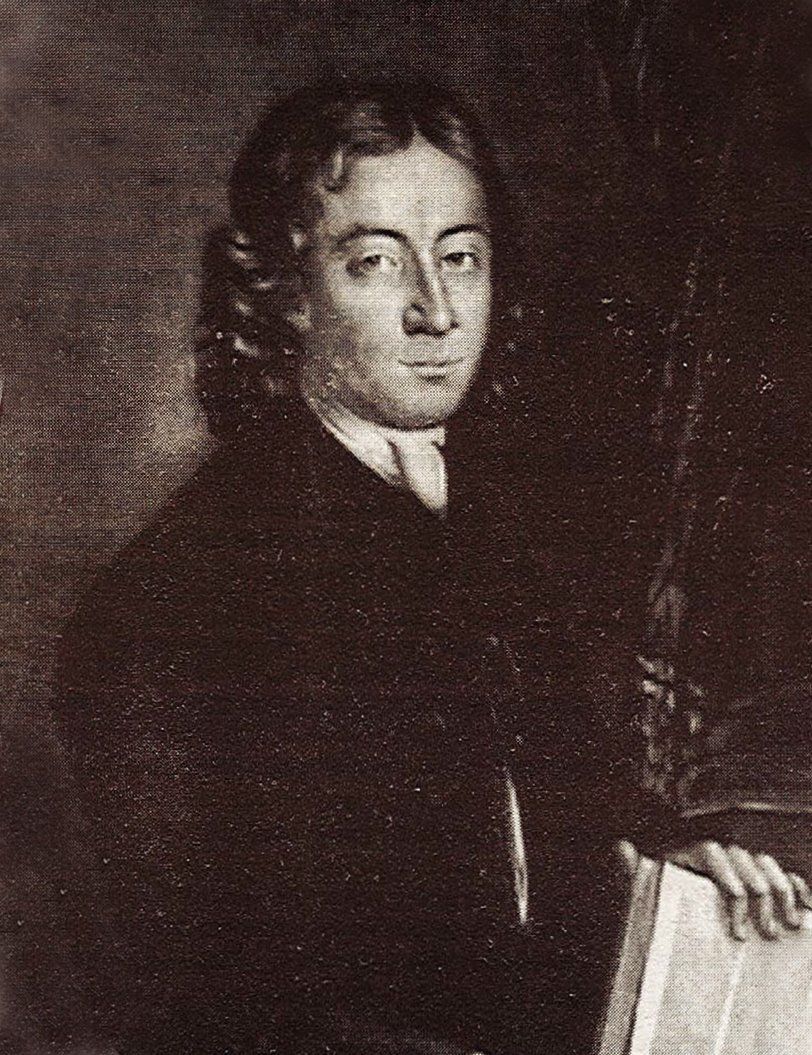

John Cennick is one of the lesser-known figures of the eighteenth-century Awakening. He was born on 12 December 1718, at Reading. His parents were attached to the Anglican Church. His mother instructed him in the faith and ensured he was regular at church. He says she ‘would not suffer me to play on the Lord’s day, but confined me to read or say hymns all day long with my sisters. This I then counted the worst of bondage and indeed cruelty.’ When he was a young boy, he visited a dying Christian aunt. Her words of assurance on her deathbed were impressed upon him and he often meditated on them.

In his Journal he recounts that, as a boy, he was obstinate and sinned continually with lies, Sabbath-breaking, stealing from school-fellows and disobedience to parents. He dreaded going to bed in case he would drop into hell before the next morning. Praying before bed he would promise God that he would be good the next day, but never succeeded!

When he was thirteen he went to London to seek an apprenticeship, but, despite several attempts, he failed to obtain employment. When he was about fifteen his mother had a shop built for him, but he lacked business skills and finally contented himself with various types of private work. In his mid-teens, he says, ‘I delighted … in singing songs, talking of the heathen gods, of wars of Jews and Greeks, of Alexander the Great and in the cursed delusion of card playing, in seeing fights, in horse races, in dancing assemblies, revelling and walking with young company.’

Conviction

About Easter 1735 he experienced a period of deep conviction of sin. It was a time of great misery for him: ‘I felt at once an uncommon fear and dejection … through the strength of convictions and the fear of going to hell … I knew not any weight before like this.’ No amusement could lift the load. Getting away from the town for a walk in the country did no good, for even there ‘the terrors of the Lord came upon me, and the pains of hell took hold of me’. A light-hearted companion eased the burden, but only for a time, for when they separated, the burden returned. ‘Whoever I met I envied their happiness. Whatever I heard grieved me; whatever I said or did so troubled me, that I repented that I stirred or broke silence. If I laughed at any thing my heart smote me immediately; and if the occasion was a foolish jest or lie, I thought, alas! I helped not only to ruin my own soul, but the souls of others too.’

