Aboriginal Vedda inhabiting the island were conquered by Sinhalese, who came from north India during the 500’s B.C. In the third century B.C. the island became a major centre of Buddhism. Tamils arrived from south India from 100 B.C. onwards. Conflict between Sinhalese and Tamils resulted in Tamils controlling the northern half of the island and Sinhalese the south.

Europeans were attracted to the island by the spice trade. The Portuguese first colonized it in A.D. 1505, to be followed a century later by the Dutch, and then in 1796 by the British. Britain declared Ceylon a crown colony in 1802. Under British rule Tamils had access to British education and rose in administration and the civil service. Many other Tamils immigrated during the nineteenth century and found work on the rubber and tea plantations. Tea was grown in Ceylon from the 1880s.

Nationalistic feeling amongst the Sinhalese, however, grew during the early twentieth century. In February 1948, fifty years ago this month, Ceylon was granted independence. Buddhist religious fervour increased. Millennial politics, that visualized the establishment of a Buddhist utopian state, were given a further boost in 1956, with the election of S. Bandaranaike as prime minister. Ceylon’s government quickly abandoned its original multi-racial polity in favour of positive discrimination favouring the Buddhist Sinhalese – symbolized by the adoption in 1956 of Sinhala as the official language. Tamils protested against the language law and there were riots. In 1959 Bandaranaike was assassinated.

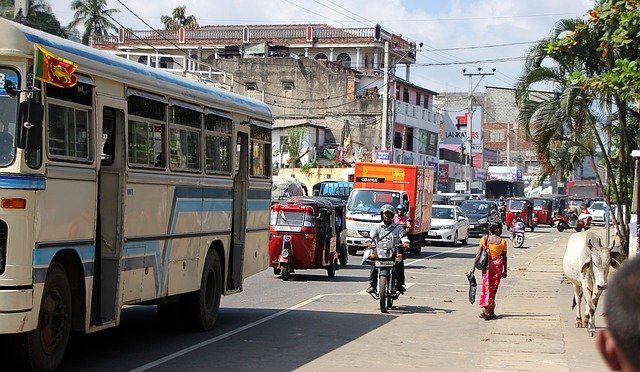

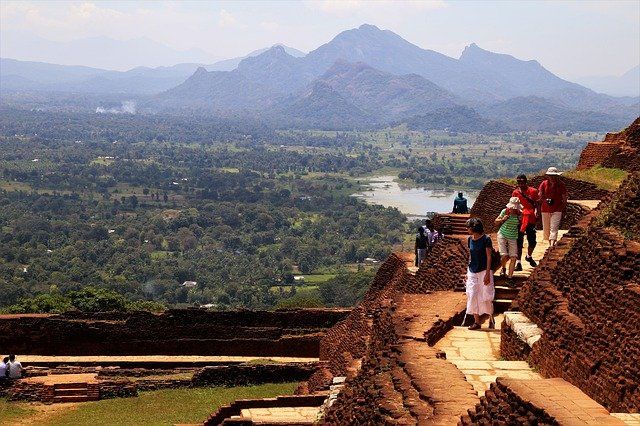

Bandaranaike’s widow continued her husband’s socialist and religious policies. She nationalized numerous Western-owned businesses and made Ceylon part of the Third-World, ‘nonaligned’ movement. In 1972 she declared Ceylon a democratic socialist republic, giving it the new, Sinhala name of Sri Lanka or Resplendent Island. Economic conditions deteriorated and in 1977 Mrs Bandaranaike was defeated at the polls by J. Jayawardene.

Jayawardene pursued Western-style capitalism and won re-election in 1982. The progressive restriction of Tamil minority interests by the State continued and there emerged a violent Tamil separatist movement, spearheaded by the ‘Tamil Tigers’. These demanded Tamil homelands in the north and east of Sri Lanka. Inter-communal violence between Tamils and Sinhalese increased, and developed into full-scale war by 1984. The tourist industry, foreign investment and overseas aid all collapsed. There was widespread loss of life.

