Is there a difference between how a congregation deals with offences and how individuals should handle forgiveness? Yes, there is.

When Ben left his wife to move in with the choir director, their church was thrown into turmoil. Repeated attempts to urge Ben to return to his wife were rebuffed. In a sombre business meeting the pastor tearfully recommended that Ben and the choir director, Gwendeline, be stricken from the rolls.

Decisive action

Some agreed. A vocal minority urged the congregation to exercise compassion by giving them more time to repent. Others responded that, by delaying action, they would be confirming them in their sin. Some lamented the lowering of the standards that they perceived had led to this crisis. They worried openly about the fallout among their young people.

Eventually, a vote was taken and both the offenders were removed from the church roll. A visit would be scheduled and a letter sent to explain the church’s action, adding that the door of repentance was always open.

Individual Christians are called to demonstrate revolutionary grace. As churches we must exude the same radical grace but, at times, this has to be balanced by actions of apparent severity. Failure to distinguish between our responsibilities as individuals and the duties of a local church body creates confusion. This confusion, in turn, damages the church’s moral climate, by hampering its ability to deal decisively with sin.

Paradox

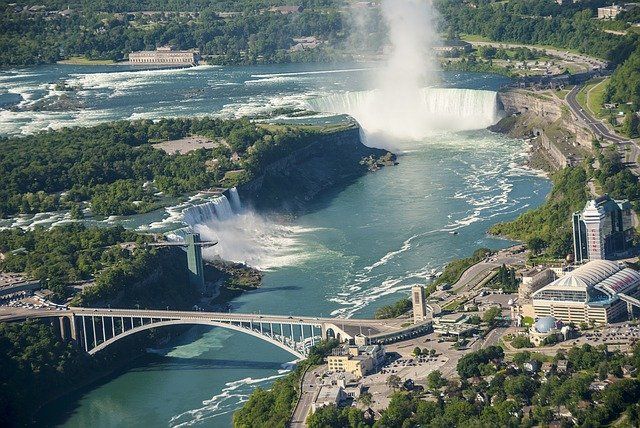

Without decisive action the church’s light grows dim. Balancing personal and congregational responsibilities can often seem like walking across the Niagara Gorge on a tightrope. Let me illustrate this distinction on several levels.

God has delegated responsibility to uphold justice in society to human governments. We expect our policemen to enforce the law. But we brand as ‘vigilantes’ citizens who take the law into their own hands.

We depend on our courts to mete out justice. In my view, the courts should even administer the death penalty where appropriate, as a just punishment and a valid deterrent for capital crimes. You may very well differ with me here. But I believe that to flounder over this issue is to fail to show compassion for society as a whole.

Or consider the question of war, another matter over which Christians differ sincerely. In my opinion, a country must protect its citizens from attack and engage in just wars. On the other hand, in our day-to-day relationships, when someone ‘smites us on one cheek’ we are to ‘turn the other cheek’.

The distinction between corporal and individual approaches to forgiveness reflects this paradox. On a personal level, we must show a willingness to extend unlimited forgiveness. On a church level, Christ commands us to discipline the unrepentant by treating them ‘as you would a pagan or tax collector’ (Matthew 18:17).

Four steps

In Matthew 18, Christ outlines the four-step approach a congregation is to take in seeking the recovery of a sinning member. Suppose a brother at fault rejects the efforts of one person, who privately strives to lead him to repentance. When he further rejects the entreaties of one or two more, and finally he even rejects the urging of the whole church, discipline is required.

This is no well-oiled, four-step way of dealing quickly with sin. Great patience, agonising prayer, tearful entreaties, and loving discussions may be involved. But when all efforts fail, Christ commands us to excommunicate unrepentant members (Matthew 18:17).

How can this be? We answer that God is the judge of all the earth. He has delegated authority to the church to act, within its own sphere, as his representative on earth. ‘Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven’ (Matthew 18:18). Local churches must exercise discipline because God has made them responsible to demonstrate that sin has consequences. Without maintaining high standards in the church, its credibility as a witness to the Holy God is compromised.

Restoration is the aim

In the church, no less than in society, justice delayed is justice compromised. Peter acted decisively in the matter of Ananias’ and Sapphira’s sin (Acts 5:1-11). Paul rebuked the Corinthian church for delaying church discipline (1 Corinthians 5:1-2). But when the discipline achieved its intended end, he again rebuked them, this time for delaying the reinstatement of the repentant person (2 Corinthians 2:6-8).

On a personal level, however, none of us possess the corporate authority of the church to exercise discipline. We should be careful not to pre-judge or shun those with whom we have a dispute. If we cut ourselves off from certain believers, in a case where the church as a whole has not taken action, we sin presumptuously by acting as if we were the judge. Even in cases of clear sin in others, we must walk a fine line that avoids encouraging the unrepentant in their rebellion but gently points to the way of repentance. Restoration must always be our aim (Galatians 6:1).