He gave up worldly amusements, he even considered going into a monastery to get peace of mind, but it was all to no avail. Often he would be haunted in bed at night by confused thoughts. He tried exercise, eating and medicine, but all proved useless. He confesses that although he was convicted of sin he had no power over sin: ‘I committed it continually, though not in the eyes of the world. My chief sins were pride, murmuring against God, blasphemy, disobedience, and evil concupiscence; sometimes I strove against them, but finding myself always conquered I concluded there was no help.’ In church his mind wandered. It seemed to him that his worship was a mockery of God. At one point he left off praying for he considered the prayers of the wicked an abomination. The devil suggested to him that there was no God. He cried out, ‘Have I sinned more than all the sons of Adam? O that I had never been born.’

He was convinced that heaven was closed to him. He described these times: ‘I stood still and fixed my heavy eyes on the trees, walls or on the ground, amazed above measure, and often crying with a bitter cry, “What must I do to be saved?”‘ He thought of going to the country to be a plough-boy, of even starving himself to death, but he could not get any peace. ‘I could not be thankful for any temporal blessings, because I thought myself so unsettled, and because no blessing satisfied my craving soul or made me wish to stay behind on earth a day … nor could meat, drink, or raiment give me any comfort; I only wanted to know if I had any part in Jesus.’

He tried mortification, eating only once a day and fasting from Friday breakfast until Sunday noon, when he had Communion, but it was no good: ‘No alms, or fasting, or prayers, or watchings could cover my naked soul from almighty wrath.’

This period of conviction lasted for about two years during which even Scripture brought him no comfort: ‘To me all beside the law and the judgements and their terrors were like a book sealed so that I could not read it (as I thought) to profit by it at all.’

Conversion

Around August 1737, finding his own efforts to obtain salvation were of no use, he says, ‘I began to resign myself to the disposal of God. I gave up my desires and remains of hope; being content to go down to hell … I found that I was willing on any terms to be saved, but was convinced I deserved hell and so bowed to the justice of God.’ He began to seek God for mercy. ‘I no longer said, Lord remember how innocent I lived … but pleaded the great oblation and sacrifice of Christ crucified, I entreated mercy for his sake alone: I knew my guilt, and was dumb before my God.’

He resolved to go to some lonely place on 7 September to wait on God. However on 6 September he had a bad day and was much dejected. He heard the bell of St Lawrence ringing for prayers and reluctantly he went to church. Graphically he describes his feelings, ‘I went out like some outcast into a foreign land; my heart was ready to burst, my soul was on the brink of hell … Had any met me my countenance would have betrayed me as well as my voice and tears.’

Entering the church building he fell on his knees aware of his sinful condition and that he was bound for hell. ‘It was as if the sword of the Lord was dividing asunder my joints and marrow, my soul and spirit,’ till near the end of the Psalms when he read ‘Great are the troubles of the righteous, but the Lord delivereth him out them all’ and ‘He that puts his trust in the Lord shall not be destitute’ (Psalm 34:19). ‘I had just room to think, “Who can be more destitute than me?”, when I was overwhelmed with joy and believed there was mercy. My heart danced for joy, and my dying soul revived! I no more groaned under the weight of sin. The fears of hell were taken away, and being sensible that Christ loved me, and died for me, I rejoiced in God my Saviour.’

Soon Satan returned to buffet him with doubts and he cried aloud for mercy, casting himself on God. A few days later, while still under temptation, on a dull day, suddenly the sun shone in the sky. Then the promise of God suggested to him, ‘”Thus shall the Sun of righteousness arise in thee.” I believed the promise, and found the love of God again shed abroad in my heart.’ He experienced peace from this time and assurance of salvation. Later he became an evangelist, joining the Moravians, and was greatly used by God in Britain and Ireland.

Lessons

1. The early religious training bore fruit in later life. How important is a godly home.

2. God allowed him to pass through a period of deep conviction of sin, bringing him to the place where he saw he deserved hell and his only hope was in the mercy of God. We need in our day to pray that the Lord would grant that lost souls will be brought to this true conviction of sin.

3. His conversion came during a normal church service, and not even through preaching, but through the reading of a psalm. We see how God uses ‘normal’ worship to bring people to himself. Too often we underestimate the importance of the normal church services.

4. In his conversion too we discover the sovereignty of God in salvation. It reminds us again – it is God who saves.