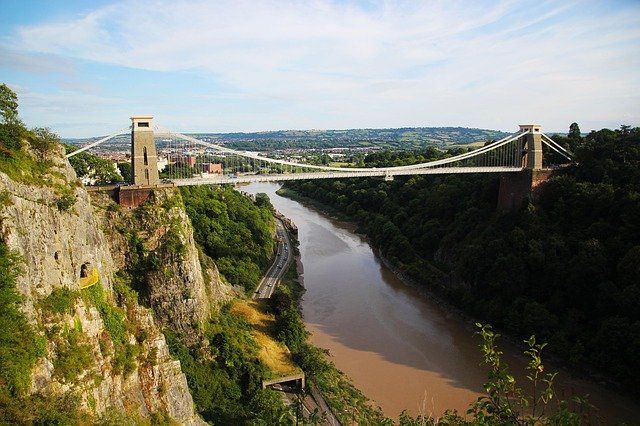

If you have ever watched the BBC’s Casualty series, you have seen George Müller’s orphan houses on Ashley Down in Bristol, where the series was filmed. They are impressive buildings, especially as no fund-raising for them was ever undertaken. During the course of his life, George Müller raised around £1,400,000 without ever asking anybody for one penny.

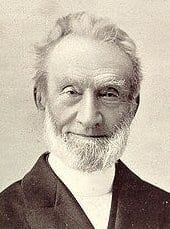

Born at Kroppenstädt in Prussia on 27 September 1805, he was an incorrigibly dishonest boy, given to theft and fraud from his earliest years. At the age of fourteen, George was at boarding school when, unknown to him, his mother became ill. While she lay dying he spent the weekend playing cards and getting drunk. He returned to school to find his father waiting to take him home for the funeral. After this he resolved to reform.

However, he found himself utterly powerless to mend his ways, and at the age of sixteen he spent three weeks in jail for dishonesty until his father paid his debts and brought him home for a good beating. Again he determined to improve, yet to no avail. There was scarcely a sin that he did not indulge in. At the age of nineteen he entered Halle University. His life of dissipation led to illness, putting his career in jeopardy, and he became very depressed.

Mercy from God

In 1825 he was invited to a home Bible-study group, where he first witnessed a man kneeling to pray. Müller knew that, for all his learning, he could not have prayed so well as this illiterate tradesman, and he felt an inexplicable joy, which he saw as a great mercy from God. From then onwards he became an openly professing Christian and began to change, the love and grace of Christ achieving what his upbringing and all his efforts to improve had failed to do. George Müller’s father disapproved of his new faith, so George supported himself through university, as it seemed unfair to take his father’s money while rejecting his career plan. By now he was determined to become a missionary. He subjected this desire to a long period of prayer and fasting, and began to learn the persistent waiting on God which was to become the characteristic feature of his life.

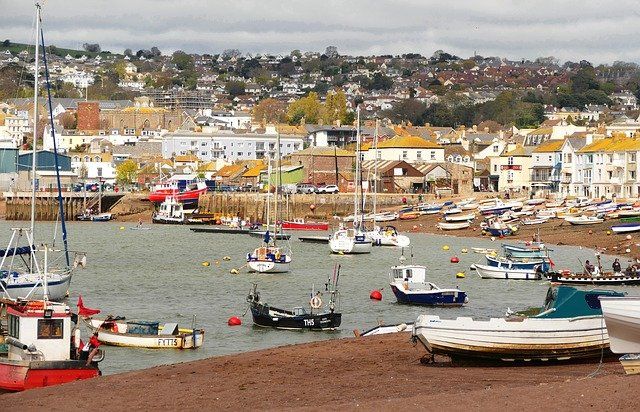

God provided employment, accommodation and more money than he needed. In 1829 he came to London to study Hebrew under the auspices of a mission to Jewish people. Falling ill, he went to convalesce at Teignmouth, where he met Henry Craik who was to become his partner in the orphanages. Here he learnt to meditate on the Scriptures, and he later said that the effect of this was like a second conversion. He began to devote his life more and more to prayer, finding great joy in his fellowship with God. After leaving the mission he took up the pastorate of Ebenezer Chapel, Teignmouth.

Faith as ‘a good coin’

In 1830 he married Mary Groves, and the marriage was blissfully happy. They had no wedding reception or honeymoon but returned straight home and the next day resumed their work for the Lord. Three weeks later they decided to relinquish George’s salary, which consisted of pew rents, and resolved never again to ask for money but to make their requests known only to God. By the end of the first year they had received gifts of £131 18s 1d, plus around £20 worth in kind – far more than his salary would have been.

