‘Malden, his birthplace. The Ocean, his sepulchre. Converted Burmans, and the Burman Bible, his monument. His record is on high’.

So runs an inscription in the Baptist meeting-house in Malden, Massachusetts. It commemorates the life and work of Adoniram Judson Jr (1788-1850), eldest son of Adoniram Judson (1752-1826), a Congregationalist minister, and his wife Abigail (1759-1842).

State of shock

A precocious child, Adoniram was reading at the age of three and eventually went on to graduate from Providence College (now Brown University) in 1807 with the highest possible honours.

But university life placed a terrible strain on his beliefs, and he rejected his parents’ Christianity for the rationalistic thinking of the Enlightenment. At the time of his conversion in the autumn of 1808, he was part of a theatrical troupe living, in his own words, ‘a reckless, vagabond life’.

All of this changed when Judson spent a night at a country inn not far from Sheffield, Massachusetts. He found himself in a room next to that of a dying man. All through the night he could hear the man groaning. Finally he drifted off to sleep.

When he awoke in the morning the innkeeper told him that the man had died. ‘Do you know who he was?’ asked Adoniram. He was devastated when he heard the surname of one of his closest companions in unbelief and infidelity, Jacob Eames.

He passed the next few hours in a state of shock. He decided to give up his wayward life and, like the prodigal son, he headed home, chastened and on his way to genuine faith and repentance.

A call to the ministry

His conversion was also a call to ministry. He entered Andover Theological Seminary to begin training for a life of service. By February 1810 he knew he was called to be a missionary.

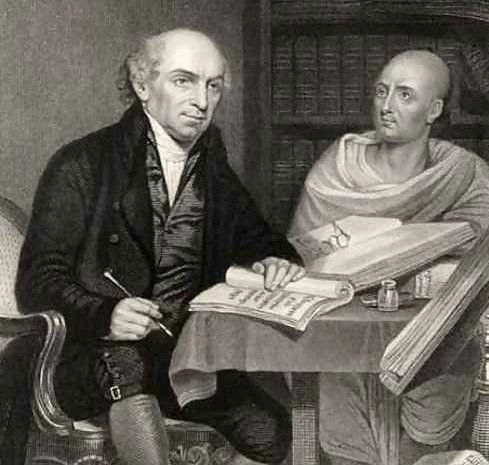

Less than twenty years earlier, a small circle of English Calvinistic Baptists had formed the missionary society that sent William Carey (1761-1834) to India in 1793. Carey’s example was the catalyst for the formation of a host of like endeavours among British Evangelicals on both sides of the Atlantic.

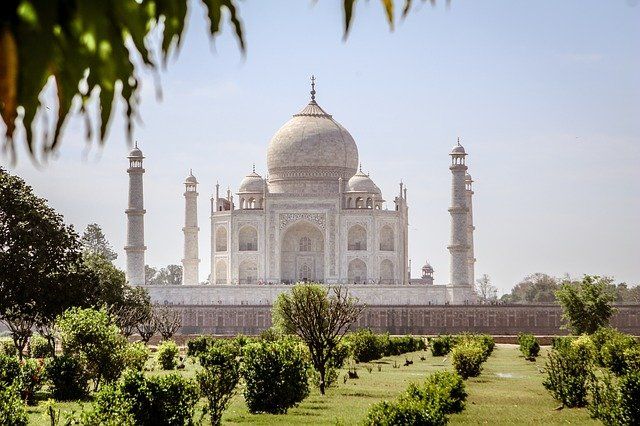

Among those influenced by Carey was the Anglican minister Claudius Buchanan (1766-1815), who had been mentored by John Newton (1725-1807) and Charles Simeon (1759-1836). Buchanan was for a time vice-provost of the College of Fort William in Calcutta, where Carey also taught.

When he returned to England in 1808, Buchanan sought to bring the missionary cause before the British public. Most notably, his sermon The Star in the East (1809) focused attention on the desperate spiritual plight of India.

Zeal for mission

Deeply influenced by this sermon, Judson — along with several other young men including Samuel Newell (1794-1821) and Luther Rice (1783-1836) — committed himself to serving the Lord overseas.

Their zeal was a major influence in the American Congregationalist churches forming the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. It was under the auspices of this body that Judson and the others were eventually sent out to India in February 1812.

Accompanying Judson was his bride, Ann Hasseltine (1789-1826), whom he had married exactly a week earlier and who would play a vital role in his ministry in Burma.

A change of sentiments

During the long voyage to the Indian sub-continent, Judson came to the conviction that his views on baptism were mistaken. As he wrote later, he now believed that ‘the immersion of a professing believer is the only Christian baptism’.

To Judson’s credit, he informed the American Board of his new perspective as soon as he arrived in India. His letter to the Board shines with Christian love, as Judson explains his change in sentiments. This change, he said, was the most distressing event ever to have befallen him, since it would prevent him from working hand in hand with men he counted as dear brethren.

Seeking out Carey, who was living a few miles away at Serampore, Judson explained what had taken place. So it was that Adoniram and Ann (who had arrived at similar views) were baptised by Carey’s colleague, William Ward (1769-1823), on 6 September 1812 in the Lall Bazar Church, Calcutta.

