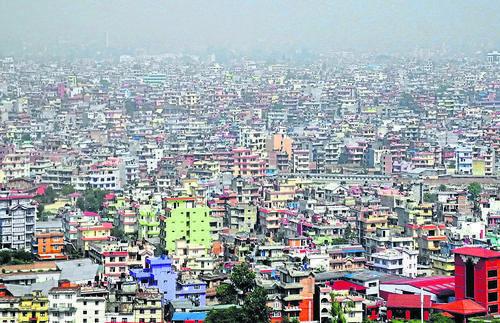

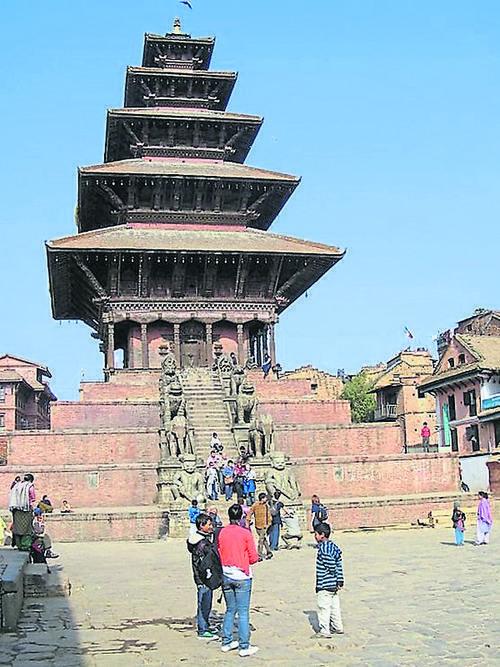

Down the valley from Kathmandu, the ancient capital of Nepal, rests an even older city. In Bhaktapur, the timeworn traditions of Hinduism sink as deep into the dry soil as the white-capped Himalayan mountains rise in the background.

Bhaktapur looks like it was built one brick at a time. Narrow, brick-paved city streets are lined on both sides by three-story brick buildings, built into each other over time to become a continuous wall of homes and stores. An occasional small tractor or motorcycle putters slowly by, joined for a few steps by a wandering goat or chicken or dog.

Delivery men on bicycles snake through the streets, weaving past groups of children walking in school uniforms, past women washing clothes in a street gutter, around bent labourers carrying huge bundles of straw on one shoulder or men crouching and forming spinning clay into a bowl; past groups of unemployed young men with nothing better to do than stand around, past tranquil street merchants waiting for customers, past holy statues of bronze rubbed gold by the touch of its worshippers; past sacred cows tied up, past large silent temples attracting the cameras of a few tourists, around small and active roadside shrines flowing goat blood into the street, and under the eyes of quiet gawkers hanging their heads from upper story windows to watch it all.

These poor, dusty and lost streets of Bhaktapur were once haunted and hunted and bloodied with human blood by a home-grown thug named Suraj Kasula.

Rise of a gangster

Suraj, now 27, was an unlikely gangster. He was born into an orthodox Hindu family that still worships and offers blood sacrifices to their 330 million gods and goddesses.

‘My childhood had very strong similarities to the Old Testament’, Suraj said, ‘especially in regard to the ceremonial laws. Like every orthodox Hindu family, every year our family’s sins were transferred onto a male goat and then we sacrificed it. We collected and sprinkled its blood on the doorposts of our house’.

But the sacred bloodshed and religious devotion were powerless to stop Suraj from the allurement of a life of crime, which began when he was 16. With jobs hard to find in the city, the notorious life of a thug appealed to him, and Suraj turned to armed robbery and formed a knife gang.

‘It’s very easy to form a gang in Bhaktapur, because most of the youth don’t go to school or have jobs. We kept an arsenal of knives and steel rods in case a fight broke out. The gang and the crime became my satisfaction. I found joy in it’.

‘We would go into someone’s flat and ask for money and they would give it. If there was nobody home, we would steal it without any threat. We used the money to buy marijuana. Nobody would say anything. Over time, I became locally well known, and the people in my village were afraid of me. Everybody knew I was a thug. My bad name and fame began spreading’.But mostly he was after money, not blood. ‘We mainly threatened people and demanded money. Then we would threaten them that, if they told the police, we would kill them. We raised protection money from local start-up businesses in our area.

Praying for his death

His notorious thug life was spreading intimidation, but it was also incubating anger and hate in his heart.

‘I grew angry. If a man walked down the street and stared at me, I would beat him. One time a man was staring at me with no reason, which provoked me. I approached him, but he went up into a city bus. I ran in front of the bus and made it stop. The driver became scared and stopped.

‘I went inside the big crowd; I pulled the man out and beat him on the street. He was crying for help, but nobody dared to help him. Apart from an occasional fight with a rival gang, fighting was rare, because most people were scared of me’.

Suraj rode the city buses, but never paid a full fare. Once, a conductor of a bus confronted him. Bad move. Suraj’s rage took over. He battered the conductor inside the bus and then stepped out and calmly walked away with the conductor’s blood all over his shirt. His wrath was responsive and proactive. Any whiff of a gang reprisal from others was pre-empted by his own attack.

Suraj tattooed his body, a cultural display of a thug’s hardness, meant to accentuate his intimidation. No respectable person in Nepal has tattoos. The marks on the surface of his skin were the outer evidence for the gnawing decay within his soul.

He broke the hearts of his family members who watched his decline. ‘My family and whole village wanted me to die, because I was ruining their children’s lives. Everybody knew people were coming to our gang, which eventually grew to sixteen. Our parents were powerless to do anything. My family was very unhappy, and the whole village would offer prayers to their gods that I would be killed in a knife fight’.

