There are several inscriptions on the base of Paul Kruger’s statue in Church Square, Pretoria. One of them credits him with never having made a political decision without relying on the Scriptures as his guide. He became convinced that these decisions had divine backing. Certainly, until 1994, a close alliance existed between the politically dominant whites in South Africa and the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC).

In fact, the first European settlers did not emigrate to South Africa for religious reasons. They were farmers and not missionaries. They set up the Dutch East India Company in the Cape. While the religious element was prominent among French Huguenots, these were fewer in number than the earlier Dutch settlers.

But most of these various settlers were, indirectly at least, the products of the Reformation, coming with a background of Reformation values. Thus no Catholic worship was permitted until 1804 and, although the Roman Catholic Church is now growing rapidly, it still comprises less than 10% of the church-going population.

Developments

Ministry to indigenous peoples commenced early in colonial history. The Dutch felt a spiritual responsibility to their subjects and by 1681 over a thousand slave-children and forty adults had been baptised. George Schmidt, a Moravian, arrived in Cape Town in 1736 with the specific responsibility of reaching the Khoi (Hottentot) people. The London Missionary Society was an early entrant to the country — in 1799 Van der Kemp arrived at the Cape and together with other workers established mission stations on the eastern frontier and in the northern Cape.

The DRC continued to grow in influence, though internal divisions developed in the mid-nineteenth century. The Dutch, who had trekked into the interior to escape British domination, established their own new churches and many of these separated from the original church to form the Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk. A further breakaway occurred when a number of rural churches resisted what they felt to be liberalisation of the mother church, and formed the Gereformeerde Kerk.

Misleading statistics

The Christian faith has spread dramatically among Africans during the twentieth century. In 1900, approximately 20% of black Africans considered themselves to be Christians; today more than 75% make such a profession. Some 90% of South African whites, 85% of coloureds, and 15% of the Indian population profess to be Christians. While these numbers sound encouraging, the Christianity is to a large degree nominal. Attendance at worship and participation in church life is far lower than these statistics indicate.

For example, one of the first areas to be developed in Soweto was a community known as Dobsonville. A government census in 1996 put its population at 80,000. According to the census, 50,000 people in Dobsonville were adherents of local churches. Yet on any given Sunday morning no more than 5,000 people can be found in the 25 churches serving Dobsonville.

Pluralism

South Africa’s government now takes a pluralistic approach to religion. Its Christian history is reflected in the fact that prayer and religious instruction still take place in schools, and limited time is given on national radio and television for religious services. The national constitution talks of being in ‘submission to Almighty God who controls the destinies of nations and the histories of peoples’.

Prior to South Africa’s independence in 1994 the government supported and defended the Christian message, albeit a ‘gospel’ interpreted by and promoting apartheid. Christians who opposed apartheid were repudiated and persecuted. Little wonder that many people see Christian practices as ‘vestiges of the apartheid era’.

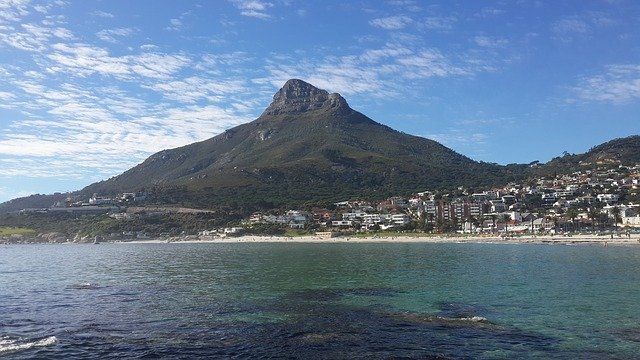

The ‘1999 Parliament of World Religions’, held in December in Cape Town, was much more to everyone’s liking. Cape Town was carefully selected as the ideal location for this gathering. The theme of the conference was ‘A New Day Dawning: Spiritual Yearnings and Sacred Possibilities’! More than 700 workshops attracted 8000 delegates from around the world. One of its stated goals was to unite the religions of the world. That objective accurately reflects the opinion of many within the religious communities of South Africa.

Post-denominational era

So what is the spiritual condition of South Africa today? Few discerning individuals are happy with the situation. Most churches are nominal. Islam is gaining in momentum and Muslims hold a disproportionate number of political offices compared to the population at large.

The weakness of the church is seen not only in the decreasing percentage of worshippers on Sunday (a 25% drop since independence, five years ago), but also in the lifestyle choices of South Africans as they rush to catch up with western secular values. Literally millions have dropped out of church activities altogether.

The church is also moving rapidly into a post-denominational era. The region surrounding our Baptist church here in Durban is a microcosm of the country at large. Most Christians in Durban are charismatic and centre their worship on music. Very few would give a high priority to the preached Word of God.

New, independent, Charismatic churches have sprung up across the country. Known as African Independent Churches (AIC), they place an emphasis on ancestor worship. In the past they would have been considered cults. While there is much enthusiasm in their gatherings, there is scant evidence of the fruit of regeneration in the lives of those who attend.

The older churches are in steady decline, many of them losing members to these new churches. In an attempt to arrest this situation many mainline churches have themselves become charismatic. This spiritual decline is dramatic in the black townships and urban areas, where there has been a large movement into the AIC.

Not surprisingly, with this lack of biblical teaching, the Roman Catholic Church is also growing rapidly. A recent government census shows it is now the second largest denomination after the rapidly declining Dutch Reformed Church.

In the past months the theological training schools at Rhodes University, the Witwatersrand, and the University of Cape Town have essentially closed their doors. Evangelical training schools are, however, faring much better. A promising statistic is that more than 1000 students from neighbouring countries are receiving tuition in South Africa in full-time theological institutions.

Doctrines of grace

I view the South African spiritual climate from the perspective of a Baptist minister holding to a Reformed, evangelical theology. Others might see the spiritual situation here as essentially healthy, especially in comparison to Europe. However, in my view, South Africa is speedily catching up with Europe in its zeal for secularisation and religious pluralism.

There are few theologically Reformed believers. A handful of annual conferences cater for those who love the doctrines of grace. There is one theological institution that is explicitly Reformed. Without doubt, there is a famine of the Word of God in the land.

There are not nearly enough preachers with a solid grasp of Scripture and able to communicate adequately the gospel message. As grave as the situation is in the white communities, the plight of the coloured, Indian and black communities is far worse.

Those who do love the Scriptures face persecution in a way they have not done previously. The grossly secular nature of the workplace brings persecution to those who unashamedly witness to their faith. African churches are targets of gang violence, and Islam is clearly a militant threat to the cause of Christ. My prayer is for a resurgence of biblical teaching and preaching in South Africa. Thankfully, there are still some churches and individuals seeking to make the Bible central to their worship and daily lives.