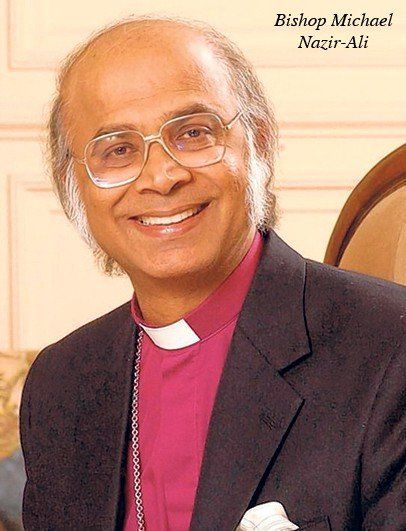

Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali was the 106th bishop of Rochester, until his resignation in 2009. He is now president of the Oxford Centre for Training, Research, Advocacy and Dialogue (OXTRAD). Before Sheila Marshall’s interview, for ET, of Bishop Michael, he casually remarked how four trees had just fallen in his garden, barely missing his house. He then proceeded to speak about his clear sense of God’s purpose for his life, amid all the challenges.

SM: What lessons from your Christian life prepared you for becoming bishop?

BM: I think our lives are always a preparation for what God wants us to do. Before I became Bishop of Rochester, I had Christian mentors who brought me to personal faith and gave me a model for mission. My ministry in the Middle East and Pakistan with the Church Mission Society (CMS) gave me a sense of the worldwide church. I was a bishop in Pakistan before I became the general secretary of the CMS.

SM: What helped your decision to resign to serve the persecuted church?

BM: Leaders in persecuted churches, both Anglican and otherwise, had been asking, ‘Help us to develop our leadership’. The leadership suffers first, because leadership is exiled, imprisoned or killed.

But you need particular qualifications such as language and culture for this role, which I had because of my Christian path. I tried to be involved when I was at Rochester, but increasingly saw that the role needed my full attention. When you begin something, you can’t predict what will happen. So that was the trigger.

SM: Can you recall an experience that didn’t quite make sense at the time but later helped your vocation?

BM: One example was my chairmanship of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority’s Ethics and Law Committee. I had to grapple with the moral and spiritual implications of developments in science.

When I was leaving, someone said, ‘You’ve never been comfortable here, Bishop, have you?’ I said, ‘Well no, but I didn’t come here to be comfortable’.

It gave me a grasp of the issues connected to the earliest stages of life, the human person and what Christians should say about them, in a way I could only have had from serving on such a committee.

SM: How has your vocation changed from your early days of ministry?

BM: My vocation has included teaching in a university, a college and a seminary. It has also involved being in a parish or working with a mission agency like CMS. It’s now about developing leadership in the persecuted church and talking to governments about fundamental freedoms for their people.

I also talk to people of other faiths, about freedom of belief and expression, because the freedom of Christians and others will, to some extent, hinge on what these leaders say and teach. What I hadn’t expected to do so much of, is to argue for freedom of conscience of Christians in the UK.

SM: How does your faith affect how you deal with the challenges?

BM: We have had threats to myself and my family on several occasions. That certainly leads to the deepening of faith. I would say that, without such experiences of suffering and brokenness, ministry doesn’t really become effective. Prayer also becomes very real in those situations. You become dependent on God because there is nothing else to fall back on.

I think, because I have had these experiences, I am able to minister with some credibility amongst the people that I do these days.

SM: You engage in debates with Islam, with governing authorities and with society. How does your faith inform you how to treat those who disagree with you?

BM: I continually meet people with whom I disagree strongly about belief and other things, such as freedom of expression. I like informed debate, so I expect people to do their homework on what I believe, and I research what they believe.

St John’s Gospel says that the eternal Word, incarnate in Jesus Christ, illumines us all, so we must assume that people are searching for truth. St Paul debating with the Greeks in Athens is one example of the mission of the church.

We need to have a proper knowledge of and respect for other people’s beliefs. Only then we can take them to the teaching of the gospel. But sometimes falsehood must be resisted, because it damages people, society and human relationships. But there is never any call to treat people with disrespect.

SM: What builds your faith?

BM: Worship, prayer and reading the Bible. I was reading the 10 Commandments this morning and was thinking about the idea of justice. Justice, irrespective of who a person is, is a principle from the Bible. So, the more you’re grounded in your faith, the more you understand what the Christian faith has given to the world.

SM: What else encourages your faith?

BM: Friends also help build faith. I know people in prison who are a radiant witness to the Christian faith. Last December, the BBC and I visited people who had been injured in a bomb blast at a church in Peshawar, Pakistan. The BBC crew commented that the peace manifested by those Christians, in the face of such hurt and pain, was amazing.

A father who had lost his daughter said that his Christian faith demanded that he should forgive the people responsible for her death. That’s the kind of thing that confirms and strengthens my faith.

SM: Among your various hobbies (including table tennis and, formerly, hockey and cricket) you write poetry in Persian and English. What have you written about recently?

BM: I still read Persian poetry, but I haven’t written any recently. The one thing I’ve hardly written is poetry in my own mother tongue, which is Urdu. I’ve tried, but it somehow didn’t come. I wrote this haiku [a Japanese form of poetry] in January:

The river frozen on its flow,

The birds silenced in their song,

The trees arrested in their growth,

Animals asleep in their holes,

And we confined to the quarters of our minds;

Christmas is over, winter is here!

© Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali