This month and next we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the birth on

15 October 1755 of Thomas Charles of Bala

In a narrow and lovely valley at the foot of Cadair Idris lies Castell y Bere — one of the castles of the Welsh princes of old. Nearby is the small hamlet of Llanfihangel-y-Pennant. Here at Tyn-y-ddol cottage, nine days before Christmas 1784, a daughter was born to Jacob and Mary Jones. She was named Mary and known in the district as ‘Mary Jacob’ (Jacob was her father’s first name).

Her parents were poor weavers who worked from dawn to dusk to make a living. Like most Welsh country folk at that time, they could not read or write. Before Mary reached her fifth birthday, her father died, and from then on she and her mother must have had a hard struggle to make ends meet.

Lantern

Mary’s parents trusted in Jesus Christ as their Saviour and sought to obey him as their Lord. They used to meet with other Christians, usually at Llechwedd in the same parish, which was the home of William Hugh, a Methodist preacher.

In those days such a group of believers was called a seiat (‘society’). The members of the seiat were few in number, poor, and persecuted for their faith. But they were very zealous, faithful in attending the meetings, earnest in prayer and upright in life.

We are told that Mary’s mother took the child with her to the evening meetings at Llechwedd. Often it would be a dark night and Mary would carry the lantern to light the lonely path.

It was unusual for children to attend the society meeting in those days, but Mary was allowed because she carried the lantern. No doubt those meetings helped her to become familiar with the Bible and its message.

Thomas Charles

Thomas Charles was an important man among the Welsh Methodists at that time. He was a preacher and lived at Bala. He was deeply concerned that the common people could not read. Some years before, Griffith Jones of Llanddowror had started schools to teach the people to read the Bible, but these had come to an end.

Thomas Charles decided to start similar schools. He had teachers who would move from one district to another, staying in each place for a few months before moving on. Because these schools moved from place to place they were called ‘circulating schools’. In these schools the poor would be taught to read the Bible and instructed in some of the great truths of the Christian faith.

When Mary Jones was about ten years old, Thomas Charles opened one of his circulating schools in Abergynolwyn, a village some two miles from Mary’s home. The teacher was John Ellis of Barmouth and, soon after, he started a Sunday school there as well. Mary attended the circulating school and before long she was able to read the Bible herself. She was also one of the most faithful at the Sunday school, it is said.

Costly

In those days Bibles were very scarce and very costly. There was no Bible in Mary’s home but they had one at Penybryniau Mawr, a farmhouse about two miles away. There it lay on the table in the parlour.

‘Please, may I read your Bible?’ Mary asked the farmer’s wife one day. ‘Of course, my girl,’ she replied, ‘come whenever you like.

Mary was delighted; so much so, that she would walk all the way to Penybryniau Mawr every week, rain or shine, to read the Bible and learn passages of it by heart.

But Mary’s dearest wish was to have a Bible of her own and she began to save. You needed a small fortune to buy a Bible in those days, and for years Mary carefully put aside every penny she received from neighbours for helping them.

At last, after long years of waiting, the day came when she had enough to buy a Bible of her own. But where could she get a copy?

White horse

One wet stormy Monday morning, when she was about fifteen, Mary was walking to Penybryniau Mawr as usual to read the Bible. The wind whipped at her clothes and low clouds scudded over the mountains. Coming towards her she saw a gentleman wearing a cloak and riding a white horse.

‘Where are you going, my girl, in this foul weather?’ he asked.

‘To Penybryniau Mawr, sir, to read the Bible’.

‘Why are you going so far to do that?’ he asked.

‘We have no Bible at home’, she replied, ‘and there is none nearer. I have been saving every penny for a long time now, and I think I have enough to buy my own Bible, but I don’t know where I can get one’.

Mary had met the very person who could help her. The man on horseback was Thomas Charles of Bala.

‘Well, as it happens’, he said, ‘I am expecting Welsh Bibles from London before long. If you bring your money to Bala, I will give you one’.

Mary felt she was walking on air that morning, despite the rain, and she eagerly looked forward to the day she could hold a Bible of her very own in her hand.

Disappointment

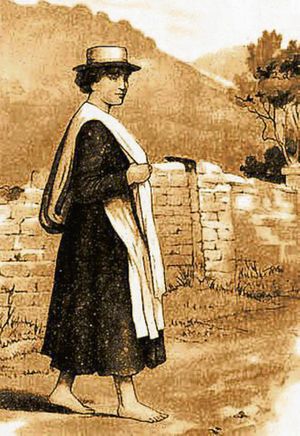

At last, the time came for her journey to Bala. It was a long way from Llanfihangel — twenty-five miles or more over a rough track. There were no wide, smooth roads in those days and she would have to walk every step of the way — most of the time barefoot, for poor people used to do this rather than wear out their clogs.

Early one fine morning in 1800 Mary set out on her long journey. Over her shoulder she carried a ‘wallet’ (a type of double bag). Her mother had carefully put the money for the Bible in one side of the ‘wallet’ with some bread and cheese, while the other side held her clogs.

She was so eager to reach Bala that she ran for much of the way, stopping to rest beside a clear stream to eat her lunch. At last, a glimpse of blue. Bala Lake was in sight and, before long, the town itself. She was almost there! Arriving at Thomas Charles’ house in the High Street, she knocked timidly at the door.

‘Is Mr Charles at home?’ asked Mary when the door opened, and she was shown to his study at the back of the house. Thomas Charles had not forgotten her but there was a disappointment in store.

‘I’m sorry, my girl,’ Mr Charles said, ‘but the Bibles have not arrived from London yet’.

Tears and joy

Mary burst into tears when she heard this. What was she to do now? Where could she stay in Bala until the Bibles came?

‘I will arrange for you to stay at the house of my former maidservant, Catrin Sion, who lives nearby’, said Mr Charles.

She stayed there two nights, and then the precious Bibles came. To her great joy she was given not one but three — and that for the price of one! No girl in all the world was happier than Mary! She ran most of the way back to Llanfihangel, the Bibles in one end of her ‘wallet’ and the clogs in the other.

The story goes that Mary composed a verse telling of her joy on that never-to-be-forgotten day. Here is a translation:

Yes, at last I have a Bible,

Homeward now I needs must go;

Every soul in Llanfihangel

I will teach its truths to know;

In its dear treasured pages

Love of God for man I see;

What a joy in my own Bible

To read of his great love for me.

Three Bibles

Two of Mary’s Bibles can still be seen today. One of them (her own) is in Cambridge University Library. A relative of her mother’s had one of the others and this is now in the National Library of Wales at Aberystwyth. Nobody knows what happened to the third.

Mary married a man called Thomas Jones and they worked as weavers all their lives, as did Mary’s parents before her. For most of their life together they lived in the village of -Bryn-crug, near Tywyn — not far from Llanfi-hangel–y-Pennant.

Thomas Jones was an elder in the Methodist chapel at Bryn-crug. They had a number of children, but most of them died young. One of their sons, John, went to America. Could he perhaps have taken the third Bible with him?

She spent her last years in a tiny cottage in Bryn-crug, old and blind and a widow. On a wintry day four days after Christmas 1864 she died, having just reached her eightieth birthday.

She was buried in the graveyard of Bethlehem Chapel, Bryn-crug, and her grave can still be seen there today. Mary Jones’ life was one of poverty and hardship yet she left a rich legacy, as we shall see next month.