Müller repeatedly warned against presumption, but said that faith, ‘as a good coin’, would be honoured by God. He adhered to this principle scrupulously. Where God gave him faith he would act with great boldness. Once he undertook three preaching engagements against medical advice while seriously ill. He told the doctor that this would have been great presumption had not the Lord given him faith in the matter. Within four days he was completely recovered. However, years later, when his son Elijah was dying of pneumonia, he had no sense of faith for the baby’s healing. He therefore prayed only that, if he were to die, the end would come quickly with minimal suffering, and that Mary would be given strength to bear the loss. Both these prayers God answered.

Orphanage

In May 1832 the Müllers joined Henry Craik in Bristol. George Müller took up the pastorate of Bethesda Chapel and in 1834 he founded the Scriptural Knowledge Institution for Home and Abroad. The purpose of this organization was to promote Christian truth through education, Bible and tract distribution, and direct grants to freelance missionaries. Later that year he began to pray about an orphanage project. He prayed specifically for premises, staff and £1,000. By 3 February 1836 the orphanage was ready to open, but not a single child was sent to him. He realized that the one thing he had not prayed for was children! He began to pray for them to come, and by 18 May he had thirty orphaned girls in his care.

Müller wanted to rescue orphans who would otherwise go to the workhouse or live on the streets, and provide them with care, education and training. But his supreme motivation was the desire to give visible proof of a living God who answers prayer.

The work mushroomed, and by 1844 there were four orphan houses, catering now for boys as well as girls. No appeals for funds were ever made, yet all their needs were met. The presence of so many children in a narrow city street began to be problematic, and by 1870 five orphan houses, costing a total of £50,000, had been built on Ashley Down. At the time of Müller’s death, 2,050 children were in residence, and he cared for a total of 10,000 in his lifetime. In addition, there were 189 missionaries to be supported, 100 schools with 9000 pupils, 4,000,000 tracts and tens of thousands of Bibles to be sent out each year.

Miraculous provision

Stories abound of God’s miraculous provision. One breakfast time there was no food. Müller confidently said grace. Immediately there was a knock at the door. It was the local baker who had woken in the night with a feeling that God was telling him the orphans had no bread. So he had risen at 2.00am to bake some for them. Shortly after this came another knock at the door. The milkman’s wagon had broken down outside the orphanage. He asked if he could give them his milk, so as to be able to empty and repair his wagon.

Although the orphans knew that everything they had was provided by God, they were unaware that they often lived from hand to mouth. As a result, they had no sense of financial insecurity. Charles Dickens heard a rumour that George Müller’s orphans were ill-kempt and starving, and decided to investigate. Müller gave his keys to an employee with instructions that Dickens be allowed to look over any of the orphan houses. He went away entirely satisfied. The children were indeed well cared for by the standards of the day, though their routine and diet would seem monotonous today. Their state of health compared very favourably with the general population, they had plenty of toys, and the vast majority looked back on their childhood in the orphanages as a period of great happiness. All of them went into secure employment, and many of them trusted Christ during the years of their upbringing.

Meticulous accounts

In 1870 Mary Müller died, and eighteen months later George married Susannah Grace Sangar. She lacked Mary’s talent for mothering the orphans, but was able to accompany her husband on preaching tours all over the world – something which he could never have undertaken alone. In seventeen years they covered 200,000 miles, preaching and teaching. He records that he was in far better health in his eighties, after a lifetime of serving God, than he had been in his twenties as a result of his dissolute youth.

Müller always kept meticulous accounts. From 1834 until his death in 1898, he received gifts for the orphans totalling £988,829 0s 10 1/2d, and for the other work, £392,341 18s 7d, without ever making his needs known or appealing for money. From 1874 – 1885 he and Susannah received £30,000 in gifts for their own use, of which they gave away more than £27,000.

On 10 March 1898, having outlived both his wives and both his children, George Müller died at the age of ninety-two, leaving the orphanages in the care of his son-in-law who had been director for some time. Today the work goes on, though in a different form. There are no residential orphan homes now, but youth and school work is carried on, as well as projects to help families. There are self-esteem and bereavement groups for children, anger management courses, and help in the home for parents who need it. The Scriptural Knowledge Institution continues to support Christian work at home and abroad, and there are homes for elderly people. One thing has not changed, though. One hundred years after the death of its founder, the George Müller Foundation still makes no appeals for funds.