Born in Rotterdam in 1747, John Vanderkemp1 was a disappointment to his parents. Outstandingly intelligent, the Dutch schoolboy had mastered sixteen European languages before graduating to Leyden University, where he began to study medicine.

The problem lay not in any indolence on John’s part, but in the boy’s total rejection of the faith and moral standards which as a child of the manse he had been taught from earliest days.

Tall, good-looking and bubbling with life, John found himself highly attractive to women, but also an easy dupe to those who used their charms to beguile him.

To his rejection of the Christian faith and his immoral lifestyle, John added the sin of hypocrisy, as he applied for and received full membership of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Little wonder that his parents grieved over him. Impatient of study, he soon gave up his medical career and joined the army.

Pangs of conscience

At the age of twenty-five, John Vanderkemp cast his eyes on a young married woman. Writing long afterwards he confessed: ‘I stole her from her husband and took her to Leyden where I lived publicly with her’.

But John was not without pangs of conscience. His manuscript account of his early days is blotted with tears as he records that, in his view, the pain he had caused hastened his father’s early death.

In a desperate attempt to make amends he sent the woman away, but as soon as his father died he received her back into his home once more. Soon a daughter was born.

The birth of his daughter weighed Vanderkemp down with a sense of guilt. For no fault of her own, this child would go through life under the shadow of her parents’ wrongdoing.

After mutual discussion, John decided to separate from his mistress, but the child was to remain with him. For her sake he would occasionally attend a church service.

Once he heard a sermon on the text ‘Oh when wilt thou come unto me?’2 The message was soon forgotten but these words of Scripture evoked a nameless desire in the soul of the dissolute man.

It was a desire he could not erase, day or night, however dark and unworthy his conduct became.

Marriage

The 18th-century equivalent of night clubs proved an irresistible magnet to Vanderkemp, and many illicit relationships contracted there marred his life.

But one day he noticed a simply dressed country girl passing his front door. Had he seen her before? He was not sure.

Hurrying out, the dashing army officer introduced himself. Glad enough for someone to show interest in her, Christina told John of her unhappy home where her stepmother made her life unbearable.

With typical largesse and impetuosity, John arranged for other accommodation for the twenty-three-year-old, and even began to talk to her of marriage. Here he had a surprise coming to him.

For Christina was not like the flighty girls he usually met. She would only marry him on three conditions. Firstly, that he repented of his sins; secondly, that he gain her father’s permission; and thirdly, that John’s daughter, now seven, was happy with her as a stepmother.

Searching questions

After his marriage to Christina, Vanderkemp decided to relinquish his commission in the army and took a long honeymoon in England. But what could he do now?

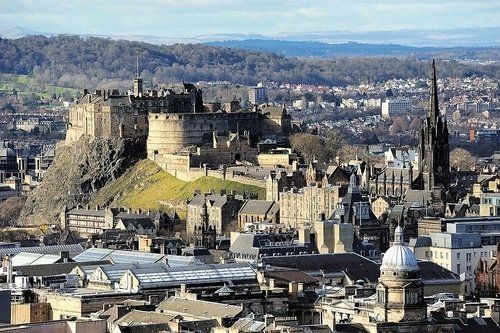

He would return to his medical career, discarded so many years ago. Edinburgh appealed to him and here he gained a place to complete his studies.

With a love of solitude, Vanderkemp often climbed up to Arthur’s Seat, from which rocky vantage point he could gaze on the wide vistas across Edinburgh.

But as he gazed, his mind turned not to the God of creation but strayed into a maze of Greek philosophical notions and pantheistic concepts.

After two years of study in Edinburgh, the Dutchman passed all his examinations and, returning to Holland with his family, settled in Middleburg to begin his medical practice.

Christina was anxious to become a church member and would ask her husband searching questions about Christian doctrine ‘ questions that forced John to turn his mind back to thoughts long since spurned.

