The changing political situation in South Africa has given rise to major changes in theological education over the past decade, changes that are in line with worldwide trends. Until about ten years ago, anyone wanting to train for the Christian ministry or the mission field could enrol at a university or Bible college. But things have been changing.

Past attitudes

Several universities were recognised as training institutions for the major denominations. Stellenbosch, Potchefstroom and Pretoria universities trained students for the Dutch Reformed, Gereformeerde and Hervormde churches. Rhodes University trained students for Anglican, Methodist and Presbyterian churches.

The training offered by Bible colleges was not recognised by the universities, being considered inferior to their own courses (which was not true). Consequently, universities would not grant degree-credits to Bible college students.

The universities had a monopoly, for they alone could confer degrees. This situation placed English-speaking Evangelicals in a dilemma since, for the most part, the theological faculties of South African universities are either liberal or neo-orthodox.

Nevertheless, many Evangelical pastors wanted their qualifications to be recognised academically, and still decided to study at the universities. Many obtained degrees through the University of South Africa (UNISA), one of the largest distance learning training institutions in the world.

UNISA offered a mixture of liberal, neo-orthodox and evangelical theology, and one may well ponder how far the exposure of ministerial students to non-evangelical theologies has affected the evangelical churches today!

New trends

However, all this has begun to change as a result of recent falling university student numbers combined with the growth of the inter-faith movement. Both have impacted strongly on the South African university scene.

With dwindling numbers, some universities have been forced to close their theological faculties. Others have combined them with their faculties of religious studies.

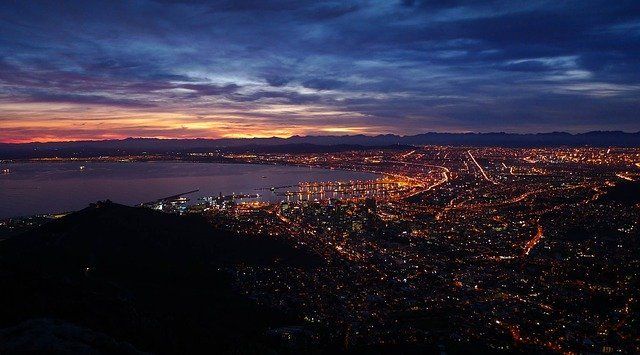

For example, Rhodes University had already downgraded its theological faculty to a department, but will be closing it down completely at the end of this year. The University of the Western-Cape is in the process of closing its faculty of theology. The University of Durban-Westville has combined its theological faculty with what is known as a ‘Centre for Religion’ and placed it in the faculty of arts.

At the same time, student numbers at Evangelical Bible colleges have been increasing and, in a switch of attitude, the training given by Bible colleges is being recognised by universities.

Students at various Bible and theological colleges can study for a university degree at their own colleges, and maintain their own denominational emphases. For example, the three Baptist colleges in South Africa are affiliated to the Universities of Zululand, and Pretoria. The interdenominational Bible Institute of South Africa in Kalk Bay (among others) is affiliated to the University of Potchefstroom.

Bible colleges today

Many of our Bible colleges have well-trained and experienced staff and well-equipped libraries. One has a faculty as strong academically as the best university theological faculty. For this reason, some Bible colleges are applying to the government for the authority to confer their own degrees.

Another recent development in the Bible colleges has been the introduction of ‘distance learning’ programmes of study. These have been introduced to expedite the training of church leaders, especially in rural areas, and to assist students who cannot afford the cost of full-time study.

The majority of these students are non-white. The Baptist College in Cape Town has been running a ‘Satellite Centre Programme’ for a few years. It has 330 students registered, studying in 52 centres.

New challenges

Since the ANC came to power in 1994, the well-educated Black middle class has grown significantly in influence and numbers. Unless the standard of education of black pastors is improved, there may be little impact made for the gospel on this rising group. Although our colleges are not yet attracting a large number of South African black men, it is interesting that they are drawing men from other parts of Africa.

There is no doubt that theological education is in a period of transition. Some of these developments should have a positive impact on the life of the church. But they will have to be watched carefully lest fresh theological errors are introduced into the churches. One of the greatest threats is the move to contextualise theology into ‘a theology for Africa’.

Those committed to Reformed theology are troubled that most of our colleges are either charismatically inclined or without a robust, evangelical, theological emphasis. As far as this writer knows, there is only one Bible college in all of South Africa where the majority of the staff are committed to Reformed theology.

To counterbalance this rather negative perspective, some church leaders are beginning to see the need for local churches to take their rightful biblical responsibility for the training of leaders at all levels.