Benn (recently made Bishop of Lewes). The usual pattern for Anglicans preparing for the ministry was to do the degree course in Trinity. He, however, had decided to go to an overwhelmingly Roman Catholic university in Dublin. As a student he could do there what an outsider could not. So it was quite a surprise when he contacted me to see if I would participate with a prominent Jesuit in a debate – I think the title was ‘What is a Christian?’

It was a crowded meeting, with a follow-up coffee meeting next morning. It made such an impact that further debates took place: with a Dominican in Dublin, with a professor in Waterford seminary, and with the professor of dogmatics in the national seminary at Maynooth. The next stage involved lecturing in ‘neutral territory’, with a chairman to open and close proceedings. I lectured on such subjects as ‘Conscience, Authority and the Bible’, and ‘Depression’. I even lectured in one Roman Catholic seminary on the defects in Rome’s view of the way of salvation.

Meanwhile God was stirring the few Irish pastors, evangelists and churches to prayer and evangelism. New churches began to appear all over the Republic. The little church in Cork developed daughter churches. Most encouragingly, as new churches began, they were equipped with pastors from Roman Catholic backgrounds, able to understand the people’s struggles of conscience. The Irish Bible School in County Tipperary came to birth. Christian work among students went forward.

Kilkenny

One of the most remarkable developments in the last fifteen years has been in a Presbyterian church in Kilkenny. This was once, like so many Protestant churches across Ireland, a small relic from the old days of English ascendancy. But God stirred his people there to pray. A prayer meeting had been going for forty years (‘ yes, I said forty!). They prayed that the Lord would send them an evangelical minister.

Then at last God gave them John Woodside, an ex-schoolmaster. Having visited the church, I am impressed by the fact that Scripture has played such a central role in the many conversions that have taken place there. The work has been advanced neither by gimmicks nor by the exaltation of a preacher. Rather, the Lord has been given all the glory.

Southern Ireland as a whole is a changed and changing land. Roman Catholicism, like Protestantism, has its liberal theologians. It has seen a staggering drop in the numbers of men offering for its priesthood. This decline has been accentuated by greatly publicised moral lapses. People are open, as never before, to the gospel. God is calling former Catholics to come to the Saviour, and then some into pastoral ministry. Today we face the challenge to pray that God would send labourers to this harvest field, so ready for reaping.