As a Dutchman I have enjoyed living in England for more than six years and, in this article, I hope that British readers will be able to taste a bit of Dutch Christianity!

Reformed churches in Holland and England have interacted with the rest of society in markedly different ways. Otherwise, the scene is similar in both countries, with a large variety of churches and a marginalised Christianity. The total number of Dutch Evangelical Christians (with their children) is estimated at 1.3 million.

Protestant denominations

The ‘established’ Netherlands Reformed Church (NRC) claims 2 million members, but many of these are nominal. The NRC is entering into union with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (RCN). The RCN has 750,000 people and a declining membership. Evangelical influence within these two denominations is strong locally but muted nationally.

Three others – the Christian Reformed Churches (CRCN), the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (Liberated) and the Netherlands Reformed Congregations – are Evangelical and Reformed, and co-operate with one another. Their combined membership is 230,000, including children.

Independent Evangelical churches, including Baptist, Brethren and Pentecostal, have grown significantly in the past five decades. They have partly drawn new members from the traditional Reformed churches, and amount to about 60,000.

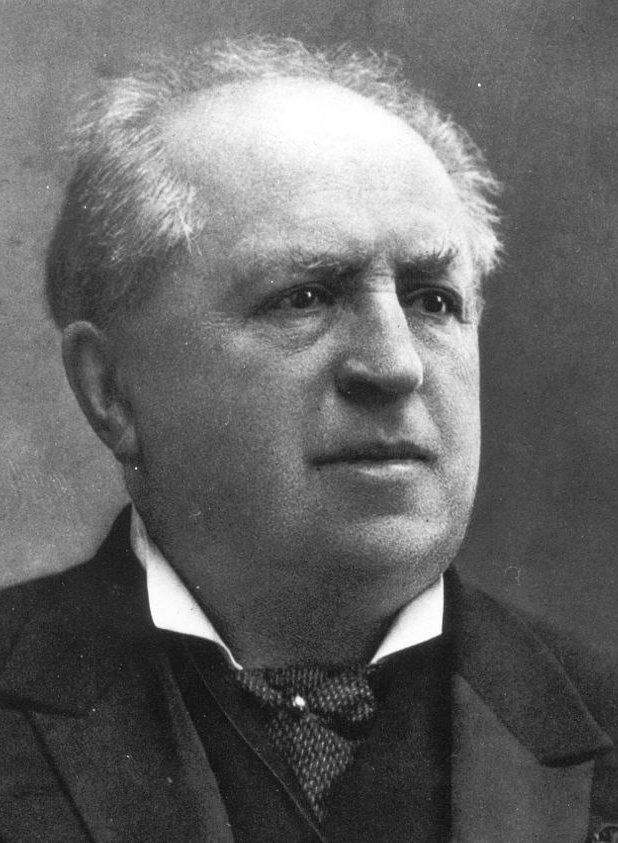

Abraham Kuyper

During the past century, Christian political parties, schools, hospitals, broadcasting organisations and trade unions have had a strong influence on Dutch society. This unique social influence sprang from the work of Abraham Kuyper (1837-1922), a Reformed pastor and theologian and one-time Prime Minister of the Netherlands.

Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones spoke of this Kuyperian tradition in a paper given at the 1975 Puritan Conference in London. He said that it presented a ‘most extraordinary and striking opposition to the whole [secular humanistic] principle of the French Revolution’.

Kuyper’s thinking was rooted in seventeenth-century Dutch Calvinism. Crucial to his view was an holistic understanding of Christ’s redemptive Lordship, which he derived from Scriptures like Colossians 1:20: ‘by him to reconcile all things unto himself – whether they be things in earth, or things in heaven’, and Matthew 28:18: ‘all power is given unto me in heaven and in earth’.

Creation mandate

Kuyper taught that God first gave Adam lordship over creation to enjoy and use it for God’s glory. Implicit in this mandate was man’s eventual vice-regency over spheres like technology, art and politics.

At the Fall, Adam turned creation to his own sinful ends and, for this reason, it too was brought under God’s curse (Genesis 3:17; cf. Romans 8:20-22).

But the created order, like man, has not been abandoned by God. Christ became incarnate, firstly and primarily, to fulfil the moral law for sinners and to suffer and die in their place (2 Corinthians 5:21). Secondly, as the Second Adam, he assumed Adam’s original role as lord over creation.

Christ by his redemptive work restores the sinner’s relationship with God, and man’s rule over the created order. In other words, Christians now reign with Christ over the earth, as well as being citizens of the Kingdom of Heaven and members of his redeemed Body.

Kuyper was not pursuing worldliness, but was arguing for the realisation of Jesus Christ’s Lordship over the whole world. He made the famous statement: ‘There is no square inch which Christ does not claim “Mine!”‘ Christ’s Lordship of life includes its culture, politics, commerce, science and technology.

Mixed picture

Today in the Netherlands much of his vision has been lost. Legislation is more humanistic here than anywhere else in the world. Evangelicalism is permeated by a ‘feel good’ approach. Felt ‘experiences’ of the love of God are seen as more important than our responsibilities towards God, man and creation.

Spiritual consumerism abounds. For example, Evangelical broadcasting has turned into spiritual ‘entertainment’. Active Christian participation in society is deemed necessary, but left to ‘professionals’, as church members withdraw from society rather than act as salt and light.

Some believers have moved from urban areas in the west of the Netherlands to the ‘Bible belt’ areas elsewhere in the country. Churches and Christian schools are closing down in the major cities, and Christian witness is disappearing from those needy areas.

Thankfully, there are also encouragements. Evangelicals from various backgrounds are interacting more positively than before. They are concerned to combine zealous evangelism with their positive view of Christ’s Lordship.

The major challenge for the churches today is to equip God’s people for their many-sided service in his Kingdom. The future of Christian witness in the Netherlands may well be bound up with this reconsecration. May God grant us wisdom and strength to advance his Kingdom!