Hating, being hated

Suraj made a living off his hatred. Hating came naturally, especially when it was directed at cops.

His gang stored weapons, mostly knives, machetes and steel rods, in the home of a local shopkeeper, who also supplied Suraj and his gang with pot. Benefitting from the protection, the shopkeeper was loyal, but his wife was uninformed of the weapons in her home.

One day she discovered the weapons hidden in the bedroom. She called the police, who showed up in civilian clothes just as Suraj was arriving at the shop for a new supply of marijuana. The police appeared and immediately suspected Suraj as the owner of the weapons. He was arrested on the spot.

‘As soon as I entered the police station, every cop beat me as if I was a football. Then I was locked behind bars. In Nepal there are few human rights for criminals; they can kill you. They tortured me and put me in prison for a month, until my family came and paid my freedom with what was, for them, six-month’s salary’.

His release caused further tension in his family and more angry fights with his father. And the police beating did nothing to entice him away from the gang life. It actually fuelled his rage and unlocked new depths of hate.

‘When I came out of jail, because of the torture, I knew I would kill the police officers who did this. Every year in Nepal, there’s an annual festival to celebrate the new year, a big festival that often results in riots and fights with police. In past years some policemen were found dead in the street gutters. I planned to do the same and went to the celebration looking for the policemen who brutally tortured me in jail.

‘I didn’t find them, but my rage had now spread against the whole police force. I started throwing stones randomly. Police were hurt and were furious, and they pursued me and I ran. Eventually they trapped me, surrounded me, and nearly killed me with another round of beatings. They were hurt and furious. I nearly bled to death. Some of the policemen stopped the beating because they assumed I would die in the street’.

Dark despair

Suraj was taken from the street to the hospital and recovered enough to be arrested and thrown in a holding cell for 26 days. ‘My family, who is not rich, brought more money to set me free again’.

After his second arrest, his infamous reputation reached new heights of intimidation. Never was it easier to recruit, never was it easier to mug for money.

But after his second imprisonment, and with little hope of a third financial release from his family, Suraj took his mother’s advice and returned to school. He found ways to get into fights there, and would often just wait for a teacher to get deep into a lecture before jumping out of the classroom window to waste the day with drugs and drink. Only the fact that a police station was next to his school deterred him from beating teachers.

By this point, the joy and thrill of the gang life was eroding, exposing a dark despair in his heart. ‘I often thought about killing myself’, he said. ‘I took no pleasure in my life. I had no satisfaction. I had no love from my family. I fought often with my father. I knew I was going to hell, based on Hindu teaching.

‘I was a disgrace to my gods and to my family and to my village. They were praying for my death. Everyone was telling me I was not worthy to live, but I could not kill myself, because I was more afraid of death and hell. I had no hope’.

Suraj was too empty to live, too scared to die, too despised to be loved. ‘When I was most detested’, he recounted, ‘God acted on me’.

Collision with cow-eaters

Joy came to Suraj by surprise. Through a classmate and local neighbour, he walked to school with a closet ‘cow-eater’.

‘Cows are sacred in Nepal, and Christians are cow-eaters. Since all Westerners are Christians, they were all cow-eaters. That was my background. I honoured the cow as a goddess and worshipped her. But my neighbour and I became friends, and then eventually one day he told me about Jesus. When I discovered he was a cow-eating Christian, I got so angry I almost knocked him down. But because he was very humble and kind, I did nothing to him.

‘He told me Jesus could forgive my sins. I argued with him and tried to provoke his anger by accusing Christianity as a religion of money, since most churches in Nepal are supported by Americans. But nothing I said could provoke him. That amazes me to this day’. The intimidating hatred of Suraj had met unflinching courage.

This same friend invited Suraj to church for Christmas, a risky move with unpredictable consequences. But Suraj agreed. More than anything, he was enticed by the modern music. He was drawn to American bands like Nirvana, and to instruments like the electric guitar and drums, sounds rarely experienced in Nepal.

‘So I went to the church during Christmas 2006, to see the instruments, hear the music and see the musicians, especially the girls. I walked into the church for the first time, dressed like a thug and with tattoos, and the congregation was frightened. But they did not cast me out.

‘I was the outcast, a disgrace to my gods and goddesses and to my family. But this church cared. I started going to church every week, but I firmly rejected Christianity and kept my focus on the instruments and the music. But I could feel something in my heart, a voice drawing me. But I suppressed it’.

The God who turns his cheek

The pastor of the church gave Suraj a copy of the Bible to read. ‘One night as I was reading the Bible, just as ordinary literature, and studying Matthew’s Gospel, something amazing stopped me that I had never ever seen or heard before: “If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also” (Matthew 5:39)’.

It was like cold water to his face. Suraj was familiar with gods of wrath and the warning of the Hindu god Krishna, who promised to descend to earth in order to ‘deliver and rescue the pious and to annihilate the miscreants’ (Vedas 4:7).

‘I had heard of many gods who love righteous people’, Suraj said, ‘but never had I heard of a God who loves sinners and says, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” and “If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also” (Matthew 5:39, 44).

‘But above all, I would never expect a God who would die for sinners! Having read of the love of Christ towards sinners, I could make a sharp distinction between Krishna and Christ. All the teaching that I had ignored in the church powerfully overwhelmed me. Krishna came into the world to destroy sinners; “Christ came into the world to save sinners” (1 Timothy 1:15).

‘Krishna hates sinners; Christ loves sinners and died for them (Romans 5:8). That night I read Matthew 5:39. I could no longer resist God. His invincible grace overcame me, and I burst into tears, and I trusted Christ as my personal Lord and Saviour’.

To be concluded (ET, January 2017)

Tony Reinke

© Desiring God Foundation. Source: www.desiringGod.org (John Piper)