India attempted to mediate, and in 1987 the Colombo Accord, promising some autonomy to the Tamils, was signed by both Jayawardene and the Indian prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi. An Indian peace-keeping force of seven thousand men was dispatched to Tiger-controlled Jaffna. Sinhalese ‘hard-liners’ declared the accord a ‘sell-out’ to the Tamils and the peace agreement soon broke down. Indian troops became heavily involved in fighting against the Tigers.

Thereafter civil war continued, as did the exodus of Tamil refugees. Jayawardene was replaced by R. Premadasa in 1988 and India withdrew its troops in 1990, with the conflict still unresolved. Since then the Tamils have experienced heavy defeats, yet remain a potent destabilising influence, and were probably responsible for the assassination of Premadasa in 1993.

In 1994 Sri Lanka elected its first woman president, Chandrika Kumaratunga, who has tried to introduce more democracy and broker a new rapprochement between the Tamils and Sinhalese, so far unsuccessfully. In all, the continuing violence has claimed at least 50,000 lives, with many persons still missing and unaccounted for.

Church history

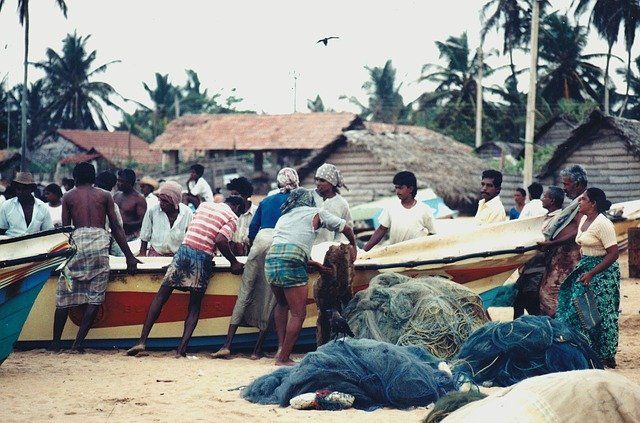

There are early accounts of Nestorian Christians being on the island, but little evidence of Christian influence of any kind until the sixteenth century, when the Portuguese introduced Roman Catholicism. This took root particularly among the Karawa fisher and Salagama cinnamon castes. Later, Dutch colonization brought the Dutch Reformed Church, which drew many of its ‘converts’ from the Catholic community. The Dutch translated the Bible into Tamil. But their ministers were closely allied with the political establishment, and it is not surprising, therefore, that their converts were both numerous and ephemeral. When the British replaced the Dutch, most returned from Protestantism to Catholicism.

The London Missionary Society worked in Ceylon from 1804 to 1812. Baptists arrived in 1812, Methodists in 1814 and the Church Missionary Society in 1817. American missionaries also worked in Jaffna. Although these missionaries were working in the heartland of Buddhism, they did initially gain some converts. This trickle expanded to a flood between 1860 and 1885, but after that it dried up in the face of an aggressive Buddhist ‘revival’ amongst the Karawas.

After independence in 1948, successive Buddhist governments restricted missionary activity and, by the 1960s, had taken over the running of Christian schools. During this period Christians were often portrayed as mere representatives of colonialism. This was, perhaps, not altogether unjust, for the Christian Church in Sri Lanka at that time was labelled by some the ‘most nominal’ in Asia. Certainly, during this century, the established churches there have been in the forefront of the ecumenical movement, exemplifying its religious pluralism and moral relativism.

The traumas of civil war have increased the openness of many people from different backgrounds to new ideas. From 1983 to 1997 thousands have joined the churches, perhaps more than at any other time in the island’s history. A resurgence of evangelistic zeal amongst lay-Christians in all denominations has resulted in converts from all sections of society, with the formation of new churches in the villages. On the other hand, the recent resurgence has been heavily influenced by Arminianism and Pentecostalism.

