C.S. Lewis was born one hundred years ago

Ask 100 Christians which writer has most influenced them, and one name will recur again and again: C.S. Lewis. Even those who disagree with him on some important points have been influenced for the good by his writings.

Search for joy

Clive Staples Lewis was born in Ulster on 29 November 1898. When he was nine his mother died of cancer. His relationship with his father was difficult and strained, and at the age of ten he was sent to boarding school. No other experience in his youth — not even the trenches in France in 1917-18 — seems to have given him so much unhappiness as his schooling. Finally, after a period with a tutor in Surrey, he was awarded a scholarship to Oxford. He eventually became a don, first at Oxford and then at Cambridge. His search for joy led him to Christ, the source of all joy, and he became one of the foremost Christian apologists of his time. This month marks the centenary of his birth and the thirty-fifth anniversary of his death.

The life to come

Lewis’ contribution to Christian understanding was enormous, and I have no intention of reflecting negatively on his work. I am the living proof of his success. It was the relentless logic and passionate conviction in his book Mere Christianity that led me to Jesus Christ. But in this article I would like to examine one area where evangelicals would disagree with him, namely, the life to come.

Hell

C. S. Lewis believed in offering prayers for the dead. He says that 1 Corinthians 15:29 and 1 Peter 3:19-21 imply that ‘something can be done for the dead’, and infers that we can pray for them. I do not think this inference can be safely made. Paul is not advocating baptism for the dead — merely acknowledging that the Corinthians practised it. In any case, we are not told what the practice signified. It might have been no more than an act of testimony on behalf of believers who had died before they could be baptised. Peter, on his part, when he says that Christ ‘preached to the spirits in prison’, is describing an action carried out by the Lord Jesus — an action in which we are not invited to participate.

Lewis says that if we are to pray for the living, even though God has already done for them all that can be done, why not also for the dead? ‘The action is so spontaneous, so all but inevitable, that only the most compulsive theological case against it would deter men’. I believe this is answered by Hebrews 9:27: ‘It is appointed for men to die once, but after this the judgement’. Let us pray for those we love while they are alive, or it will be too late.

Lewis affirms that, as we are immortal souls, hell is an eternal state. When a log is burned, the result is heat, gases and ash, and ‘to have been a log means now being those three things’. He surmises that, in the same way, there may be a state of ‘having been a man’, so that what is in hell is an ex-man. There is no biblical basis for such an idea, as the story of Dives and Lazarus in Luke 16 clearly shows.

Heaven

Lewis has far more to say about heaven than hell, especially in his private correspondence. Many of us could echo his words that heaven attracts us most, not when life is at its harshest but when life is good. ‘It is when there seems to be most of heaven already here that I come nearest to longing for the patria’. He likens these moments to the frontispiece which make us want to read the whole story. ‘Our Father refreshes us on the journey with some pleasant inns, but will not encourage us to mistake them for home’.

In The Last Battle, Lewis’ idea of heaven owes as much to Plato as it does to the Bible. Writing some 400 years before Christ, Plato groped his way towards truth with a surprising degree of insight. Thus Lewis believes that the scenes which will meet our eyes in heaven will be the perfect original of which this world is a pale copy. This is speculation, but Lewis is right in one succinct observation: ‘Heaven will display far more variety than hell’. Grace will perfect our nature to the full richness of diversity. Lewis affirms that it is not religion but God himself who will wholly occupy us in heaven, and that the joy which will characterise heaven will be of a far more momentous and less frivolous kind than we experience in our light-hearted moments on earth. ‘Joy is the serious business of Heaven,’ he declared, and in this at least he was surely right.

Purgatory

But of all Lewis’ writings on the afterlife, none is more fascinating than The Great Divorce, a work of fiction based on two separate premises. One of these we are bound to reject, but the other is a glorious truth, imaginatively expressed.

The first premise is a belief in purgatory. The story opens with a queue at a bus stop in purgatory. The bus is to take those who wish to go on a day trip to the outskirts of heaven. There they meet redeemed spirits whom they knew on earth, and who are sent to entreat them to accept the gift of salvation. All who accept this gift find that they have been in purgatory. For those who reject the offer and return there, it becomes hell. Lewis’ purgatory is a place where no man can live charitably with another, and sins which were indulged on earth loom literally larger than the soul. Thus, in purgatory, someone who in this life was a grumbler may become simply a grumble.

The Bible makes it clear that when we die, we will either be with Christ in paradise or else eternally banished from God’s presence. An impassable gulf stands between the place of the damned and the place of the redeemed. Lewis says he is ‘appalled by the degradation’ of Dante’s Purgatorio, and he rejects Thomas More’s Supplication of Souls in which purgatory is just a temporary hell. These ideas of purgatory, he says, are ‘disgusting and unhallowed’. Yet I have to say I cannot see how his purgatory in The Great Divorce is really very different from them. Lewis surmises that when God says to us, ‘Enter into the joy’, we shall reply, ‘With submission, Sir, and if there is no objection, I’d rather be cleaned first’, and that therefore purgatory will be a place of purification.

In contrast to this, the Bible paints a picture of a royal exchange in which our sins are cast away as far as the east is from the west and we receive in their place all Christ’s righteousness. This is a process to which we contribute nothing — it is all of his grace. I shall never be any more justified than when I was first saved. One of Lewis’ most revealing remarks comes in a letter: ‘I am almost frightened by God’s mercies: how can we ever be good enough?’ Although intellectually he grasps the doctrine of grace, it seems as though, emotionally, he struggles with its reality.

Solid realities

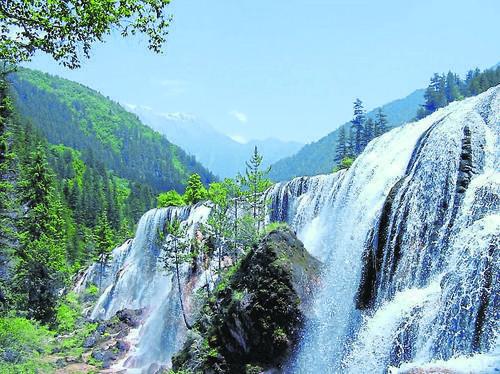

The second premise is that when we speak of spiritual realities, we should represent them as being immeasurably more solid and substantial than the material world. Thus, Lewis depicts blades of grass in heaven as jagged daggers, and the spray from a waterfall like thousands of diamonds. Only those who have been fitted by God to walk there experience the softness of grass and the dewiness of spray. Mortals appear as vague, wraith-like figures compared with the density of the spiritual matter. This is a truth which our generation has lost sight of. We think of ourselves in terms of sturdy tangibility, while those who have already passed into God’s direct presence seem almost phantasmal. Of course, in a very real (albeit metaphorical) sense, the reverse is true. Heaven is the ultimate reality.

The Great Divorce contains some golden nuggets of truth, superbly expressed. My favourite moment comes when a man who prides himself on having made his own way in life wants to be admitted to heaven on his own merits, not on the basis of what someone else has done for him. After pressing his point for a long time, he exclaims exasperatedly, ‘I only want my rights. I’m not asking for anybody’s bleeding charity’. The response comes, ‘Then do. At once. Ask for the Bleeding Charity’.

Like all of us, Lewis’ understanding of the next world was, at best, imperfect. At times, he strays into downright error. Yet we owe him a debt for keeping these matters before us, for reminding us that we are only pilgrims on earth and that everything we do in this life has eternal consequences. He sought to make Christian truth clear to the plain man and I, along with thousands of others, have daily reason to be grateful.