Mingling among the vast throng of worshippers converging on the Surrey Gardens Music Hall to hear the youthful Spurgeon was a middle-aged woman, petite and neatly dressed in black. Lines of suffering marked her face but the high cheekbones and resolute mouth added a look of courage and determination. Lavinia Bartlett was a regular member of New Park Street Chapel and for five years she had witnessed the spectacular increase of congregations as Spurgeon’s ministry attracted hearers from all parts of London and beyond. But now in 1859 Mrs Bartlett stood at a critical juncture in her life. The recent and sudden death of her husband during a virulent epidemic of cholera had left her a widow at only fifty-three years of age. In addition, her own health was in a precarious state. With a serious heart condition, she knew that any undue exertion could bring on symptoms which might prove fatal. It seemed that Mrs Bartlett’s service for God was nearing an end. In fact it was only beginning.

Converted whilst still a child, she had early displayed an unusual zeal for reaching the lost for Christ. Not only did she teach in the Sunday school at the age of twelve, but would also walk out to all the local villages and farmsteads and exhort burly farmers and their boisterous lads not to neglect the concerns of their souls. Marriage and family life had curtailed such activities for many years, but now, alone and far from well, Mrs Bartlett began to wonder whether God had further service which she could fulfil.

She had not long to wait. In June 1859 she was asked if she could step in at short notice to teach the senior girls’ Bible class. Hesitantly she accepted, but stipulated that it should be only for a trial period of a month, fearing lest it should adversely affect her health. Although only three teenage girls were present for her first Sunday afternoon class, by the end of the month the numbers had increased to fourteen and Mrs Bartlett was asked if she would consider continuing on a permanent basis. ‘If the Lord has given me strength for one month’s labour, he will be sure to give me strength for another month’ was her characteristic reply.

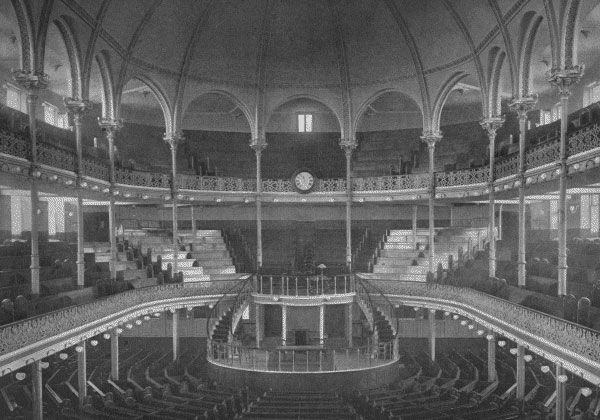

So began ‘Mrs Bartlett’s Class’ – an institution which was to grow to legendary proportions. Eighteen months later, as the great new Metropolitan Tabernacle was opened, the class was attracting more than fifty young women. And still the numbers grew: fifty increased to eighty, and as the attendance climbed, a spirit of earnest prayer gripped the class which had caught its leader’s vision for reaching the unchurched women and girls of London.

Not surprisingly, therefore, the numbers continued to multiply. Eighty became one hundred, which in turn swelled to three hundred. Members invited friends to join, until the problem of space became acute. The only room in the Tabernacle large enough to accommodate such numbers was the Lecture Room currently being used by the main Sunday school. Mrs Bartlett’s vision and enthusiasm were irresistible and soon a reluctant Sunday school superintendent was persuaded to evacuate the Lecture Room. In 1865, six years after her tenuous acceptance of the responsibility, between seven and eight hundred women were meeting each Sunday afternoon at the Metropolitan Tabernacle. They ranged from girls in their late teens to grandmas of seventy years or more.

Mrs Bartlett led her ‘class’ single-handed, always addressing them herself. Gifted as a speaker, her messages were more in the nature of exhortations, for she insisted she was not preaching. In these exhortations, grounded on the great doctrinal truths of the faith, she urged Christian women to deeper devotion to Christ and to constant vigilance against sin. Looking on into the future, she would speak with anticipation of the joys laid up in heaven for those who persevered to the end. With tenderness and yet boldness she pointed out those sins to which most women are particularly prone. And always there was a note of urgency in her messages, for she regarded herself as ‘a dying woman’, and feared lest her opportunities to exhort and encourage her class should be cut short at any moment.

But it was in her appeals to the unconverted that Mrs Bartlett’s words took on an eloquence born of earnest desire. ‘Can you perish? Will you perish, my sister?’ she would enquire with pathos. One young woman who happened to enter the room as Mrs Bartlett spoke those very words was converted on the spot. Many conversions took place among those who attended this class, and even among those who came either out of curiosity or from unworthy motives. When six prostitutes arrived intending to disrupt proceedings, four were convicted of their sinful way of life and converted that very day, one of whom devoted her life to missionary work.

On another occasion an actress who had been persuaded to attend against her will left seemingly unimpressed. But she was back the following week. On the third visit she became convicted of her sins and as Mrs Bartlett addressed the class she cried out in des-pair, ‘Lost! Lost! Lost!’ Kneeling in prayer later with Mrs Bartlett, this young woman received an assurance of God’s forgiveness. An elderly woman who had hardened her mind against all Spurgeon’s earnest gospel appeals for more than two years entered the room as Mrs Bartlett was speaking. ‘Flee from the wrath to come, sister, flee from the wrath to come,’ the class leader was pleading. The words led to her instant conversion.

So great was the impact of the class each Sunday afternoon that Mrs Bartlett gave up all her time and energies to it. Often in pain, she found such service costly, but refused to heed those who cautioned her to take more rest. Her home, which Spurgeon fittingly called a ‘house of mercy’, was always open to women in spiritual distress. They saw in Mrs Bartlett a true friend and one who cared intensely for their needs and sorrows. Women confided freely in her and many were those who could tell how God had met them as they sat weeping on Mrs Bartlett’s settee. Numerous money-raising projects were organized by the class to support the Pastor’s College and every six months these women, many in straightened circumstances themselves, presented Spurgeon with a generous cheque worth over £5000 in today’s values.

A woman of intense force of character, Mrs Bartlett toiled on, her all-consuming object being to win these souls for Jesus Christ. Her one-month trial period had turned to fifteen years before her work was done. And it was estimated that over one thousand had been converted and joined the church as a direct result of her endeavours. ‘Few could resist the passionate utterances of this Bible teacher,’ wrote a friend. ‘Such earnestness, coupled with unwavering faith in God’s Word, could hardly fail to bring down heaven’s blessings. If you ask me the secret of this good woman’s success, I reply that it lies in her implicit reliance upon God’s promises and a strong assurance that he will do all that she believingly asks of him.’

And so in 1875 at the age of sixty-nine God called this noble and dedicated woman home. ‘My best deacon is a woman,’ Spurgeon used to say; and as he addressed her grieving class he spoke of the effectiveness of the leader they had lost: ‘Her unstaggering reliance upon the Saviour has led many of you to confide in him … I do not believe that any mother knew her children better than she knew the members of this class … her heart was large and her efforts incessant.’

Such a woman deserves to be still remembered by the Christian church. Words on her gravestone, chosen by Spurgeon, continue to bear silent witness to her worth. ‘She was indeed a mother in Israel. Often did she say, “Keep near the cross, my sister.”‘