Current situation

There have been serious social consequences from the continuing war. One observer has written: ‘Ethnic conflict has had a pulverizing effect on the traditional social order. Widespread social dislocation … has led to a breakdown in the traditional authority and kinship structure and the bases of communal solidarity. Separatist-inspired ethnic cleansing, State-sponsored extra-judicial killings, and disappearances, have contributed to the general militarization of social life, evidenced by the emergence of a gun culture’ (C.R.A. Hoole).

Today there are still far more Roman Catholics than Protestants in Sri Lanka. Roman Catholicism there shows syncretistic tendencies towards Hinduism and Buddhism. For example, there are striking correspondences between Buddhist, Hindu and Catholic ‘pantheons’ of idols, as well as between the cult of Mary and the cult of Pattini-Kannaki, the chief deity of the fisher castes. Catholicism is also deeply divided by the civil war, having assimilated racial and caste attitudes from the earliest days. Thus during the anti-Tamil riots of 1983 Sinhalese Catholics conspired with Sinhalese Buddhists to attack Tamil Catholics.

There are about 160,000 Protestants in Sri Lanka today, in about 1100 local churches. Leadership is said to be often authoritarian in style, with some leaders having enriched themselves from Western donations. While the Dutch Reformed Church nominally adheres to the doctrines of grace, it too has become ecumenically involved. Sections of the Anglican Church are pluralist, accommodating Buddhist and Hindu prayers in their services. The Bishop of Colombo, Kenneth Fernando (who is also leader of the National Christian Council of Sri Lanka), has avowed, ‘It may be that the key to ethnic and cultural pluralism lies in religious pluralism.’ He has also remarked that to say salvation is through Christ alone is as ‘arrogant’ as saying that Sri Lanka is for the Sinhalese alone!

Just under half of the Protestants (75,000) would claim to be evangelical, with two-thirds (50,000) of these being Pentecostal or charismatic. Many of the latter belong to churches planted within the last twenty years. Within the Greater Colombo area alone there are nearly four hundred such churches, some very large. The ethos in these is said to be an ecstatic religiosity which puts personal devotion before all else and proves itself by unquestioning submission to human leaders.

Reformed witness

As to the young, relatively small, but burgeoning Reformed witness, a local Tamil Baptist pastor writes, ‘The Lord has graciously set up a few independent local churches, which deeply embrace and subscribe to the doctrines of grace … There are eight or nine such churches existing in Sri Lanka … Particularly four churches come together once a year for a Reformed ministers’ conference, and once in two years for a family conference. An informal fraternity called the Evangelical Reformed Fraternity of Sri Lanka was established in 1993 for the purpose of mutual edification and support … in addition to organizing these conferences. Newly converted members of these Grace churches are slowly being taught the glorious doctrines of grace. At the same time there are a few non-charismatic, evangelical independent assemblies which are very sympathetic towards Calvinistic doctrine, while some openly embrace the doctrines of grace… Some of the Grace churches have established new churches recently by sending new evangelists to new areas.’ However, many thousands of villages still remain without an evangelical witness.

A small but vigorous Reformed literature work has been taking place under the auspices of these Grace churches and certain theological colleges. Some of these churches are also planning to publish their own Reformed literature in Tamil and Sinhala.

Conclusion

Reginald Heber’s (1783 ‘1826) hymn is still an accurate description of communities gripped by idolatrous religion, violence and fear, and served by a majority of churches, tainted with Western theological errors:

‘What though the spicy breezes

Blow soft on Ceylon’s isle;

Though every prospect pleases,

And only man is vile;

In vain, with lavish kindness,

The gifts of God are strown;

The heathen in his blindness,

Bows down to wood and stone.’

The only lasting answer to Sri Lanka’s problems is the glorious gospel of Jesus Christ, a gospel of whose tenets many are still ignorant. Christ alone makes peace between God and elect sinners, and he does so by the blood of his cross. He alone reconciles bitterly divided people to one another in the bonds of divine love. The gospel of grace is the only force that can turn Sri Lanka’s ‘tear drop’ island into the ‘pearl’ of the Indian Ocean.