Spiritual crossroad

He also felt the responsibilities of his ten-year-old daughter. Did he really wish her to imbibe all her father’s sceptical ideas? Dutifully John began to instruct the child in the Scriptures.

But the more he studied the more unbelieving he became. How could such a rationalist as Vanderkemp accept Christ’s miraculous interventions with the course of nature ‘ stilling a storm; reversing lifelong deformities; even raising the dead?

He could not. He must resign his church membership. But what effect would that have on Christina and his daughter?

Facing a spiritual crossroad, Vanderkemp decided he must live a life of virtue as noble as that of any Christian. But he failed again and yet again.

His sins cried out for punishment, yet if he accepted the forgiveness offered in the gospel, he felt he would only make it an excuse for more sinning.

‘Oh when wilt thou come unto me?’ The words of that text from so long ago still echoed in his mind.

‘Oh chastise me as long and as heavily as may be necessary to make sin unbearable to me’, was now his urgent prayer.

Alone

During this time of confusion, Vanderkemp decided to move his family to Dordrecht where he hoped the climate would suit him better.

One calm June day in 1791 John took Christina and his daughter, now an attractive teenager, on a sailing trip up the River Maas that flowed nearby. After a pleasant trip, they turned homeward as the sun went in.

Dark and threatening clouds began to gather. Then the rain lashed down and a gale sprang up, tossing the little craft about like a cork. Quite suddenly, a whirlwind flung the boat upside down and all three were pitched into the rough water.

It was the last John Vanderkemp saw of his daughter. Unable to swim himself, he yet struggled valiantly to keep hold of Christina. Twice he dragged her up from below the surface, trying to cling to the upturned boat.

Then he lost his grip of her once more. Exhausted he could only grasp hold of the keel and hope that someone would come to his rescue before he too succumbed to the fury of the waves.

At last, as the storm abated, the sole survivor of the tragedy was sighted by a passer-by and a rescue was mounted.

Resting in Jesus

Desolate, John Vanderkemp returned home alone ‘ all he had loved now gone. The following Sunday he was to be found attending a communion service. And, far from rejecting him, here God met the bereaved man.

Face to face with the One whom he had long despised, John bowed his proud head and owned that God had a right to take his wife and child. More than this, he was brought to the place where he could give them up freely.

Then he went a step further: ‘I give myself with all that I have entirely to you whose power and love I now feel’.

He realised at that moment that ‘the only religion that satisfies the soul consists of resting in Jesus’. Bereft of everything, John Vanderkemp now possessed all.

He ate the bread and drank the wine with a believing heart. That was a never-to-be-forgotten communion service.

Light without shadows

With the close of the eighteenth century came a heightened awareness of the needs of the unevangelised nations of the world.

Carey had sailed for India in 1792, the year after Christina’s death, and in 1795 the London Missionary Society was formed with thirty young men and women sailing to the far-off South Sea Islands.

Fired with a similar zeal Vanderkemp now used his influence to form the Missionary Society of the Netherlands in 1797. More than this, he volunteered himself to sail to South Africa with the London Missionary Society in 1798.

Settling among the Kaffir people far inland where few white men had yet ventured, Vanderkemp built himself a frail hut, scarcely able to keep him dry at night or save him from prowling animals.

Here he taught a people sunk in superstition and spiritual darkness to know the God he too had once despised. When the Kaffir king resolved that the missionary must die, Vanderkemp moved within the borders of Cape Colony, where he worked among the exploited and deprived indigenous black population.

He established a mission station, school and church which he named Bethelsdorf. Though he had also longed to reach the people of Madagascar, God had other thoughts and in 1811, at the age of sixty-four, Vanderkemp’s work was done.

‘What is the state of your mind?’ asked a friend anxiously. ‘All is well’, whispered the dying man. ‘Is it light or dark with you?’ persisted the friend. ‘Light’, came back the answer, as John Vanderkemp left the shadows of earth behind for ever.

Footnotes

1. Anglicised version of Johannes Van der Kemp

2. Psalm 101:2