Led to Burma

When the Baptists in the United States learned of Judson’s change of view, they were moved to organise a missionary society in 1814, and so took the Judsons under their patronage.

However, the British East India Company — which had a mandate to rule British possessions in the sub-continent — was intensely hostile towards missionaries in India. The only way that the Serampore Trio — Carey, Ward and Joshua Marshman (1768-1837) — had been able to stay was by residing in the Danish colony of Serampore.

Within ten days of the Judsons’ arrival in India, they were ordered by the company to leave the country. In the providence of God they were ultimately led to Burma, reaching Rangoon on 13 July 1813.

Judson soon recognised the vital need to acquire complete facility in the Burmese language, so that he could translate the Scriptures and preach effectively to the Burmese. He gave himself unstintingly to this task.

It was not an easy language to learn, for its written form had no capitals, no word divisions and no sentence breaks, but Judson persevered. On 7 January 1814 he wrote to an American friend named Emerson: ‘My only object at present is to prosecute, in a still, quiet manner the study of the language trusting that for all the future, God will provide’. In time, he not only mastered Burmese, but did so with the elegance of a scholar.

Burmese Bible

On 31 January 1834 he completed the first draft of the Burmese Bible. It was a red-letter day in his life. As he wrote: ‘I have dedicated it to his [i.e. God’s] glory. May he make his own inspired word, now complete in the Burman tongue, the grand instrument of filling all Burma with songs of praise to our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ’.

Judson, though, was not completely happy with this first attempt and immediately began to revise it. It was not until 1840 that he was satisfied, and the entire Burmese Bible was published in a quarto edition, something he regarded as his major literary accomplishment.

His method in translating was, in his own words, ‘slow and sure’. He ardently desired that whatever he did in translating the inspired Scriptures was well done. His major nineteenth-century biographer Francis Wayland (1796-1865) noted that Judson deserves to be placed alongside John Wycliffe (c.1330-1384) and Martin Luther (1483-1546) for the solidity and excellence of his translation work.

Trials

This monumental task of translation was done against the backdrop of significant trials such as health problems; a war between Burma and Great Britain that led to Adoniram’s horrific incarceration by the Burmese as a spy from 1824 to 1826; the death of his first wife Ann in 1826; and the loss of their only living child, Maria (1825-1827), six months later.

Eight years later Judson married Sarah Boardman (1803-1845), a missionary widow. They had eight children, of whom three died in infancy. After Sarah died, Judson’s third wife was Emily Chubbock (1817-1854), whom he met on his only real furlough, a return to the United States in 1845-1846. He had asked Emily to write the biography of his second wife Sarah, and within a month proposed to her.

Back in the United States

By this time Adoniram was a living legend, a paradigm of missionary service. He appeared on public platforms in most of the major cities in the eastern USA, though often he could barely speak above what his son Edward described as ‘a husky whisper’. This, however, only added to the mystique surrounding him.

Some in his audiences found him a great disappointment. They expected to hear of his adventures, but he spoke rather of the cross and ‘pleasing Jesus’. This was the great motif of his life.

As he told one missionary gathering: ‘If any of you enter the gospel ministry in this or other lands, let not your object be so much to “do your duty”, or even to “save souls”, though these should have a place in your motives, as to please the Lord Jesus. Let this be your ruling motive in all that you do’.

He and Emily returned to Burma in 1846 where, over the next three years, he completed his final major literary project, a Burmese-English dictionary. In 1849, the same year that this work appeared, Adoniram fell ill with a severe cough that issued in dysentery and congestive fever.

Told that his one chance of survival was a long sea voyage, he left Emily and his family on 3 April 1850 on board a French barque. But he died on 12 April, and had to be buried at sea.

It was nearly four months before Emily learned of his death. She returned to the United States the following year and was an enormous help to Francis Wayland as he wrote the authoritative two-volume biography of the great American missionary.

His legacy

Judson’s legacy was vast. There was the church in Burma, firmly planted on the Scriptures he had translated. There was his model of missionary heroism and courage, a major source of inspiration for American missionary endeavour throughout the nineteenth century. His identification of Bible translation as a primary task of missions also proved to have long-lasting influence.

But above all, the heart of his missionary endeavour was his Pauline passion to please his Saviour (see 2 Corinthians 5:9). This is something we need to recover in our own day. As he said during his 1845-1846 tour of the United States:

‘Some one asked me, not long ago, whether faith or loveinfluenced me most in going to the heathen. I thought of it a while, and at length concluded that there was in me but little of either.

‘But in thinking of what did influence me, I remembered a time, out in the woods back of Andover Seminary, when I was almost disheartened. Everything looked dark. No one had gone out from this country. The way was not open. The field was far distant, and in an unhealthy climate. I knew not what to do. All at once that “last command” [of Matthew 28:19-20] seemed to come to my heart directly from heaven. I could doubt no longer, but determined on the spot to obey it at all hazards, for the sake of pleasing the Lord Jesus Christ’.