This book is Bornstein’s account of his experience of the Holocaust. He was first incarcerated in September 1938 (aged 15) and was finally liberated by American soldiers in April 1945.

It is a harrowing account of suffering, opening with a family tree revealing just five survivors from over 60 original members. Bornstein shows the idyllic, loving closeness of a family life centred on regular family worship shattered when Germany invaded Poland.

From then on, life would never be the same. Like me, you may be unfamiliar with names like Grunheide, Markstadt, Funfteichen, Grossrosen, Flossenburg, Leonberg and Muhldorf. But, as you read the accounts of these places, you will see how each descends further into depravity and suffering, leaving an indelible mark of sadness. Despite this, there are moments of human kindness from both fellow sufferers and guards.

The labour camps were designed to ‘destroy the soul’ through relentless roll calls (involving standing for hours in freezing temperatures) and forced labour. Work was done building autobahns and munitions factories. Always fed below starvation levels, interns were gradually ground down to the point of losing the will to live.

Still a teenager, Bornstein recalls that: ‘My belief in God and faith in people and their moral code had long ago been broken. If ever I could breathe in freedom again I believed I could no longer respect any law, nor recognise any God or religion. From the moment my parents had started on the road to Auschwitz, love, compassion, goodness and justice were words that no longer held any meaning or significance for me’ (p.69).

Many Jewish interns tried to maintain their rituals and festivals. During one Passover, Bornstein was invited to make up the quorum, during which we read a moving description of how he and others drew strength in their weakness as they remembered Israelite suffering under Pharaoh.

The context is always immense personal suffering. In Grossrosen, his close friends were murdered — companions who had encouraged one another to ‘keep going’. He writes, ‘Those were my last hours in Grossrosen. I lost my best friends. Images of unforgettable horrors were etched forever into my soul. Broken, filled with painful, insane, tortured thoughts, I slowly marched out of the camp gate. Without thinking, I took my place in the column as we marched five abreast’ (p.147).

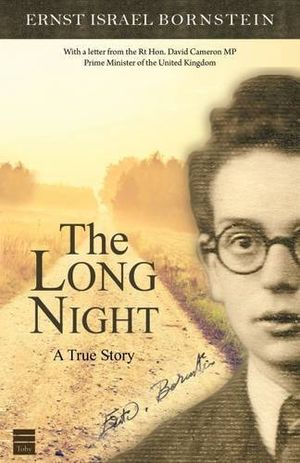

The penultimate camp, Flossenburg, is the hardest to read. The train journey in coal wagons took four days with no food or water. Hundreds died, Bornstein losing his beloved Uncle Leon and his most treasured possessions — his spectacles and shoes.

A few years ago I visited Auschwitz and thought how important it was to have done so; we must not forget the unspeakable wickedness of the Holocaust. So why read this book? My response is that it brings these horrors to a personal level. Ernst Bornstein writes almost ‘matter of factually’, without overstating his experiences in an emotional or extreme way. It carries a weight and authority from which we can learn much.

Read this book. It is not easy going, but it is thought provoking and a reminder that we serve a God who, through the sin-bearing sufferings of Jesus Christ, will one day put all wrongs to right and make all things new.

Graham Hilton

Pewsey, Wilts